Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Now Browsing:

Fall migration Is underway

Guest post by Leslie Day

On the next to last day of September 2015, I was walking in Fort Tryon Park in Washington Heights from the Heather Garden. Just before I got to Sir William’s Dog Run, my eye caught a movement high up in the northern red oak tree. Warblers! Knowing it’s migration time for insect- and nectar-eating birds—i.e. warblers, flickers, kinglets, hummingbirds—I never leave home without my trusty, light-weight pocket binoculars. Let me tell you, it is challenging keeping your binoculared eyes on moving warblers. The balletic pattern of one of the warblers foraging in the oak tree made me think REDSTART! These tiny birds—black and red males, gray and yellow females—flash their tails and dive up and down, in and out, gleaning insects from the leaves. I had spotted a lovely female redstart fanning her bright yellow tail and flitting, butterfly-like, from leaf to leaf.

There was another warbler with a different type of motion. Catching up to him with my eyes, I saw it was a male northern parula warbler: a gorgeous little fellow with olive shoulders and a back, gray head, a bright yellow belly turning orange up by his neck, and a black necklace. What a find!

The next afternoon I met Kellye Rosenheim leading a tour for New York City Audubon. We met at the salt marsh of Inwood Hill Park. The park is located at the northernmost tip of Manhattan Island right next to the shipping canal that connects the Harlem River with the Hudson River at Spuyten Duyvil. So much to see there. The week before, birding with my friend Elizabeth White-Pultz, we saw a marsh wren and a pair of common yellowthroat warblers hanging out in the marsh grass, flowering goldenrod, and asters. Columbia University has their boathouse there with a new kayak dock that is used by the rowing crews and the public. Columbia has housed their boats up there since the late 1920s. Across the Harlem River you can see a giant blue and white C. In 1952, Robert Prendergrast, a Columbia medical student and coxswain of the rowing crew, painted the letter on the massive Fordham gneiss outcropping. From the marsh we walked up into the verdant hills of the park. Entering the deeply forested paths, we found black-throated blue warblers, male and female redstarts, northern flickers, and a white-breasted nuthatch.

Fall migration happens more slowly than spring migration, when literally hundreds of millions of birds take the aerial route known as the Atlantic flyway from their winter feeding grounds in South and Central America to their northern breeding grounds in the middle Atlantic states, New England, and Canada. Flying over New York City, they drop down in huge numbers into our parks to feed and rest. Sometimes they stay, nesting and raising their young until it is time to make their journey south in order to find food throughout the winter. And so it is that birds leave our area, not because it is too cold in winter—after all they are covered in a layer of down, just like our down coats that keep us warm and cozy in January, February, and March. But birds cannot find the food they need in the winter: insects and other invertebrates, fish, amphibians, small mammals. In addition to watching migrating warblers and other song birds, during fall migration you can join groups looking at migrating hawks, eagles, and owls; egrets, herons and shorebirds. And from the far north come our wintering birds, which are able to survive the cold months in New York City. Small flocks of tufted titmice, white-breasted nuthatches, and black-capped chickadees descend on our wooded parks. And in autumn and winter we make way for ducks, geese, and swans! Wood ducks, northern shovelers, hooded mergansers, ruddy ducks, snow geese, brandt geese, and mute swans flock to our wetlands to find food when their summer territories freeze over. They are not alone. More and more, we are seeing bald eagles along our coast in winter.

And of course we have our year-round birds who are able to find seed, nuts, and dried fruit even in winter: blue jays, house sparrows, crows, starlings, pigeons, cardinals, downy, hairy, and red-bellied woodpeckers, mallard ducks and Canada geese. And let us not forget our birds of prey that are here all year: red-tailed hawks, cooper hawks, sharp shinned hawks, peregrine falcons, American kestrels, great horned owls, saw-whet owls, and screech owls. New York City, as it turns out, is a birding haven throughout the seasons. So take a walk with or without binoculars and you will start to see our lovely and interesting feathered neighbors.

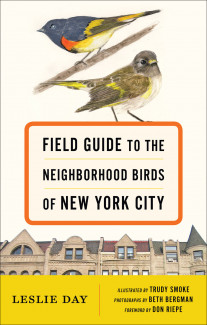

Leslie Day is a New York City naturalist and the author of Field Guide to the Neighborhood Birds of New York City, Field Guide to the Natural World of New York City, and Field Guide to the Street Trees of New York City, published by Johns Hopkins. Dr. Day taught environmental science and biology for more than twenty years. Today, she leads nature tours in New York City Parks for the New York Historical Society, the High Line Park, Fort Tryon Park Trust, Riverside Park Conservancy, and New York City Audubon. Trudy Smoke is a professor of linguistics and rhetoric at Hunter College, City University of New York and a nature illustrator. She is the illustrator of Field Guide to the Street Trees of New York City. Beth Bergman is a photographer for the Metropolitan Opera who moonlights as a nature photographer. Her photographs have appeared in numerous publications, including the New York Times, Newsweek, New York Magazine, Opera News, and Paris Match.

Login to View & Leave Comments

Login to View & Leave Comments