Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

“Perfectly Polite and Agreeable”: Anglo-American Encounters on the Far Side of Jane Austen’s World

In June 1812, just after Jane Austen had completed her inaugural novel, Sense and Sensibility, the US Congress astonished Britons by declaring war on their nation. Through the War of 1812, Austen would continue to publish, producing some of her best-known works: Pride and Prejudice in 1813, Mansfield Park in 1814, and Emma in 1815, though she would write nothing about Americans.

As Lauren Gilbert observes, in an article entitled, appropriately, “Unrequited Love,” “Jane Austen had little to say about America, and that little was not good.” A letter of September 2, 1814, noted, “I place my hope of better things on a claim to the protection of Heaven, as a Religious Nation, a Nation in spite of much Evil improving in Religion, which I cannot believe the Americans to possess.” Americans have since shown more love for Austen than she showed them. Yet, Austen’s readers may have thought that the atmosphere of gentility and politeness that she explored in her wonderful novels aptly conveyed the relationship between the two countries—encounters of “pride and prejudice,” but little “sense and sensibility.”

It was far from the English countryside of Steventon, Oxford, and the imagined Pemberly, in the waters sailed by her brothers Admiral Francis and Real Admiral Charles and her characters Captain Frederick Wentworth, Admiral Croft, and Midshipman William Price, that encounters between John Bull and Brother Jonathan played out. Their rhetoric described the War of 1812 as a defense of national honor, political legitimacy, military might, and the like. But, placing these incidents within Jane Austen’s world of “polite and agreeable” manners enlarges our appreciation of the Anglo-American relationship during Austen’s lifetime and beyond.[1]

In the Regency era, gentility was like the seas themselves: The rules of “civility” and “politeness” could carry afar one who knew how to navigate them, but they were barriers to those who had not mastered their mysteries. As Americans and Britons encountered each other, in Cape Town or Calcutta or Canton, in Bombay or Batavia or Bencoolen, gentility served as the oil that smoothed roiled waters and a litmus test of appropriate behavior. This concern fills the logbooks of American ships throughout the period.

At times, their correspondence struck the appreciative tone of Edmund Fanning’s log for the Betsey in July 1797:

At 6 p. M. were fired upon, and brought to, by the English frigate Romulus, from which ship an officer boarded the Betsey, and commenced examining her papers and men; having gotten through with this, he took leave, saying, as soon as we pleased, we might sail, and wished us a fortunate voyage.Three years later, as his Betsey anchored at Pernambuco, Fanning again recorded, “The reception was very polite and courteous.”[2] At other times, captains reported small acts of “impoliteness,” as in the log of the Grand Turk out of Salem for 30 June 1792, which observed, “A ship passed us that hath been in sight 6 days—an imperious Englishman and would not speak [to] us.”[3]

* * *

This dance of civility emerged in the first year of American independence, in the first voyage to Asia, in the first contacts with Britons on the far side of the world. The 1784 log of the Yankee merchantman, the Empress of China, and the journals of her supercargo, Samuel Shaw, tell the story: As a new nation, as the “new people,” as they were known from Constantinople to Canton, the officers and crew were preoccupied with matters of respect, virtually fetishizing “politeness” and “civility.” They knew well the sentiment of John Adams, who observed of Britons: “They have been taught from their cradles to despise, scorn, insult and abuse us. . . . Britain will never be our friend, till we are her master.” And, especially on the far side of the world, where they sailed in unfamiliar seas and traded in exotic ports, they wondered about “the reception our citizens would meet.”[4]

Shaw was concerned with “the reception our citizens met” at Canton, more so that of the European community there than the Chinese, and he noted with some pride that John Bull had not been “behindhand.” Even the head of the English factory assured him, “As soon as it was known . . . that your ship was arrived, we determined to show you every national attention.” As to the war, the erstwhile enemies strove to make amends, and America’s unofficial consul described the English overtures in glowing terms: “On board the English [ships], it was impossible to avoid speaking of the late war. They allowed it to have been a grave mistake on the part of their nation, were happy it was over, glad to see us in this part of the world, hoped all prejudices would be laid aside, and added, that, let England and America be united, they might bid defiance to all the world.”[5]

* * *

Not all encounters at sea were “perfectly polite and agreeable,” however, and Jane was well aware of conflicts between the cousins. One of my favorite stories touching civility at sea took place in waters just off England:

In June of 1793, when Jane was just 17, a twenty-four-year-old American seaman named Edmund Fanning (1769-1841) found himself off the Scilly Islands. The opening salvos of the Wars of the French Revolution had caught up to the New York vessel Portland, under Captain Thomas Robinson and First Officer Fanning. As the Portland hove to, there ensued a remarkable conversation between Captain Robinson and the cutter’s commander.

