Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Heels, Flats & Ankle Straps: Transitional Shoes In Jane Austen's World

That we have come to associate the emergence of Regency style in North America with Jane Austen is, of course, a tribute to the strength and power of her writing. The first of Austen’s novels to be published in America was Emma, appearing in 1816, within a year of its publication in Britain.[1] It is unlikely that Austen was aware of its release here. When Mansfield Park appeared in 1832, it was published with a title page which stated simply “by Miss Austen, Author of ‘Pride and Prejudice,’ ‘Emma,’ etc. etc.”[2]

Austen’s works offer insights into the material culture of the age. During the heady years of the Early Republic, as Jane Austen’s work was reaching a wider audience, society witnessed changes brought about by the era of Revolutions --the American Revolution, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Empire (known as the Federal or Neoclassical era in the United States and the Regency in England.) Synonymous with social changes was a dramatic transformation in fashion for both men and women at the close of the eighteenth century and into the early nineteenth century. This seismic shift in fashion from richly patterned silk brocades, embellished with metallic threads and spangles, and damask gowns of the Georgian rococo, to the delicate, diaphanous cottons and muslins associated with the columnar alabaster dresses of the Regency, empire or neoclassical/Federal style.

So, too, we can trace a transition in shoes during the Regency period. This revolution in footwear styles was inspired three revolutions: political upheavals that popularized attitudes of republicanism and egalitarianism, an ongoing consumer revolution that provided broader access for middle class peoples to expanding markets, and an industrial revolution that increased mechanization in all aspects of textile manufacture.

Jane Austen came of age amidst these revolutions. In the early eighteenth century, well before her 1775 birth, fashion followed baroque, then Rococo styles--the sinuous plant forms, richly embellished silk brocades and damasks, replete with use of metallic threads and held onto the foot by shoe buckles--were symbols of elite footwear which centered on court life and those emulating it. By Austen’s time, aristocratic trappings such as heels that raised a wearer above others fell out of fashion. Likewise, public engagements, such as the burgeoning concept of shopping, and modes of entertainment such as public dances held at Assembly Halls drove this transformation. Austen captured this transition toward a more romantic mood in her writing, as when she observed in Pride and Prejudice: “To be fond of dancing was a certain step towards falling in love” (Chapter 3).

Austen observed the growing popularity of Regency dances at balls and assemblies. Consequently, dancing—at the Meryton and Netherfield Balls, for example--receive frequent attention in her novels and sets the background for some of the most dramatic exchanges. If it were possible to transport ourselves back to these assembly hall, ballroom, and country estate frolics, we would observe much simpler styles of shoes and slippers that held sway among the younger woman of her novels. Indeed, according to several sources, Austen’s alludes to shoes more often than other fashion adornments, such as reticules (purses).

In the Regency of the Early Republic, assembly halls could be found in urban centers such as Boston, Newburyport, Portsmouth, and Salem, to name just a few representative sites. They were popular locations for large gatherings, and many were specially designed to accommodate dances. As noted by “A Lady of Distinction” in her Mirror of Graces from 1811, the importance of a ball or dance to highlight a lady’s grace, carriage, and dress, could not be overstated. The “Lady” noted:

As dancing is the accomplishment most calculated to display a fine form, elegant taste, and graceful carriage to advantage, so towards it our regards must be particularly turned: and we shall find that when Beauty in all her power is to be set forth, she cannot choose a more effective exhibition.[3]

Dances were exceedingly popular social events that enabled young ladies and gentlemen to become acquainted safely, with a bit of distance, and under supervision.[4] Taking part in a Regency dance required not only a well-versed knowledge of etiquette but also stamina. Regency dances were very energetic, requiring skipping, hopping, clapping and so on. They were generally populated by those between 18 and 30 years of age.

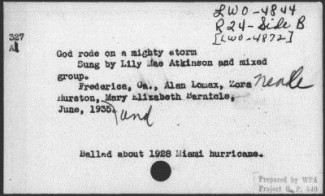

An excellent example can be found in the collections of the Portsmouth Historical Society in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Here, a pair of special occasion shoes provides a glimpse of how one young woman was invited to a dance in the 1780s. Throughout the eighteenth century, Portsmouth was an important secondary seaport and urban center, exchanging the lumber and produce of the Piscataqua River for the manufactured wares of Great Britain. Although not as prominent as neighboring Boston or the rapidly growing towns of New York or Philadelphia, the modest port served as a locus of cosmopolitan consumption for northern New England. A story survives, captured in the silk satin buckle shoes worn by Patty Rogers to a dance in neighboring Exeter in the 1780s. The label pasted into the footbed of the shoe offers a clue to their provenance and their journey. It reads: “Chamberlain & Sons, London.” These delicate shoes probably belonged to Martha (Patty) Rogers (1762-1840), youngest daughter of the Rev. Daniel Rogers of Exeter, and were likely procured in Portsmouth.

