Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Gamer Nation

One of my favorite movies from the 1970s is Richard Fleischer’s science fiction thriller Soylent Green. Set in 2022, the movie is wrapped in concerns of the early 1970s about overpopulation, dwindling resources, government corruption and corporate malpractice. The plot revolves around NYPD detective Frank Thorn (played by Charlton Heston) investigating the murder of a rich businessman (and his ties to the Soylent Corporation, a company using a mystery ingredient to keep the world fed). Thorn visits the businessman’s deluxe apartment elevated above the grit and grime of dystopian New York. His pad is a technological-utopia. As a playboy of the time, the businessman ‘owns’ a concubine (the sexual revolution having somehow decayed) and also the latest toy: a video game. The game is in fact a real arcade machine from the early 1970s - Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney’s Computer Space (1971) - housed in its original, futuristic-looking fiberglass casing, but in a custom white color for the movie. While the world is falling apart outside the apartment, video games entertain the rich elite. Computer Space offers the perfect escape.

It is now almost 2022, and almost 50 years since Soylent Green, Computer Space, and the first blockbuster video game, Atari’s Pong (a table-tennis simulator released in 1972). Over the past five decades, we’ve witnessed growing climatic problems, the fall of the Soviet Union, a rich businessman become President, and a technological revolution. We are all, today, fully immersed in social media, surveillant society, and Apple products. We live digital lives. And we play digital games: in fact, we play a lot of them. Beyond the reach of baseball or football, gaming is the national pastime of most Americans. And games clearly amount to something far more than simple escape.

Providing interactive experiences far more immersive than film, video games have intimately involved us in elaborate stories of alien invasion and space conflict for some time. They have also used real people and places for their content. My new book Gamer Nation is an exploration of how video games across the last 50 years have depicted one nation and it’s history, life and culture; how video games have depicted America.

As a ‘veteran’ gamer, and someone who actually played Pong first time round, one of the interesting things about researching Gamer Nation was the realization that I’d played many of the titles before, in my own past, and that my views of America as a kid had been colored by early gaming experiences. Working on the book served as a processing of my own ‘gamic memories’: recollections of not just the direct experiences of play, but how play connected with my understandings of the world.

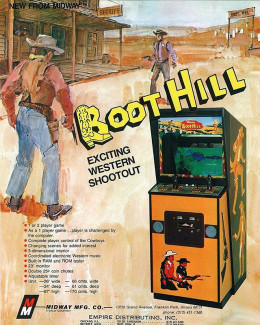

As a somewhat geeky kid, I played Midway’s Boot Hill (1977) - a Wild West-themed title - at the local arcade in the late 1970s: the game triggered my own interest in the American West, and presented (quite erroneously) the frontier experience as a man-versus-man, cowboy-versus-cowboy fight for personal glory. In the mid-1980s, I played Atari’s PaperBoy (1985) - a title about the ‘American everyday’ whereby the player delivered newspapers to suburbia - that taught me about the white picket fences, manicured lawns, and social conformity of the ‘out of town.’

I also encountered games with disturbingly destructive impulses. While working on a chapter tackling depictions of New York City, I revisited a title that I had first played as a child, a game called New York Blitz (1984). Distributed on the Commodore Vic 20 - a beige, weirdly-curved personal computer with limited memory - New York Blitz involved dropping bombs from a descending plane onto a city below, in order to clear a path so that it could land. It was a simple game - focused essentially around timing (when to release the bombs) and strategy (most players knocking out the tallest skyscrapers as first priority). I vividly remembered the game packaging and play screen, and how I understood the ‘American city’ as a colorful, vertical and overpopulated thing thanks to Blitz. However, New York Blitz was, in essence, a game about obliterating Manhattan skyscrapers. In the early 1980s, this seemed problematic but without much contextual meaning; revisiting the title in the 2010s, the game seemed morally offensive, and intriguingly part of a broader cultural trend of imagining New York’s destruction in the late twentieth century (an idea brilliantly explored in Max Page’s book The City’s End). Revisiting Boot Hill, Paperboy, and New York Blitz helped me see how far even the most basic of video games explored the American experience, and how they offered distinctive, and sometimes disturbing, visions of the American past, present, and future.

John Wills is a reader in American culture and history at the University of Kent. He is the author of Conservation Fallout: Nuclear Protest at Diablo Canyon and Disney Culture.