Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Leviathan Celebrates Melville at 200

2019 was a big year for Herman Mellville. Not only was it the 200th anniversary of Melville's birth, but also the 100th anniversary of the "Melville Revival" - the awakened attention to his work that began in 1919. To mark the double anniversary, the Herman Melville Society’s journal, Leviathan, dedicated four issues over an entire year to material submitted in response to the title “Melville at 200”. The issues included not only a wide array of literary scholarship, but beautiful full-color printing of artistic interpretations of Melville’s texts, and personal essays from scholars and conference attendees. As the final issue of the “Melville at 200” celebration went to press last month, we sat down with editors Samuel Otter and Brian Yothers to discuss the journal’s festive and remarkable year, and how the four commemorative issues came about.

Leviathan is the official journal of the Melville Society. The society website notes that the Melville Society “exceeds the boundaries of the typical single author society” – how so?

BY: Most notably, we are a strikingly international author society. We have substantial groups of members from Japan, the UK, France, Italy, Spain, and Latin America, and we have featured or will be featuring publications on Melville from Iran, Russia, Greece, and Israel/Palestine, as well as the countries and regions noted above. We also are wide-ranging in the approaches we encourage: we include poetry and the visual arts prominently in our issues as well as more conventional scholarly readings of Melville, and we have been energetic in collaborating with digital projects like Melville's Marginalia Online and the Melville Electronic Library. We've also welcomed independent scholars who are working on Melville biography and family and local history.

SO: I would add that sometimes author societies can be too inward-looking, deepening an appreciation of career and biography but not attending to wider contexts and relations. Melville has been at the center of United States literary study since the mid-twentieth century, serving as a lens through which critics have advanced their understanding of aesthetics, history, and politics. The editors of Leviathan seek to draw on this intensity of interest to offer content about Melville that often also speaks to broader issues in literary and cultural studies.

The March 2020 issue of Leviathan is the last in a four-issue celebration of Melville’s bicentennial. How did these special editions come about?

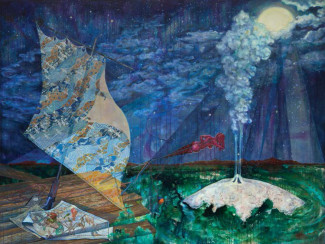

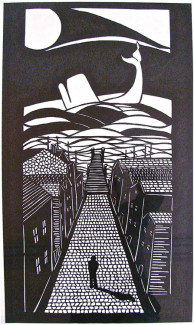

SO: The journal’s editors drafted a call for papers on “Melville at 200” that welcomed contributions on any aspect of Melville’s work, life, times, and reception. Brian and I drafted the call along with the journal’s Book Review Editor Dawn Coleman and “Extracts” Editor Mary K. Bercaw Edwards. (“Extracts” is the section of the journal that reports on Melville-related events in and beyond the Melville Society.) We distributed the call widely and received many submissions. We decided on two strategies for the anniversary issues: offering a roughly chronological series of essays on Melville’s literary career and also featuring in each issue a cluster of essays on a special topic. The essays on Melville’s prose and poetry were invigorated by new approaches to textual scholarship, literary influence, hemispheric and transatlantic history, gender and sentiment, sexuality, temporality, and the relationship between human and non-human worlds. The special topics in the first three issues focused on new artistic responses to Moby-Dick (with a twenty-page color section); the recent completion of The Works of Herman Melville, a monumental editing project that extended over fifty years; and the resonances of Melville’s The Confidence-Man for contemporary U.S. politics. The final issue in the sequence (March 2020) contains a special section edited by Mary K on the Melville bicentennial conference held in New York last June. Dawn and Mary K also developed special content for the sections of the journal they edited. I should mention that one of the essays in the first “Melville at 200” issue (written by Adam Fales and Jordan Alexander Stein and discussed by Brian below) raised questions about the limits of author studies and proposed an alternative of shifting regard to the production, circulation, and reception of books. We welcomed the provocation and the push to reconsider the boundaries of author studies.

BY: I would add that the range of essays across the anniversary issues—from biography to theory, from textually oriented essays on individual works to broad interdisciplinary analyses—helps to capture the range of work that is being done on Melville now. That is, the issues are both large and ambitious themselves and represent the broader ambition of the subfield of Melville studies.

Along with scholarly articles and book reviews, the latest issue includes photos and personal reflections from attendees of the “Melville’s Origins” conference that was held last year in New York. How did you decide to include these personal essays?

BY: Including personal reports on the international conferences from people at a range of career stages and from a range of locales is a longstanding tradition at Leviathan instituted by Founding Editor John Bryant and long-time Associate Editor Wyn Kelley. We find these reports to be valuable in supporting the role of Leviathan as the voice of a developing, growing, and changing community of Melville scholars around the world.

SO: These reports, a recurring feature in the special issues on the Melville Society’s biennial conferences, reflect the participation of international scholars and speakers. In the current issue on the “Melville’s Origins” conference, the report writers hail from the U.S., Argentina, Italy, and England. Recent Melville Society conferences have been held in London, Tokyo, Rome, and Jerusalem.

