Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

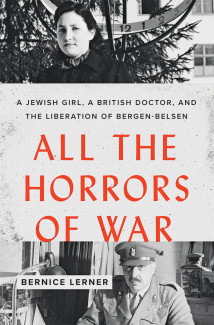

All the Horrors of War – Q&A with author Bernice Lerner

You wrote All the Horrors of War partly about your mother, and her narrative accounts are incredibly detailed – what did the interview process for these portions look like?

I have been asking my mother questions since I was a little girl, didn’t want to go to bed, and could stay up as long as I could keep her talking. Our conversations about her past continued through my teenage years (when I learned about her wartime experiences) and over subsequent decades. So I had organically acquired a framework, knew where she was during the war, and had heard many of her stories repeatedly. When I wondered about something specific I might include in the book, I might say, “I hate to take you back to this painful moment, but when you were on the death march (for example), can you recall what you were wearing?”

Can you describe some of the feelings and emotions you had to process – as a daughter, as a Jewish person, as a scholar – while you completed these interviews with your mother?

In order to write about my mother, I tried to envision the young girl she once was. Her dispositions and childhood circumstances made her a compelling protagonist, and I felt a mixture of sadness and pride—she was in certain respects a girl victor over Hitler. What stopped me in my tracks when I previously tried to write her story were my feelings as a mother—I thought of my grandmother being unable to protect her children. What happened to members of my family and others who were so brutally murdered is shattering—not because I am Jewish or a scholar, but because I imagine individuals’ final hours.

Can you describe some of the feelings and emotions you had to process while you completed interviews with survivors other than your mother?

When I interviewed other survivors, I focused on capturing their stories in whatever ways they chose to tell them. I tread cautiously and respectfully, but the need for me (as researcher) to know was paramount. Except for especially sensitive souls (like my father) most of the survivors I “interviewed” were very willing to describe the horrors they witnessed and endured. I felt honored to have their trust.

Brigadier Hugh Llewelyn Glyn Hughes is a hero of World War II and was the first man to testify at an international war crimes trial. Given the fact that there are no books (until now) written about him, do you believe history has forgotten him? Why?

There must be thousands of unsung World War II heroes. Oskar Schindler was one of them until Thomas Keneally told his story in his fact-based novel, which Steven Spielberg read and decided to take to the screen. So it’s not that history has forgotten Glyn Hughes, it is that someone had to realize the significance of his deeds, determine that he was biography-worthy, and lift him into bold relief. As far as his role as first witness at the first international war crimes trial, I believe the high profile Nuremberg Trials eclipsed the Belsen Trial, which ended just before the first of the series of military tribunals—the Trial of Major War Criminals—began.

Can you speak to who Glyn Hughes was as a man, before the war?

Glyn Hughes had risen from difficult childhood circumstances to become a World War I hero, a successful obstetrician-gynecologist, and a well-known sportsman. He had a very busy life—when I gained a sense of his many volunteer, professional, and social activities, I wondered how he found time to sleep! He was a warm and caring father, son, colleague, and friend. He was a good provider, but he and his wife had a strained marriage.

How did Glyn Hughes’s experience at Bergen-Belsen continue to impact him after his participation in the liberation?

Glyn Hughes had a soul-turning experience in the months after the liberation. At first, he felt intense shock and sorrow—how was he going to deal with the unprecedented, horrific situation? Once matters got somewhat under control, he witnessed extraordinary and moving phenomena: survivors who the British Second Army would have left for dead began to recover, and soon became part of a vibrant post-war community. He remained interested in and in touch with survivors for the rest of his life, and considered his role in saving a remnant of the Jewish people to be his crowning achievement.

Bergen-Belsen was not liberated in one day; and prisoners continued to be murdered even after April 15, 1945. Why do you think we so often talk about liberation as if it was a singular moment in time?

This is a misconception. All rescue missions take time, and even those who are knowledgeable may not understand just how chaotic and desperate things were at Bergen-Belsen and how ill-prepared the Allied armies were for what they happened upon. I hope that my book will be a corrective to false assumptions, as it details the ongoing struggles of those who had managed to survive to that point, as well as the great many challenges the liberators faced in their rescue efforts.

