Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Five Things That Will Surprise You about Civil War Medicine

I once heard historian Drew Gilpin Faust tell an audience at the National Humanities Center that at least one book about the Civil War had appeared for every day since Lee surrendered at Appomattox. That’s a major challenge for the historian who seeks to say something new about the topic. So, in the spirit of the common blog theme . . .

Here’s Five Things That Will Surprise You about Civil War Medicine!

1. Surgery was humane and, often, successful.

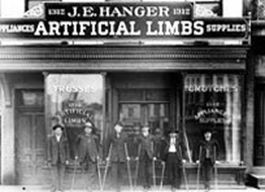

Surgeons used both ether and chloroform during the war, performing all of those amputations that are emblematic of their craft. The Mutter Museum recently surveyed visitors to a Civil War medicine exhibit and found that 89% thought these operations were done without anesthesia. Perhaps the scene in Gone with the Wind in which Scarlet hears a man screaming off stage has created this impression, and indeed the peculiar circumstances of the Atlanta siege may have led to such medical horrors, but most men were asleep as they lost limbs to the surgeon’s saw. And around 75% of major arm and leg amputations healed, leading to a brisk business in prosthetics after the war.

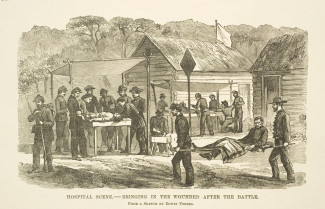

2. Civil War hospitals were actually houses of healing.

Around 95% of most sick and injured men who arrived at the general hospitals of the war survived. General hospitals were the big institutions far from the lines of battle, where thousands of men were housed and treated. However, as Cold Mountain illustrated, toward the end of the war Southern hospitals were very short on food, and patients had to escape to avoid starvation.

3. Women had a major role to play in Civil War hospitals.

Before and after the war, most medical care happened in the home; in an era when professional nursing was in its infancy, women had caregiving skills learned in the home and transferred to soldiers in the hospital. They knew, for example, the simple importance of food, water, cleanliness, and distraction. Women were the backbone of the United States Sanitary Commission, a Red-Cross like entity that supplied northern hospitals with clothing, bedding, and nutritious food supplements. Lemons, oranges, and even the lowly potato made a huge difference in healing for wounded and ill men.

4. The war changed the course of American medicine and public health.

One major lesson was the ability of disinfectants to limit disease, even before a clear understanding of the relationship between microbes and infection was known. The widespread dissemination of their power paved the way for ideas about antiseptic surgery and public health measures dependent upon disinfection. The war, in general, was a vast educational enterprise for spreading modern medical knowledge to every corner of the American medical world.

5. Titles are more important than you might think.

The phrase "Marrow of Tragedy," suggested by my Johns Hopkins editor Jacqueline Wehmueller, comes from a quotation in the introduction by Walt Whitman. Amazon picked up on that phrase and recommended Marrobone dog biscuits to those who liked the book!

Margaret Humphreys is the Josiah Charles Trent Professor in the History of Medicine, a professor of history, and a professor of medicine at Duke University. She is the author of Intensely Human: The Health of the Black Soldier in the American Civil War, Malaria: Poverty, Race, and Public Health in the United States, Yellow Fever and the South, and, most recently, Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the Civil War.