Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Reading Disability in a Pair of Eighteenth Century Shoes: Mary Wise Farley, 1764

Everyday life for many in early America involved endless rounds of backbreaking labor, grueling travel into dense forests, across frozen rivers, or through putrid swamps, and the ever-present risk of illness, accident, and injury. How did early Americans cope with physical disability? The research for my recent book, Treasures Afoot, led to the examination of dozens of pairs of shoes, many that revealed a variety of difficulties associated with feet-bunions, overpronation, hammer toes, and the accommodation of expanding feet due to pregnancy or illness.[i] The records and account books of New England cordwainers even report the use of cork shoes to relieve gout, which frequently begins in the foot.

A rare surviving example of how one woman addressed her disability may be found in the nuptial footwear of an eighteenth-century New England bride. Mary Wise Farley’s wedding shoes reveal that she was “lame.”[ii] It appears that she never wrote down her story, but her extant shoes give her a voice—if we can take the time to listen. Indeed, were it not for the survival of her shoes, very little would be known about her.

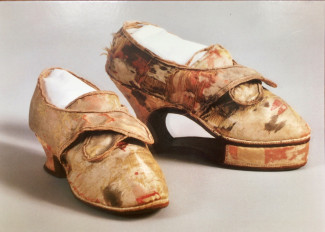

Image: Mary Wise Farley’s brocaded silk wedding shoes, c. 1764. The shoes were attached to the foot by shoe buckles. Courtesy, Ipswich Museum.

According to files in the Ipswich Museum, the silk brocade shoes belonging to Mary Wise (1741-1792) were worn at her wedding to Nathaniel Farley (1731-1809) in 1764 or early 1765 (their intention to marry was published and dated 17 November 1764).[iii] She was in her early twenties. This was her first marriage, while it was Nathaniel's second. Mary was born and died in Chebacco (now Ipswich, Essex County, Massachusetts). Her first child was a son named Daniel, born on 26 September 1765. Her husband had a son, also named Nathaniel, by his first wife, Elizabeth Cogswell. Mary's shoes were passed down through the family and are now in the care of the Ipswich Museum.

At first glance, it is clear these shoes are unusual. One shoe has been built up at the sole and heel to accommodate the difference in the length of the bride's legs. The height of one of the heels is 1.25 inches and the other is 2.75 inches, indicating that the bride was likely disabled. A special wood and leather platform was added to one shoe. Using the same-quality materials that constitute the shoes' textile, special care was employed to match the front portion of the addition. It is neatly, meticulously sewn.

More study, however, is needed regarding the construction of Mary Wise Farley's shoes, including their wood and leather superstructure, method of construction and attachment, and interior details. While the maker is unknown, certain details including the style, the quality of material, and finishing details indicate a London cordwainer, bespoke order, or an especially skilled colonial American shoemaker.

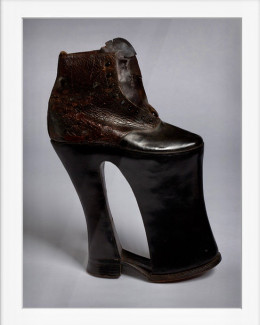

Image: Victorian leather orthopedic shoe, which is probably much more typical in the 18th and 19th centuries than Mary Wise Farley’s carefully crafted wedding shoes. Courtesy, Black Country Living History, UK.

These brocaded silk buckle shoes were not meant to be hidden. Mary, who was from comfortable circumstances but not part of "the quality," nonetheless celebrated her wedding in the elegant style of the times. Although perhaps difficult to visualize today, due to the shattered and shredded silk of the textile, when new, the silk would have caught glints of light as she walked, as would the glittering buckles with which she attached her shoes. In her selection of fashionable footwear for her wedding, this particular bride was able to take agency—even if just for this special day—in a world that frequently offered little to women, regardless of their social, economic or physical condition.

Historian Kimberly S. Alexander, a former curator at the MIT Museum, the Peabody Essex Museum, and Strawbery Banke, teaches material culture and museum studies at the University of New Hampshire. She is the author of Treasures Afoot: Shoe Stories from the Georgian Era.

Image: An engraving of a man with gout. Courtesy of the Historical Division, The Cleveland Health Sciences Library.

[i] For information on various foot conditions, see: Foot Anatomy: Your Amazing Feet https://www.everydayhealth.com/foot-health-pictures/common-foot-problems.aspx

For writings on disability generally, see: TURNER, DAVID M. DISABILITY IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND: Imagining Physical Impairment. S.l.: ROUTLEDGE, 2017; K. Ott, ‘Disability things: material culture and American disability history, 1700–2010’, in S. Burch and M. Rembis (eds), Disability Histories (Urbana, 2014), 122; ‘Disability 1660-1832’ in https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/disability-history/1660-1832/; “‘Confined to Crutches’: James Logan and the Material Culture of Disability in Early America,” Pennsylvania Legacies, Vol. 17, No. 2 (Fall 2017): 6-11.

For teaching, see: Nicole Belolan “Over-the-hill canes and ideal bodies: teaching disability history as public history” https://ncph.org/history-at-work/teaching-disability-history-as-public-history/

[ii] On the term “lame” and eliminating the use of ableist language, see: FWD (Feminists with Disabilities): http://disabledfeminists.com/2009/10/12/ableist-word-profile-lame/, and Rebecca Strout, https://li.st/RStrout/list-of-ableist-language-and-alternatives-2QawoEjJokDWESGkqU20Na

[iii] Ipswich Museum Accession number, 1900.023.001a-b