Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Not Even Past: A Q&A with Cody Marrs

A Q&A with Cody Marrs, author of Not Even Past: The Stories We Keep Telling About the Civil War.

What led you to write Not Even Past?

A lot of it was just living and teaching in the South. The Civil War shades into almost everything here. It’s in the places, the names, the sense of identity. That’s what generated the book: I wanted to connect what I do as a scholar to the everyday world I live in. I wanted to figure out how, why, and when the Civil War became this enduring conflict in American culture. I was curious: Who gets to tell the story of the Civil War, and how does that story change over time? What books have had the biggest impact, and why? I wanted answers, so I read everything I could get my hands on—poems, songs, letters, films, novels, statues, memorials—and then wrote about it.

How has Civil War memory changed over time?

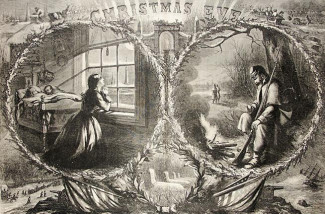

Well, cultural memory never occurs in a vacuum. It’s social and adaptive. So it tends to change as the country changes. For a long time, the most popular memory centered around white fratricide. Brother-against-brother, father-against-son, that kind of thing. That memory is kind of rooted in history: there were some prominent families, especially in the border states, that split up because of the war. But that narrative quickly took on a life of its own, morphing into a larger-than-life mythology, and through the era of segregation it had tons of adherents in both the North and the South. It was taught in schools, pushed by novels, and TV shows, and politicians. The big sea-change occurred during the Civil Rights Movements, which inspired a lot of people to reconsider the Civil War, and it led directly to works like Roots and Margaret Walker’s Jubilee.

What about Civil War memory now, in 2020? Are those same trends at work?

No, this is a unique moment, at least in terms of how people recollect the Civil War. For the first time ever, most people are viewing the war either through the lens of Emancipation or the Lost Cause—as a fight for black freedom or for white supremacy. That’s partly what’s at stake in the struggles over Confederate statues, flags, and memorials. Who gets to lay claim to public space, and everything to which it’s connected (the nation, history, identity)?

What are your favorite stories about the Civil War?

The phrase “Civil War stories” doesn’t usually conjure up exciting associations—maybe The Red Badge of Courage, or a long documentary. But there are tons of well-crafted, illuminating narratives. I love Natasha Trethewey’s Native Guard. It’s the best set of poems about the war from this century. Evelyn Scott’s The Wave is remarkable, too. It’s a richly conceived and lyrically written modernist classic. I’m also a fan of James McBride’s The Good Lord Bird, Terry Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s art, and The Free State of Jones.

And your least favorite?

I’m afraid if I start, I won’t be able to stop… There’s a lot to love in Civil War storytelling, but there’s also a lot to hate. I have a real aversion to the more militaristic accounts of the Civil War. I loathe the novels by Michael and Jeffrey Shaara. They reduce the war’s meaning to a series of strategic decisions. And they’re boring, just pages upon pages of battle-hardened men making tough decisions. It’s like some algorithm translated The Great Man Theory of History into fictional form. And then there’s Gone With the Wind, which is a whole other bag of worms.

You write that “Few events in human history have been revisited so prolifically, or with such astounding passion. Over the past century and a half, the war has spawned about 10,000 memoirs, 6,000 novels, and 2,000 books of poetry, as well as countless songs, statues, speeches, essays, films, paintings, plays, fables, and films.” Why has the Civil War generated so many books, films, and so forth?

From a certain perspective it’s a bit strange, right? Like, why didn’t World War II (which was arguably just as consequential), inspire the same kind of literary output? If there’s one thing I learned in writing this book, it’s that people keep telling stories about the Civil War because it was never settled. The Civil War continues to be a kind of political fault line, the shifting ground upon which everything is build. That’s why there have been so many novels, poems, films, and other types of stories: they allow us to imagine the Civil War to be something other than what it really is, an unsettled conflict that will continue to be refought as long as the U.S. exists.

Cody Marrs is an associate professor of English at the University of Georgia. He is the author of Nineteenth-Century American Literature and the Long Civil War, the editor of The New Melville Studies, the coeditor of Timelines of American Literature, and the author of Not Even Past: The Stories We Keep Telling About the Civil War, now available from Johns Hopkins University Press.