Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

All Our Names

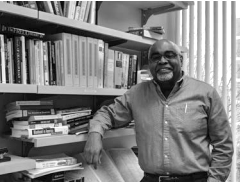

Nathan Grant has served as editor of African American Review since 2008. An Associate Professor at St. Louis University, he has agreed to republish his introduction to the issue celebrating the journal's landmark 50th anniversary here on our blog. Issue 50.4 has collected works from throughout the journal's history from many notable names. The issue is accessible on Project MUSE.

These are just a few of the names whose works have graced the pages of African American Review over the last fifty years. It’s an impressive and weighty list in its entirety—names of poets, fiction writers, and scholars who have given expression both wide and deep to the experiences of African America and the larger African diaspora, and who have also shared their visions with AAR. Our fiftieth anniversary is an opportunity to thank them for doing so, because our partnerships with them have made us to be but one of many means through which pan-African culture and its continuing messages of equity, justice, and empowerment—again, just to name a few of these—remain at the center of American life, both within and beyond the academy. I’ll also take this opportunity to thank John Bayliss, Joe Weixlmann, and Joycelyn Moody for not only engineering and continuing this journey, but also for entrusting it to me.

I’d asked myself, when I’d learned in 2008 that I was being recruited by Saint Louis University to become the next editor of African American Review, just what this position must be like. I knew that the job had been announced the previous year and thought at the time that it’d be nice for someone, thinking as I did that I was reasonably comfortable at the University at Buffalo. (Well, except during winter.) “So,” I’d said to friends, not knowing quite what to expect, “I’ll finally get to see the Gateway Arch in the flesh!” I’ve seen it, but I’ve now been here ten years, and have yet to go into and up the thing, which you can do. As a native New Yorker, I’d worked as a graduate student in one of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, never having been there except for work, and it was a revelation to me then that there could be such a thing as both an “express” elevator and a “local” one in the same building, believing all my life until then that that was a feature reserved to the subway! (When Colson Whitehead debuted The Intuitionist in 1999, I berated myself for not having committed the idea to paper before him.) I also visited the Empire State Building for only the first time on a trip back to New York last year because, um, after all that time, you have to. So I guess my casual neglect of the Arch must signify that St. Louis is now what I call home.

But I’ve found (as I’d mostly expected) that as you move, and perhaps especially as a person of color, your experiences tend to precede you as much as they follow you; they will meet you at your destination, and they will be pleased not to ask for the claim check. They will even wait at the door of the new place, always arriving before the furniture does—indeed, they are the new furniture, and they will require new arrangements in a different space. Self-reinvention, what we often feel to be the peculiarly American adventure of not only reorienting one’s body and consciousness to newness, but also changing these entirely, is always possible, but it depends upon unique negotiations between the self and its dwelling. “Travel makes the person,” chirped Jean Toomer’s Costyve Duditch, practically before leaping toward each next venue, and I’ve wondered time and again if Costyve knew just how right he was, and also whether he’d ever felt what was later so keenly expressed in the (old?) Kenny Gamble-Leon Huff R&B tune sung by Teddy Pendergrass, “You Can’t Hide From Yourself.” Because, you see, everywhere you go, there you are.

Michael Brown. I hear Michael’s name often now in St. Louis, especially as I live and work not at all far from Ferguson, Missouri; it’s a name that’s spread through this city and county, as widely as is the wind in the trees. And the others also heard from are not so far, but rather quite near, as in this age they exhort us toward the work we must do. Stuart Hall, Nina Simone, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Toni Morrison, Adrian Piper, Glenn Ligon, Bill T. Jones, Amiri Baraka, Suzan-Lori Parks, and countless others have all believed that the fractured promises of modernity as bequeathed by the Enlightenment must be, vigorously and consistently, assaulted from below. We do not deny the evidence of significant change, but we dare not also say it’s not getting worse. Plus les choses changent: just as then, this is how we live our lives now.

I am always compelled to think, however, that AAR has been an important part of the continuing effort toward the kinds of change that can come from the expansion of minds, and that it has existed precisely in this way for the last half-century. Of necessity, it’s large and loud, but its size comes from its multiplicity of voices, and it must therefore be heard. And listened to. From Black Consciousness to #BlackLivesMatter, AAR has been incisive in its outlook because its contributors have boldly executed their ideas in it. And so I’m indeed fortunate to be in the editor’s chair, watching it all take shape; listening to the conversation form, bend, and sometimes break, and then re-form, as it will; reading and mapping all of the ideas and the names of those associated with them, all our names—and hoping with them that if the best answers to our most crucial questions cannot be fashioned now, they will, hand upon hand and voice with voice, soon shape the ends of our most urgent conversations. In this spirit we together turn the next page.