Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Are our National Parks for animals or people?

The National Park Service (NPS) celebrates its centennial anniversary in the month of August! NPS has served as a valuable resource for many of our authors, both professionally and recreationally. To commemorate the occasion, our authors have taken to the blog to pay homage to “America’s best idea”! Check back with us throughout the month of August for more #JHUPressOnNPS! (Series photo credit: Wikimedia)

Our National Parks are more popular than ever. This is a good thing - more people visiting our country's natural areas means more people getting exercise, connecting with nature, and contributing to the outdoor recreation being the 3rd most important part of our economy. But you can also have too much of a good thing, and park rangers are challenged with making sure we don't love our parks to death. Too many people and cars not only reduce the natural beauty of an area, they can also scare away the animals.

Parks are not just for our enjoyment, but also need to protect the other species that rely on these big natural areas as critical habitat. Park managers have to balance this dual mandate of preserving nature while also allowing use of the area by people. Hiking is probably the most widespread recreational activity. Every park has its trail network, helping visitors see the remote parts of each park not accessible from the roads. However, if animals are disturbed by hikers, these trails could be destroying the last peaceful refuges for wildlife.

Previous research has shown that wildlife will run and hide from people using park trails, especially when they are accompanied by a dog. However, the long-term effects of this avoidance were unknown, leading us to start a new project testing for the effects of hiking trails on wildlife. We set triplets of motion-sensitive camera traps with one aimed right at the trail, one set near the trail (~50 meters) and one set far from the trail (~200 meters). The on-trail camera counted people as well as wildlife, and allowed us to see if animals avoided the busiest trails, or if they generally avoided all trails, hiding out only in the most remote parts of a park. We worked in 32 parks across six mid-Atlantic states. To get our cameras into all these areas we worked with the hikers themselves, enlisting over 300 volunteer citizen scientists to set the cameras, go through the pictures, and share the data with us.

After running cameras in nearly 2000 locations our results showed that wildlife and people, for the most part, can share the trails. One of my favorite examples was a camera run on a trail for three weeks in Shenandoah National Park that detected people 107 times but also photographed a ton of animal activity including black bears (14 times), bobcats (5), white-tailed deer (5), coyotes (3), and raccoons (2).

Our statistical models showed that most species were found as often off trail as on-trail. Predators like bobcat and coyote were actually photographed more on the trails, which they seemed to use as movement highways, although mostly at night, after all the hikers have returned to their homes or tents. Bobcats avoided the busiest of trails, while red foxes were actually photographed more along trails with lots of human use.

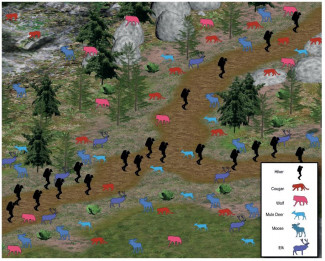

A similar study in the Rocky Mountains found that prey species actually concentrated around the busier hiking trails, which were avoided by predators. Elk and deer have quickly habituated to the high levels of foot-traffic, effectively using the hikers as a 'human shield' against the shyer cougars and wolves.

These studies show that, when it comes to wildlife, park managers are doing a pretty good job at balancing the needs of people and biodiversity. Hopefully they also encourage more people to go for a hike, just keep an eye out for the animals, they are using the same trail network as you!

Roland Kays, Ph.D. is a scientist at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and NC State University. He is the author of Candid Creatures: How Camera Traps Reveal the Mysteries of Nature.