Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

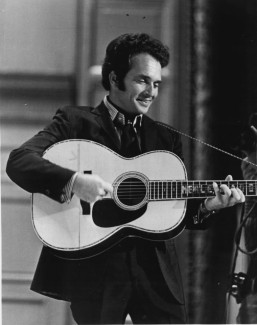

Analyzing Merle Haggard

The Fall 2018 issue of American Imago featured a pair of articles with a unique focus for the renowned psychoanalysis journal – country musician Merle Haggard.

Journal editor Murray Schwartz was part of a team which awarded the prize, and Howard M. Katz agreed to respond to Wheeler’s paper due to his interest in music and human development. Katz, who is a Training and Supervising Psychoanalyst at the Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute and Lecturer in Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, published “Music, Bonding, and Personal Growth: Merle Haggard's Musical Journey toward Wholeness. Discussion of "A Place to Fall Apart, A Reading of Merle Haggard's Music" by Richard P. Wheeler.”

With coordination from Schwartz, Wheeler and Katz agreed to participate in a Q&A about their articles on Haggard’s music and its relevance to psychoanalysis.

Dr. Wheeler, what spurred the development of your essay?

When I retired from the University of Illinois, after many years of administrative work and writing very little apart from reports and memos and emails, I wanted to give writing a try again. But I didn’t want to jump back into the Shakespeare criticism wars, and I did want to find a way to think and write at least a little differently from the style and manner of my past scholarship. And Merle Haggard’s music provided a way of moving away a bit from Shakespeare and British literature and moving closer to my own life as it was shaped by music I listened to – when I was growing up, and again later when I came to understand how important that music had been to me, and how brilliantly it was being extended by country western singers of Haggard’s generation.

Dr. Wheeler’s fine paper was the recipient of the Silberger Paper Prize at our Boston Psychoanalytic Society and Institute. I had a role, along with Murray Schwartz and others, in creating that program, that recognizes the value of applying psychoanalytic understanding to the efforts in the arts, sciences and humanities to deepen our understanding and appreciation of the human condition. The committee that awarded the prize knew of my deep interest in that common ground and some psychoanalytic explorations of my own of the deep emotional chords struck in the work of writers and artists. Having pursued that interest in the development of an undergraduate course on the relation of dreaming to artistic acts of imagination and in discussions of films, including some about music or musicians, I jumped at the chance to respond to Dr. Wheeler’s paper. Reading it and immersing myself in Haggard’s music touched me and provided another point of access to the role of music in emotional life. My response emerged from the feeling at the intersection of a life story and an engagement with the music.

What made American Imago the right venue for these essays?

RW: American Imago traces its existence to Freud’s and Hanns Sach’s creation of a journal to bring psychoanalytic insight and method to a wide range of cultural topics. Placing the article in that journal carries special meaning for me because of the place Freud occupies in my intellectual development and because of my conviction that psychoanalytic thought can bring into view crucial dimensions of artistic and cultural productions.

HMK: American Imago has a rich history as the preeminent journal devoted to the psychoanalytic perspective on literature and the arts. Its readership, itself, serves a bridging function, bringing together scholars in a wide range of fields with the practicing psychoanalysts and students of evolving psychoanalytic theory. The journal is a meeting place for perspectives arising from diverse corners of our universe of ideas about the life of the mind. As such, it seems like the place for a professor of literature to enter into dialog with a practicing psychoanalyst as they step out of the comfort zone of either into the world of country music.

RW: If I were writing about what I think of as “pop culture,” I would be inclined to write about it as symptomatic – as cultural production that reflects back elements of the social world that produced it more than it significantly reflects on that world and illuminates it with enriched, psychologically nuanced, understanding. In the songs he wrote and sang, Haggard brought the depth of a brilliant, courageous, loving, troubled psyche into full engagement with the world he experienced, and brought it back into his music with that depth intact. When an entertainer can do that, why should he or she not be taken seriously by academic writers?

HMK: Why are many millions of people entertained and, beyond that, moved by some products of pop culture? It is no accident. Some narratives and images and, in the world of music and dance, some calls for moving one’s body to the music touch deeply felt reservoirs of feeling and meaning, highly individual and yet in ways widely shared. These cultural products mean a great deal to people and, yet, this is a relatively neglected area of inquiry among more serious students of emotional life. Dr. Wheeler is an esteemed Shakespeare scholar and he may be able to address, better than I, the question of whether we could see Shakespeare, in part at least, as entertainer or purveyor of the culture popular in his time. For my part, I see value in looking at the chords struck not only by esteemed artists whose work has stood the test of time but also by those of our own time.

Dr. Wheeler, how important is it for someone like you to publish research in a new area after a distinguished career?

It was important for me. I am hoping I can complete a related venture on the importance of capturing deep sadness in country greats like Jimmy Rodgers, Hank Williams, Bob Wills, and George Jones, as well as Haggard. And I am hoping that exercise (which is proving to be difficult) will free me to return for a while to things Shakespearean. Regardless, the experience of writing about a vocalist/songwriter whom I great admire, but who did his work in a realm of creativity far removed from the literature I was trained to think and write about, was deeply satisfying.

Dr. Katz, how important is a response paper like yours in academic publishing?

Published papers that stand alone may stimulate reader’s thinking in such a way that the reader is in dialog, in a sense, with the author. I think that a published response may add to that stimulus and open more possibilities for responsiveness in readers. In some instances, a respondent enters an argument with the author, agreeing here, disagreeing there about the assertions of the paper, hopefully widening the scope of thinking in that way. I chose another tack, seeking to complement Dr. Wheeler’s thoughtful consideration of a kind of working through of grief and trauma in Merle Haggard’s songs, that focused largely on lyrics, with an explication of how the musical form itself may be a vehicle for expressing emotion and connecting with others - those of one’s present and of one’s past. I add a bit of the biological and developmental perspectives to the more literary and biographical elements so well described by Dr. Wheeler. Hopefully readers are invited to reflect on the healing musical journey of this one talented man, Merle Haggard, as exemplifying multifaceted ways in which music contributes to the affective coloring of life and to the feeling of vitality.