The March 2019 issue, the first in the anniversary series, includes an extensive section of full color plates – how did such a beautiful collection of artwork get to be in the issue? What challenges did this feature pose to you as editors?

SO: Elizabeth A. Schultz, the author of the double-length essay “The New Art of Moby-Dick” that includes the color-plate section, developed her essay from a lecture she presented at the Tokyo conference in 2015. She is the author of Unpainted to the Last: “Moby-Dick” and Twentieth-Century American Art, the first survey of the extraordinary range of artistic responses to Melville’s book. In her lecture, Schultz discussed the Moby-Dick art produced since her 1995 book, and she widened the scope to include work created not just in the U.S. but across the globe. We invited her to publish an expanded version of her lecture in Leviathan, and things worked out serendipitously so that we were able to feature “The New Art of Moby-Dick” and the color-plate section in the first “Melville at 200” issue. We worked closely with Schultz to determine which of her many illustrations would best appear in color. In the online version of her essay, available via the Johns Hopkins University database Project Muse, all of the images in her essay are reproduced in color. JHUP’s superb production team—Coordinator Myrta Byrum and Typesetter Carey Nershi—did a splendid job of visually arranging the images. In the final “Melville at 200” issue, we were delighted to publish, as a bookend to “The New Art of Moby-Dick,” Robert K. Wallace’s essay on recent Melville-related artworks that have been acquired by the Melville Society Archive in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Wallace’s essay was accompanied by a thirty-page color section.

BY: Melville has been recognized as a distinctly visual author by both literary critics and visual artists. The work that Wallace and Schultz have done over the past three decades has illuminated the ways in which Melville both drew upon the visual arts and inspired them, and Wallace and Schultz have shown how those two facts—the influence of the visual arts on Melville and of Melville on the visual arts—are connected. It’s a great honor for Leviathan to provide a home for major contributions by both of them as part of our “Melville at 200” celebration.

What does a journal like Leviathan, that focuses solely on one author, provide that more broadly aimed ones cannot?

BY: Melville wrote about Emerson "I love all men who dive." There is a depth to which author societies can dive in investigating the confluence of life, work, and context that can only be achieved with a certain intensity of focus. Author societies provide this opportunity for intensity of focus, and the scholarship that comes out of author societies can often have wider impact on scholarly conversations precisely because it is so obsessively focused on a particular body of evidence. One compelling example of this is an article that we published in March 2019 by Adam Fales and Jordan Alexander Stein about Elizabeth Shaw Melville, who was married to Herman Melville. The essay was built around archival research into the Melville family and it drew heavily on the debates among Melville biographers and the work of independent scholars concerned with the Melville, Gansevoort, and Shaw family history, but it also proved to be a highly visible contribution to discussions of gender, authorship, and canonicity in nineteenth-century U.S. literature, and it was discussed in a podcast widely circulated by C19: The Society for Nineteenth-Century Americanists, thus helping to influence conversations beyond the bounds of The Melville Society.

SO: I agree about the value of focus and the value of an expertise that has been honed and altered over generations of scholarship. Using my earlier metaphor, Melville’s works have been a lens through which readers and critics have viewed their times, and those works also have been a mirror that has presented readers with their reflections and unsettled their perspectives. Of course, there are many ways to approach literature, not all of which are author-centric. But grappling with the career of an author, especially a protean writer like Melville, can both clarify and challenge broader inquiries.

How did you come to be a Melville fan and scholar?

SO: During my second semester as a graduate student at Cornell University, I took a Melville seminar taught by Michael J. Colacurcio (now at UCLA), in which he announced that we would be reading everything that Melville wrote except for the marginalia he inscribed in his books. The course was an immersive experience, and I became fascinated by Melville’s verbal imagination, by the ways in which his words, figures, and scenes incorporated and reworked—intimately, palpably, excessively—contemporary debates about race, ideology, and nation. For me, to read Melville closely is to read widely, deeply, and urgently.

BY: I first read Moby-Dick over the summer after my first year in college, when I was working full-time in a bakery frying donuts (with a different sort of oil from that in Melville’s book!) I was especially struck by the ways in which Ishmael was constantly immersed in thought as he was carrying out a range of mundane tasks, and I found myself reading Moby-Dick during my breaks and pondering what I’d read as I fried, finished, and laid out donuts. At that stage in my life, Ahab’s Promethean rebelliousness and Ishmael’s melancholy seemed especially resonant, but I’ve found that different aspects of Melville’s world have come to the fore as I’ve read and re-read his many works. Perhaps surprisingly, the work that first made me think about publishing on Melville was not one of his greatest hits, but rather his 18,000 line poem Clarel, which I read in graduate school and which captivated me with its intricate connections between religious pilgrimage and the nineteenth-century crisis of religious faith and doubt.

With this issue, Sam Otter steps down as Editor, as Associate Editor Brian Yothers takes the helm. Sam, what have you enjoyed most about your time as Leviathan’s editor? Brian, now that the bicentennial celebration is over, what plans are there for upcoming issues?

