Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

On The Path of Gratitude: East German Climbers in North Korea’s Diamond Mountains

We typically think of East Germans as isolated and sequestered behind the Berlin Wall. There is certainly much truth to this belief. Until 1989, East Germans’ ability to travel was severely restricted by communist authorities. But it is not the whole truth. Throughout their history, some East Germans could and did travel outside the German Democratic Republic (GDR). What happened when East Germans traveled abroad? What did they think of foreign cultures? How did these encounters abroad shape their understanding of state and society back home?

In my new German Studies Review article, “The Path of Gratitude: East German Climbers in North Korea’s Diamond Mountains,” I provide some answers to these questions by exploring two East German mountaineering expeditions to North Korea in the 1980s. Using archival records, press reports, and several recent museum exhibitions which incorporated documentary interviews with the participants, I investigate expeditions which, until now, have been relatively unknown. Doing so helps shed light on the meanings of travel in the GDR, and how perceptions of time and space shaped East German understandings of socialist modernity and dictatorship.

The origins of the expeditions are fortuitous. In 1984, Kim Il-sung, President of the Democratic Republic of Korea, was in the GDR on a diplomatic tour. During a stop in Dresden, he visited the nearby Sächsische Schweiz (Saxon Switzerland), a beautiful region filled with dense forests and rock pillars that climbers had long scaled for sport. During the festivities, Kim was treated to climbers ascending the rock walls organized by the state mountaineering association. Delighted by the display, he invited the climbers to “test their skills” in the mountains of North Korea.

Kim’s spontaneous invitation led to two expeditions to North Korea’s Kŭmgangsan or Diamond Mountains, an area in the southeast of the country, near the demilitarized zone with South Korea. In October 1985, eight Saxon climbers spent ten days in North Korea, and in September-October 1989, another team visited for a month just as the East German state imploded. Authorities hoped the expeditions would nurture closer relations between the two socialist states, while climbers jumped at a rare opportunity to travel and climb mountains no one had ever climbed before.

What is fascinating about the expeditions, and the subject of my article, is how the East Germans experienced their travel abroad and how their foreign encounters provoked reflections about their own society back home. On the one hand, there were intriguing similarities between the two. They both believed they were travelling to a totalitarian state, they both couldn’t resist the opportunity to travel, and they both were unnerved by encounters with Kim’s leadership cult.

On the other hand, there were also significant differences. Although only separated by a couple of years, when the first expedition left, Mikhail Gorbachev had yet to utter the word glasnost, whereas by the time the second departed, Poland had a noncommunist prime minister. The dramatic changes unfolding in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s thus framed how the East Germans experienced North Korea, and how they reinterpreted their own society back home.

What was especially noticeable to me was how temporal perceptions affected how the climbers understood their foreign experiences. When the first expedition left, they assumed they would return to a state as it always had been, and this understanding of East German stasis conditioned their experiences abroad. For them, the North Korean expedition was an exceptional interruption in the normative flow of time that needed to be appreciated since it was unlikely to be repeated (or perhaps, appreciation might lead to another). The hardest route climbed they called the Weg des Dankes (The Path of Gratitude) because, as the top climber Bernd Arnold put it, “you have to show gratitude for a journey like that, and this was how we did it.”

By contrast, the second expedition, traveling amid the dramatic events unfolding on East German streets in autumn 1989—but whose conclusions remained unknown—experienced North Korea much differently. Encountering prison camps in the jungle and witnessing the construction of the Ryugyong hotel in Pyongyang, these experiences provoked anxieties about the GDR. For one climber, North Korea convinced him to emigrate upon return because he had just witnessed East Germany’s future; and it was, “[l]ike something out of a film about a terrible future.”

These differences illustrate how domestic understandings shape foreign experiences and vice versa. But more importantly, they also indicate how temporal perceptions helped structure the East German dictatorship. Whereas members of the first expedition embedded their experiences in a framework of eternity and gratitude which buttressed the authority and power of the ruling communist party, those travelling a few years later saw state socialism’s temporal imaginaries disintegrating; dissolution allowing them to envision previously unimagined futures. And the rapid evolution from permanence to transience suggests a revolution in temporalities also helps to explain the collapse of East Germany in 1989.

Jeff Hayton (jeff.hayton@wichita.edu) is an associate professor of History at Wichita State University. He is the author of Culture from the Slums: Punk Rock in East and West Germany (Oxford, 2022) and editor, along with Scott Harrison and Katharine White, of Socialist Subjectivities: Queering East Germany under Honecker (Michigan, 2025). He’s currently writing several books on mountains and mountaineering in German history.

