Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

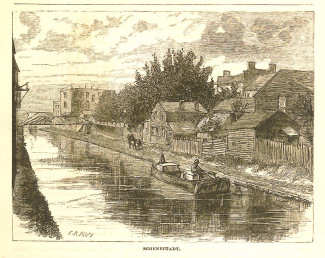

The Erie Canal’s bicentennial: a reminder of what happens when wealth, politics, and science converge

Two centuries ago, when the richest man in America ran for higher public office, he prioritized the public good above personal gain, and he cultivated American science and technology as key potential contributors to general prosperity. Stephen Van Rensselaer’s behavior certainly contrasts in interesting ways with the political realities of the early 21st century in the United States. Readers of DeWitt Clinton and Amos Eaton: Geology and Power in Early New York learn about how the Erie Canal’s construction initially depended upon, and then, in turn, boosted, the growth and development of American geological theory and practice.

DeWitt Clinton was the newly elected New York governor on July 4, 1817, when he thrust a shovel into the ground at Rome, New York to initiate the ambitious 350+ mile-long canal construction project. A Jeffersonian Democrat, Clinton shared very few things in common with the Federalist Rensselaer, but there were three key points on which these two men agreed.

- Both shared an abiding personal fascination for the natural sciences.

- Both had befriended and patronized the scientific investigations of local naturalists (botanists, chemists, zoologists, and geologists).

- Despite their partisan differences, they frequently worked together (on formal commissions, in learned societies, and through informal networks and correspondence) to mobilize private and public financial resources, in order to employ native scientific talent to address social needs. Efforts to improve the effectiveness of agricultural practices, and the extraordinary challenge of building a navigable canal across the entire state, were just two of the projects that the political rivals Clinton and Rensselaer would jointly take on.

The book also features the peculiar and remarkable career of Amos Eaton, one of those local upstate New York naturalists. Eaton certainly led a checkered life, but a chance meeting with Clinton lifted him out of terrible misfortune. With Clinton’s political power and Rensselaer’s financial patronage, Eaton rebounded incredibly from the harsh experience of being convicted on a trumped up charge of forgery (receiving a life sentence at hard labor in New York’s Newgate Prison) to become the founding professor of the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and the creator of New York state’s first comprehensive geological map.

My exploration of the intersecting lives and careers of the Erie Canal and New York’s early 19th-century scientific community extends well beyond these three featured individuals. One of the most fascinating discoveries I made as I researched and wrote this book involved the pervasiveness of geological questions across all aspects of society. The more I tried to pin down scientific conversations among a few key participants, the more I saw how they overlapped with other matters of debate and forms of cultural creativity in early New York. The final third of the book traces patterns of interaction and mutual influence among New York’s geological features, the scientific debates that those phenomena spawned, the inspirations that fueled works by prominent New York literary figures and Hudson River school landscape painters, and the impact that changing notions of the scope of Earth’s history were having on contemporary religious beliefs.

David I. Spanagel is an associate professor of history at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. His book, DeWitt Clinton and Amos Eaton: Geology and Power in Early New York, is now available in paperback.