In a recent discovery, it appears a pale salmon-hued wallet may have gone with the shoes. In the small silk damask wallet, Curator Emerita, Portsmouth Historical Society, Sandra Rux, discovered a note asking Miss Rogers to a dance. Tucked into the wallet, was a carefully folded message, resembling an origami tulip--a love fold. In it, Mr. Parker asks Miss Patty Rogers to dance with him at a gathering in Exeter. Although not dated, it is probably from mid 1780s – contemporary with the shoes. The cleverly folded small note reads “____ Parkers compliments to Miss Rogers Would be glad to wait on her this evening to dance at Capt True Gilman’s Friday 10 Oclock.” Captain Trueworthy Gilman (b. 1738) lived in Exeter, and Nathaniel Parker (1760-1812) was the likely author. Parker later married Catherine Tilton, while Miss Rogers never wed.[5] However, the London shoes place us at an actual event, in a known place, worn by a young woman who most likely danced at least one dance with Nathaniel Parker. Such is the power of footwear to add depth and specificity to otherwise unremarked or forgotten events in towns and small cities throughout the colonies. While we cannot know what Miss Rogers was thinking that evening, it is possible to speculate that she put on her best ensemble, including stockings, shoes and shoe buckles. That her descendants preserved the shoes and that they ended up in a museum collection reveals an interest in preserving a bit of family history.

In addition to public entertainments, another trend which is quite conspicuous in Jane Austen’s novels is walking and being out of doors--which in turn requires a more substantial mode of footwear. While well-to-do women donned delicate silks and satins for city strolls, something more substantial was required for country living or excursions. No surprise then that the popularity of leather shoes and leather and nankeen half boots increase in the waning years of the 18th century. In discussing her walk in the bad weather with Mr. Knightly, Emma points out that the paths weren't muddy and her shoes didn't get dirty: "Dirty, sir! Look at my shoes. Not a speck on them."

Flats remained popular through the first half of the 19th century. Once heels reappear in the mid-19th century, Victorian shoemakers and their customers embark upon a new episode in fashion, manufacture, and accessibility.[6]

Kimberly Alexander, Ph.D. is Adjunct Faculty in the History Department at the University of New Hampshire (Durham), where she teaches museum studies and material culture. Dr. Alexander has held curatorial positions at several New England museums, most recently as Chief Curator at Strawbery Banke Museum (Portsmouth, NH). Currently the Andrew Oliver Research Fellow at the Massachusetts Historical Society, she is also Guest Curator for the upcoming exhibit, “Fashioning the New England Family,” opening at the MHS in 2018. Her forthcoming book focuses on Georgian shoe stories in early America, tracing the history of early Anglo-American footwear from the 1740s through the 1790s (forthcoming, Johns Hopkins University Press).

[1] Published by Matthew Carey of Philadelphia. For a publishing history of Emma, see: Janeite Deb’s 2015 article https://janeausteninvermont.wordpress.com/2015/12/16/the-publishing-history-of-jane-austens-emma/; for a publication chronology, see http://www.jasna.org/info/works.html

[2] Published by Carey & Lea, in two volumes.

[3] The Mirror of the Graces; or, the English Lady's Costume: Combining and Harmonizing Taste and Judgment, Elegance and Grace, Modesty, Simplicity and Economy, with Fashion in Dress (London: B. Crosby and Co., 1811).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Collection of the Portsmouth Historical Society, John Paul Jones House. The author thanks Curator Emerita, Portsmouth Historical Society, Sandra Rux, for sharing her information on the shoes and wallets. The textile is from c. 1750s. A second wallet, which entered the Portsmouth Historical Society at the same time as the shoes and salmon colored wallet, is a blue silk brocade from late in the eighteenth century. The wallets were likely fashioned from remnants of earlier garments.

[6] Recent exhibitions such as “Fashion Victims” at the Bata Shoe Museum, Toronto, and “Killer Heels” organized by the Brooklyn Museum, delve deeply into the subject.