“The Path of Gratitude: East German Climbers in North Korea’s Diamond Mountains” will be published in the May 2025 issue of German Studies Review.

Images, in order of appearance:

1. The ‘granite giants’ of the Kŭmgangsan (Diamond Mountains) in North Korea, 1989. Courtesy: Ute Friedrich

2. Petra Winter (left) and Ute Friedrich (right) with their North Korean chaperones, 1989. Courtesy: Ute Friedrich

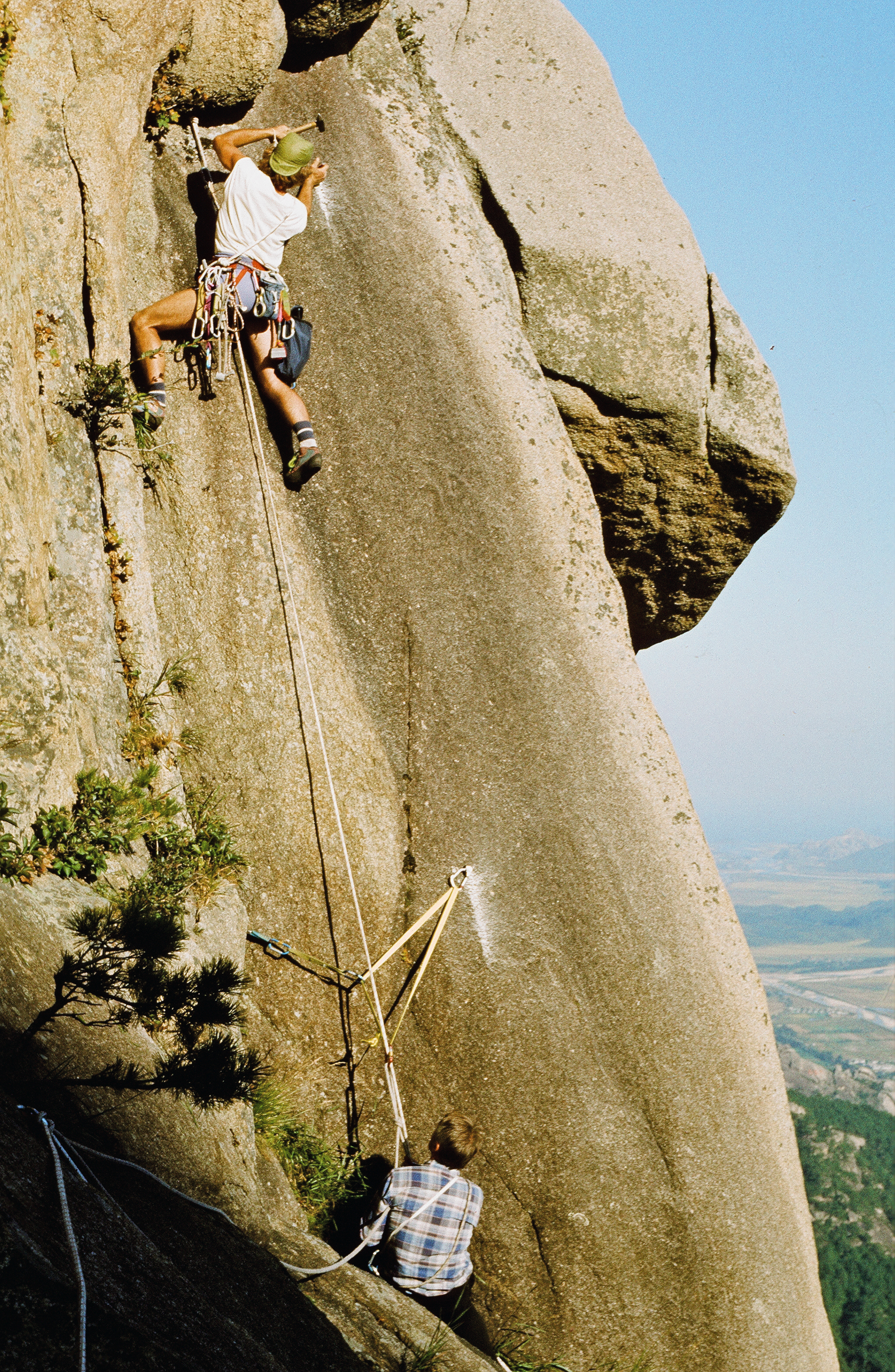

3. Alexander Adler drives in a safety piton, 1989. Courtesy: Ute Friedrich

4. Joachim Schindler (far left) and Bernd Arnold (far right) during the first East German mountaineering expedition to North Korea, 1985. Courtesy: Joachim Schindler