Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Before Queer Theory: Victorian Aestheticism and the Self

I wrote Before Queer Theory: Victorian Aestheticism and the Self to account for an experience that I think is fairly common, but which has not often been described in academic queer theory: the act of discovering an empowered, socially oppositional sense of queer selfhood in and through art.

Like many gay teenagers, I was shy, introverted, and bookish. At that time, reading about being gay seemed much safer than actually having to do anything about it. Coming of age in the 1990s, most of the depictions I encountered were clichéd and one-dimensional: noble and tragic AIDS patients, sexless best friends, victims of hate crimes, protagonists of maudlin “coming out” stories, bogies of the religious right, targets of crude locker-room humor—in all cases, definitive outsiders to the fabric of social life. The thought that I might count myself among that group did more than fill me with fear. I could not conceive how my internal perception of myself as a complex human being was in any way related to these radically diminished figures. How could I be that?

Over many months spent hidden in a corner of my local library in rural California, afraid to check out any books for fear of the looks I might receive at the counter, I read the writings of any queer author I could find: Oscar Wilde, Radclyffe Hall, James Baldwin, Rita Mae Brown, Armistead Maupin. Through these readings, I gradually came to see myself differently. A growing apprehension that I was, indeed, very much like the characters in these books contended with an appreciation of the beauty with which these authors portrayed queer lives. Out of this tension there arose a tentative yet meaningful sense of self that stood apart from negative cultural messages. Although I was aware that I was part of a homophobic society that placed practical limitations on what I could do and who I could be, I also realized for the first time that choosing not to follow the narratives of development that society presents as natural and inevitable was both possible and, potentially, wonderful. Through these artworks I discovered that I could, within limits, define for myself what my life would be. I consider this not only the moment when I finally accepted my sexuality, but also the birth of my critical consciousness. If what the dominant culture presented as the truth of queer identity had almost no relationship to my own newly developed sense of self, then what other supposed truths needed to be questioned?

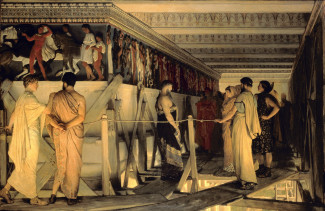

Queer theory tends to be skeptical of the notion of selfhood, for very good reasons. One of the most powerful lessons of foundational writings by Michel Foucault and Judith Butler is that often what feel like the deepest truths of our psyche is actually nothing more than the expression of internalized social norms. Yet in Before Queer Theory, I establish that queer Victorian aesthetes such as Walter Pater, Oscar Wilde, Vernon Lee (Violet Paget), and the two women who wrote poetry under the pen name “Michael Field” (Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper) anticipate and respond to such skepticism by portraying art as a creative realm where the rules and logic that govern everyday social life are partially relaxed. The aesthetes realized that art “projects above the realities of its time a world in which the forms of things are transfigured,” to quote Pater, and creates a space where queers can reflect critically on their social conditions and envision new modes of seeing, forms of thinking, and ways of living. This allows them to cultivate a sense of independent self-direction through opposition to repressive social norms. I argue that Victorian aesthetes anticipated many of queer theory’s most powerful insights regarding the nature of subjectivity, literary style, performativity, history, and the notion of “queering” an artwork, but that they did so with the goal of winning for queer people a measure of personal autonomy in a homophobic world.

Despite being more than a century old, the insights of the aesthetes have yet to take hold in contemporary discussions of sexual identity. Even politically progressive people assert that some people are biologically “born this way,” implying that, if one had a choice, one would inevitably not want to possess desires that put one at odds with what society considers normal and natural. As Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick has stated, it continues to be truth that “[t]he number of persons and institutions by whom the existence of gay people—never mind the existence of more gay people—is treated as a precious desideratum, a needed condition of life, is small.” In Before Queer Theory, I assert that the aesthetes created an important early version of exactly this sort of radically queer-affirmative discourse. They powerfully and rigorously articulate a position rarely uttered in either Victorian or modern culture: that one might want to be queer, when being so provides the opportunity to be part of an emancipated artistic vanguard, charged with the self-appointed task of reimagining how life might be lived.

Dustin Friedman is an assistant professor in the Department of Literature at American University. He is the author of Before Queer Theory: Victorian Aestheticism and the Self.