Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Personal Accounts of Sailors are Unique Entry Points into the Civil War

A reviewer of my just released fourth book, Faces of the Civil War Navies, asked me a question that I found difficult to answer.

What’s your favorite story?

The question seems simple and straightforward on is face. But I’ve spent the last four years immersed in the personal narratives and wartime portraits of about 80 sailors. This is no softball question for me. It’s a fastball in the last inning of the World Series.

I find the question a challenge because each personal account contains details that can surprise, fascinate and inspire. The stories and photos remind me that the war

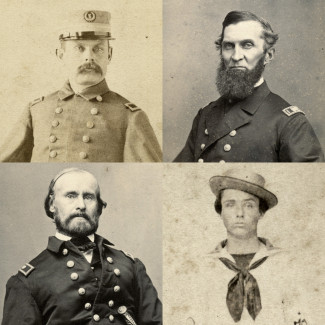

Consider Nathan Hopkins, a seaman on the Union frigate Minnesota stationed along Virginia’s James River in 1864. He and two of his comrades were granted permission to leave the vessel and stretch their legs. The trio ran into Confederates, and in this moment Hopkins learned his two buddies were bounty jumpers looking to escape. For Hopkins, the episode ended in a trip to Andersonville.

Then there is the experience of Eugene Brown. An engineer in the Confederate navy, he was part of the crew of the schooner Archer that eased unobserved into the harbor of Portland, Maine, one evening in late June 1863. The next morning, he and his crewmates captured the Caleb Cushing, a state-of-the-art U.S. revenue cutter. But Brown could not operate the newfangled engines and what might have been one of the greatest navy stories of the war ended in capture about 20 miles outside the harbor. This was major news across the country, but was quickly overshadowed by the Battle of Gettysburg.

Oh, and there is the account of poet Henry Howard Brownell. One of his patriotic poems caught the attention of Rear Adm. David Farragut, who invited Brownell to join his staff with the rank of ensign. No matter that he had no military training. Soon, Brownell found himself on the deck of Farragut’s flagship Hartford during the Battle of Mobile Bay. In the thick of the action, with enemy shot and shell tearing the wood ship and its crew to shreds, Brownell is observed standing on deck quietly jotting down his impressions, cool as the most seasoned veteran.

And how about George Work? Old enough to be the father of most of the sailors in the ranks, he had made a small fortune on Wall Street. Most men of his age and wealth did not join the military. But he did, and was assigned to one of the new ironclad monitors, the Tecumseh, as paymaster. The vessel took the lead during Farragut’s attack at Mobile Bay, and in the opening moments struck an underwater mine. The explosion sent her to the bottom of the bay in about 30 seconds. A large number of the crew was lost, including Work. His remains were never recovered and are presumed interred in the Tecumseh. His navy service ended after only months in uniform.

Paymaster Work and the others featured in the book are unique entry points that humanize the Civil War. They participated in four bloody years of fighting that drained our nation of men and materials on a scale not equaled before or since. “The history of the Civil War is the stories of its soldiers,” is a phrase I’ve used many times in the past to summarize my work. After my journey with Faces of the Civil War Navies, I’ve added an addendum to this statement: “—and sailors.”

Photo credits: Clockwise from upper left: Eugene Brown, collection of Gerald Roxbury; George Work, author’s collection; Nathan Hopkins, Jerry & Teresa Rinker Collection; Henry H. Brownell, author’s collection.

Ronald S. Coddington is assistant managing editor at The Chronicle of Higher Education, editor and publisher of Military Images magazine, a contributing writer to the New York Times’s Disunion series, and a columnist for Civil War News. His trilogy of Civil War books, African American Faces of the Civil War, Faces of the Confederacy, and Faces of the Civil War, all published by Johns Hopkins University Press, combine compelling archival images with biographical stories to reveal the human side of the war.