Advised of the Portland’s cargo and destination, Pennsylvania flour for the French port of La Harve, the British commander ordered her captain to “come immediately on board of me with your papers.” Instead, Captain Robinson serenely replied, “if you wish to examine my papers, you must come on board my ship, for I cannot consent to leave her.” Infuriated with Robinson’s defiance, the cutter’s commander bellowed out, “You d____d Yankee, hoist out your boat this instant and come on board, or I will sink you!” Robinson would not be deterred, however, and in a studied, genteel voice, responded, “I understand my duty too well, and your vulgar threat will not sway me from it!” The cutter now trained her guns on the Portland, “followed by a threat,” Fanning tells his readers, “couched in the same courteous language” the British commander had hurled a moment before. Still, Robinson coolly advised the officer, “he would not . . . obey the order; more especially as it contains so much of the fine feelings of a gentleman and officer under the flag of His Britannic Majesty.” Ultimately, the American, “ever careful of the lives of his men,” saw no choice but to surrender the Portland, another prize to unbridled European hubris. However, he had made his point, one that with perhaps more deliberation he had certainly crafted for an audience back home, that Americans were not a race of barbarians, but instead refined, sophisticated, and, indeed, equal to the polite society of England.[6]

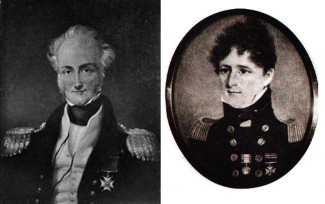

The British officer could have been Jane’s brother, Charles, or one of his fellow officers. He was on patrol during these years in North American waters from January 1805. In fact, Charles’s prizes included four American ships. As historian Sheila Johnson Kindred observes, “Charles’s service at sea … primarily included cruising for trade protection, transporting troops, and searching American ships for British deserters. . . . Charles and his brother officers were alert to the chances of apprehending vessels as naval prize and excited by the prospect of enriching themselves with prize money.”[7]

What would Jane Austen have made of the exchange between British and American officers at sea, beyond the shores of civilization, but supposedly within the confines of civility?

On the 200th anniversary of Austen’s death (July 18), JHUP offers two titles that can shed light on the issue. Janine Barchas’s 2012 study, Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity and Devoney Looser’s just released The Making of Jane Austen are must reads, not just for Austenistas, but also for scholars interested in broad matters of gentility and politeness in the early modern world.

Dane A. Morrison is a professor of early American history at Salem State University. He is the author of A Praying People: Massachusett Acculturation and the Failure of the Puritan Mission, 1600–1690 and True Yankees: The South Seas and the Discovery of American Identity and the coeditor of Salem: Place, Myth and Memory and the World History Encyclopedia, volumes 11–13: The Age of Global Contact.

[1] Samuel Haynes, Unfinished Revolution: The Early American Republic in a British World (Charlotte: Virginia, 2010); Kariann Yokota, Unbecoming British: How Revolutionary America Became a Postcolonial Nation (New York: Oxford, 2011); and Daniel Kilbride, Becoming American in Europe, 1750-1860 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2013); Nicholas Rogers, The Press Gang: Naval Impressment and its Opponents in Georgian Britain (New York: Continuum, 2007); Denver Brunsman, The Evil Necessity: British Naval Impressment in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World (Charlotte: Virginia, 2013); and J. Ross Dancy, The Myth of the Press Gang: Volunteers, Impressment and the Naval Manpower Problem in the Late Eighteenth Century (Woodbridge, ENG: Boydell, 2015).

[2] Harriett Low, Journal, 1829–1834, 9 vols., Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, 1 February 1833.

[3] Quoted in Robert E. Prince, The Log of the Grand Turks (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1926),

124.

[4] Samuel Shaw, The Journals of Major Samuel Shaw, the First American Consul at Canton, ed.

Josiah Quincy (Taipei: Ch’eng-Wen, 1968), 43 and 200.

[5] Shaw, Journals, 181.

[6] Fannin Edmund, Voyages Round the World; with Selected Sketches of Voyages to the South Seas, North and South Pacific Oceans, China, etc., Performed under the Command and Agency of the Author. Also, Information Relating to Important Late Discoveries; between the Years 1792 and 1832, Together with the Report of the Commander of the First American Exploring Expedition, Patronised by the United States Government, in the brigs Seraph and Annawan, to the Southern Hemisphere (New York: Collins & Hannay, 1833); 31-34.

[7] Sheila Johnson Kindred, “The Influence of Naval Captain Charles Austen’s North American Experiences on Persuasion and Mansfield Park,” Persuasions, 31 (2009): 115-129.