SO: I enjoyed thinking word-by-word with the writers I edited (we are strenuous editors at Leviathan!) and thus gaining a new appreciation for the qualities of prose in argument; working with younger contributors—graduate students and assistant professors—and helping to advance their careers; and having the world of Melville studies appear in my Inbox.

BY: We have a distinctly transnational bent to our agenda for the next couple years: our June issue will focus on "Melville's England/England's Melville," and we have a special issue on Melville and Spanish America and a special cluster organized by a group of French scholars on the horizon in the near future. We continue to build our connections with the Melville Electronic Library and Melville's Marginalia Online. Our tradition at Leviathan has always been to foster the broadest possible approach to Melville, and this tradition will continue.

Moby-Dick was not well received by critics at the time of its publication in 1851. Today, there are international conferences, marathon readings, podcasts, and more dedicated to the book. Why do you think the work has continued to capture the imagination and passion of modern readers?

BY: Moby-Dick is one of those books that seems to be able to address the questions and concerns of many people across time periods and locations. It deals with questions that connect rather directly to the environment and matters of extinction and climate, to the nature of political power and persuasion, to the problem of evil and the nature of humanity's relationship to divine presence or absence, to questions of knowledge related to what we can know and how we can know it, to the nature of human sexuality and relationships, to our relationships to our bodies and their abilities and disabilities, and to the nature of art, whether in the form of literature, music, or the visual arts. It also is an extraordinarily vivid and funny book. Perhaps most of all, the language is extraordinarily rich and compelling: long ago, R. P. Blackmur said that Herman Melville "habitually used words greatly," and he was right.

SO: The question of Moby-Dick’s recession and resuscitation in U.S. (and now world) culture is fascinating. It involves biography, literary history, the rise of modernism, the development of American literature departments in universities and colleges, the establishment of a literary “canon,” and of course this particular book’s distinctive, unruly verbal energies. I would say two things here. First, the story of Moby-Dick’s initial and utter failure is told repeatedly, but it is not quite accurate. Melville was disappointed by the reception and the sales, but the reviews were mixed and included much praise. Scott Norsworthy, on his meticulous blog Melvilliana, has a long post titled “Moby-Dick widely praised in 1851-2,” in which he demonstrates that conventional narrative of the book’s rejection by mid-nineteenth-century critics is overstated. Second, in addition to the factors I listed at the beginning of this answer, there is something as yet unexplained about the phenomenology of Moby-Dick: the spiraling reflexivity in which a writer pursues a sailor who pursues a captain who pursues the world in one white whale, drawing a proliferating array of readers into its obsessive, unfinished quest.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to take on their first reading of Moby-Dick but may feel intimidated by it?

BY: I always encourage my students to notice the humor, because it tends to deflate the overwhelming sense that one is reading a very serious piece of secular scripture (however true that might be). Moby-Dick is one of the funniest books I have ever read, sometimes in ways that are quite witty and sophisticated, but also in ways that are farcical and scatological, as when Ishmael considers the volume of laxatives needed to relieve a dyspeptic whale. I also encourage them to notice the profoundly touching relationship between Ishmael and Queequeg in the early chapters. The cetological chapters where Ishmael reflects on the anatomy of the whale can be a harder sell, but it's useful to think of them each as a kind of half-serious, half-humorous sermon, where Ishmael takes the whale's body as his text, but then explains something to us about ourselves. Most of all, I think that first-time readers of Moby-Dick do well to slow down and savor the text without trying to jump to too many hasty conclusions about meaning--John Keats's idea of Negative Capability ("being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason") is particularly relevant when reading this book!

SO: Some first-time readers may wish to consult annotated editions of Moby-Dick, such as those prepared by Luther Mansfield and Howard Vincent, by Hershel Parker, and by John Bryant. Or they may wish to consult handbooks such as Bryant’s Companion to Melville Studies, Wyn Kelley’s Companion to Herman Melville, and Robert S. Levine’s Cambridge Companion to Herman Melville. Melville’s words are meant to be heard as well as read: there is an excellent audiobook rendition by Frank Muller, and on the Web readers can find the “Moby-Dick Big Read,” in which each chapter is voiced by a different speaker, ranging from actress Tilda Swinton to former British Prime Minister David Cameron to academics and sailors and preachers. Like Brian, I recommend being receptive to Melville’s verbal exuberance and improvisation, jettisoning expectations, and slowing down the reading experience. The book’s plot is the scaffolding for elaborate verbal patterns that include etymology, philosophy, politics, anatomy, cetology, theology, cartography, allegory, satire, drama, and poetry. James Boswell reported that the writer Samuel Johnson once said about the long novels of Samuel Richardson: “Why, sir, if you were to read Richardson for the story, your impatience would be so much fretted that you would hang yourself.” My advice to first-time readers of Moby-Dick: Don’t be impatient. Don’t hang yourself. Instead, extend yourself. Prepare to be amused, inspired, provoked, and disconcerted. Enjoy.