Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

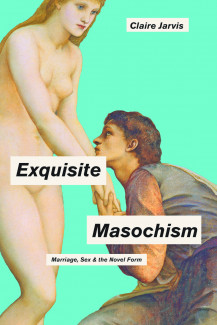

Behind the book: A Q&A with Claire Jarvis

Q: Why did you decide to write this book?

I wrote Exquisite Masochism because I noticed striking similarities in the ways sexually aggressive women characters were used in nineteenth century novels and I wanted to know why.

Often, we think of the nineteenth century as a period when sexuality was repressed and, if not repressed, channeled into the powerfully stabilizing structure of the intimate, domesticated family. At least since Michel Foucault and Steven Marcus, critics have drawn attention to the ways the idea of repression ignores the way perverse sexuality, particularly what we’d now call gay and lesbian sexuality, helps to structure and define the kind of bourgeois domesticity we associate with the nineteenth century – that whole “lie back and think of England” canard.

But my hunch was that there might be a way to see sexual power bubble up even within heterosexual romance plots. What I noticed, as I read, was that many, many authors use sexually potent women characters to “test” the limits of representation in otherwise respectable novels. Once I started noticing these characters as a group, I began to see how much the authors’ uses of them varied.

Q: What were some of the most surprising things you learned while writing/researching the book?

By far the most surprising discovery appears in the last chapter, “Dead Gems.” While I was researching this chapter, I was able to visit the Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, to look over the collection of Lawrence’s typescripts housed there. I had been working on The Rainbow and Women in Love for some time by then, and I felt there was a strong connection between the character of Hermione Roddice and the kinds of sexually dominant characters I’d noticed in earlier novels. When I say I “felt” the connection, I mean it in precisely that inchoate way – I read Hermione as having a similar character shape, but I had no proof that she could be read that way. After all, Lawrence was writing her in the 1910s, and he was writing her in a much more explicit frame than any of the novels I’d treated thus far.

Well, as I worked through the typescripts, I found some evidence that Lawrence himself had been working through Victorian aesthetic theory while writing Hermione and then, close to the end of my research period, I discovered what I think of as a smoking gun! It’s detailed in the book, but it leaves no doubt in my mind that when Lawrence was writing Hermione he was working through his ambivalence and then distaste for a Paterian aesthetic framework. Being receptive to these kinds of hunches is precisely what I mean when I describe “perverse formalism” in the Conclusion of the book. I don’t think I could have imagined a better piece of evidence for the book’s central claim, that these sexually powerful female characters were a profound structural innovation for the realist novel, and it was right there, in the archive!

Q: What is new about your research that sets it apart from other books in the field?

Books about marriage, especially marriage in the nineteenth century, tend to focus on two aspects of the institution: 1) its power to stabilize and license sexuality and 2) its capacity to reinforce patriarchal structures. Instead, my book looks at the way instability and vulnerability run through many of the marriage plots that most define the nineteenth century novel. Further, by looking at the ways women characters were imagined as sexual agents, I want to put some pressure on accounts of the marriage plot that emphasize the damaging and controlling ways nineteenth-century marriage limited women’s choices. I think the best way to do this is by focusing on the formal elements of the novels in question, in part because the history of the period is, make no mistake, patriarchal. But also, it’s my hope that by emphasizing the deeply erotic connections at the cores of many canonical plots, Exquisite Masochism offers a new perspective on the ways nineteenth-century novelists represented and thought about sex’s equalizing potential, particularly in and around marriage.

Q: Does your book debunk any longstanding myths?

The biggest myth my book debunks is that the nineteenth century novel wasn’t explicit about sex. It was—we just lost our capacity to read these scenes as sex scenes. And we can’t read these scenes as sex because we live in a world totally conditioned by modernism’s explicit explosion of older habits of sexual representation. In terms of sexual representation, we totally buy what modernism is selling. By including a chapter on the very sexually expressive modernist D. H Lawrence, and by suggesting a clear conceptual line connects Lawrence’s representations of women to the earlier novelists’ representations, I think readers will see the earlier scenes in a new, explicit light.

Q: What is the single most important fact revealed in Exquisite Masochism and why is it significant?

This is not a book about facts. It’s a book about interpretation. I have always thought that this book offers a new rationale for interpretive criticism, which is its most significant contribution to literary studies. In developing this book, I read a lot of older literary criticism, criticism that was unashamed of its status as interpretation. We live in a critical world conditioned by facts and proveability, but by focusing on these aspects we miss a lot of other ways of marshaling evidence to support our claims. There are plenty of places where my argument is proven in this book – the archival evidence I cited earlier, for example, or the historical conditions of women in the period I discuss. But I want to stress that the readings themselves are also evidence – evidence that doesn’t need the historical or factual ballast to be persuasive. In other words, the kinds of things I count as evidence for my argument, from the inchoate hunch that led me to begin researching this book to the hard evidence I found in the archive, varies quite dramatically over the course of the book, and I want to encourage critics and readers to use everything at their disposal to make their arguments – this is a call to a more capacious, less cautious form of literary criticism.

Q: How do you envision the lasting impact of your book?

As I said above, I think literary criticism has become too cautious in its claims. When I read someone like Raymond Williams or Dorothy van Ghent, I’m shocked by the audacity of their claims, and the ways they feel a license with their texts that we – working after deconstruction and post-structuralism – may not feel, despite the ostensible license those theoretical approaches offer. I don’t think this is a call to irresponsibility, I don’t think we should ignore historical truth or fact when we work through literary texts, but I do think readers should feel the weight of their own interpretations more powerfully. Spending a long time pouring over a small passage of text – what we might think of as close reading – has become harder and harder to justify in our current critical climate, and some things are counted as close reading that are really just reading. What I’m demonstrating in Exquisite Masochism is a kind of reading that actually produces the sensation of a text buckling under the weight of one’s attention, a reading that almost – but not quite – destroys the words on the page.

Q: What do you hope people will take away from reading your book?

First, I hope people will look for and find pockets of deep eroticism in other texts. The novels I treat here are by no means the only novels in which these characters and these structures appear, and I hope this book encourages people to read nineteenth-century texts differently. And my other, more general, hope is that people will come away from this book with a sense of the profound pleasure reading carefully can yield.

Claire Jarvis is an assistant professor of English at Stanford University and author of the new book, Exquisite Masochism: Marriage, Sex, and the Novel Form.