Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

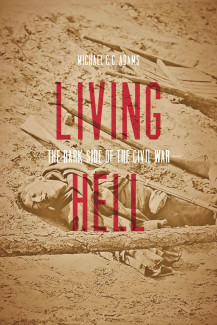

Civil War Unmasked in 'Living Hell'

This post is part of our July “Unexpected America” blog series, focused on intriguing or surprising American history research from 1776 to today. (Photo Credit Nicholas Raymond)

Often I am asked what most surprised me during the researching of Living Hell. My answer is consistent: what I did not expect was the startling candor with which our forebears related their experiences. We often think of the Victorians as close-mouthed, even repressed about many matters, particularly their most intimate physical and emotional experiences. But this really was not the case.

A soldier might write his brother to say that the boys were desperate enough for sex to be out hunting brothels all across town. Or, after having had their fun with a brain- addled young prostitute, they tossed her off a bridge. A hospital inmate might tell a friend almost proudly that he was enduring the mercury treatment for venereal disease. A Union quartermaster in the occupied South could confide to his diary that he had bought a starving mother for a bag of flour or train tickets out of hell for her and her children. And a provost commanding a village might boast to his journal that he had spent a night with Venus for the price of a cup of sugar.

Civilians, too, talked of their war experiences in frank terms. Women described the terrible experience of losing loved ones on far fields. Their diaries relate the sufferings of sisters and mothers who miscarried through fear of the invading armies. Or they documented the rape of slaves by raiders on both sides. Some, like aristocratic South Carolinian Mary Boykin Chesnut, admitted to their diaries that they took opium and laudanum to soothe their nerves enough to cope with the stress of war. Mary worried at times that she had become an addict.

The harsh reality of combat was by no means always glossed over with romantic phrases. A soldier might describe the landing in his mess tin of a comrade’s brains after a shell smashed his skull open. Or a memoirist surprised his readers by admitting that he screamed when a staff officer, riding across his unit’s front, suddenly had only half a face; shrapnel had carried away his lower jaw. Veterans pictured shreds of flesh blown into trees and faces so smashed by minié balls they resembled pink sponges. We read of corpses without limbs or heads, bodies of dead and near dead charred by fire and eaten upon by hogs. At times a man will admit that he put a viciously mutilated comrade out of misery with a bullet.

To a degree, we have these remarkably vivid descriptions because this war was the last major American conflict in which there was no official censorship, a curse to the generals but a boon for historians. And in an age of general literacy in which books were a major form of entertainment, memoirs by veterans proliferated. Yet, as a public narrative of America’s greatest war developed, emphasizing chess board moves by generals, acts of gallantry, heroism, and willing sacrifice, much of what had been starkly written came to be passed over, overshadowed by the positive narrative of epic struggle between blue and gray. And yet, voices uttering much more complex, often darker truths have lain quiet in our libraries, waiting to be rediscovered by those who wish to hear them.

Michael C. C. Adams, Regents Professor of History Emeritus at Northern Kentucky University, is the author of The Best War Ever: America and World War II and Our Masters the Rebels: A Speculation on Union Military Failure in the East, 1861–1865, winner of the Museum of the Confederacy’s Jefferson Davis Prize for the best Civil War book. His most recent book, Living Hell: The Dark Side of the Civil War, will become available in paperback in August, 2016.