The conditions and “purposes” of each concentration camp differed from one location to another. What separates Bergen-Belsen from a camp like Auschwitz?

The conditions and “purposes” of many of the concentration camps changed over time. Auschwitz had evolved into a highly industrialized death factory; Bergen-Belsen had morphed from a POW camp and camp for “exchange prisoners” into a dumping ground for inmates evacuated from camps in the East. Survivors who endured Auschwitz and then wound up in Bergen-Belsen described the former as an orderly type of hell, where people were killed and incinerated en masse, and the latter as a place where the dying and dead were visible everywhere. The Nazis executed plans in Auschwitz; they had no plans and absolutely no provisions for the overwhelming numbers of war-ravaged prisoners arriving in Bergen-Belsen.

Why do you think we tend to remember some camps over others (i.e. International Holocaust Remembrance Day commemorates the liberation of Auschwitz, rather than any other camp)?

As the largest number of victims of the Holocaust—more than 1.1 million people—were murdered in Auschwitz it has become a symbol of the evil of the Nazi regime. So it was perhaps natural (though somewhat strange to those who know the history) that the day that the Russians entered Auschwitz and found 7,000-7,500 sick inmates has been chosen as Holocaust Remembrance Day. Where and when were other survivors liberated? Allied soldiers found inmates on the road, in various camps, in deserted trains; the largest number of barely alive inmates were liberated two and a half months after the liberation of Auschwitz, in Bergen-Belsen.

Your mother, upon immigrating to the United States, chose to change her name: from Rachel Genuth, to Ruth Mermelstein. What is the reason behind this decision?

My mother has had many names. Her birth name was Rachel; her Romanian name was Regina. After the war, when she was taken to Sweden, she was officially registered as Rosalia and called Rosie. When she married my father and came to the United States, he said she should be called Ruth (he knew an American by that name). She also took his last name, Mermelstein. (My father, too, had a different name in each country in which he lived.)

Glyn Hughes was responsible for saving the lives of thousands of Bergen-Belsen prisoners, including your mother. Though Rachel and Glyn never officially met, has your mom been able to speak with his descendants? If so, how did that conversation go?

My mom never spoke with Glyn Hughes’s descendants. Glyn Hughes’s children never met any of the survivors saved by Hughes and the British Second Army. He kept that part of his life separate, telling them very little about Bergen-Belsen. But they knew when he or he and his wife Thelma would be traveling to visit “the Jews,” and that some among them were his personal friends.

What makes All the Horrors of War unique amongst Holocaust literature?

It takes a very deep dive into the question of how a young girl survived, going so far as to examine the life of the man who had foremost responsibility for relief and rescue efforts at Bergen-Belsen. In so doing, it tells a larger story, about those in the positions of two diverse protagonists, who owing to wartime developments arrived at the same godforsaken place; about human suffering, courage, and compassion. As far as I know, there is no other book like it in the canon of Holocaust literature.

Finally, what do you hope readers take away from this book?

I hope readers will realize that we always have a choice of how to act in our encounters with others—we can choose to see them not as strangers, but as sacred human persons. Glyn Hughes, a hardened military leader who had seen all the horrors of war, felt empathy for Bergen-Belsen inmates who had been utterly degraded and dehumanized by the Nazis; he exemplified the human capacity for compassion. More than many British officials, and British doctors who took charge of the Glyn Hughes hospital in its later years, he appreciated the dignity of each individual, regardless of his or her race or religion.

Order All the Horrors of War: A Jewish Girl, a British Doctor, and the Liberation of Bergen-Belsen – published on April 14, 2020 – at the following link: https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/all-horrors-war

Bernice Lerner, the daughter of Rachel Genuth, is a senior scholar at Boston University's Center for Character and Social Responsibility. She is the author of All the Horrors of War: A Jewish Girl, a British Doctor, and the Liberation of Bergen-Belsen, The Triumph of Wounded Souls: Seven Holocaust Survivors' Lives, and a coeditor of Happiness and Virtue beyond East and West: Toward a New Global Responsibility.