Reading Jane Austen with Vladimir Nabokov

Guest post by Janine Barchas

Great writers are great readers. And nothing dials up the magnification on a book like the green-eyed gaze of a fellow author.

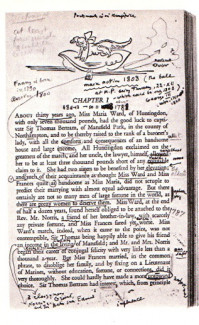

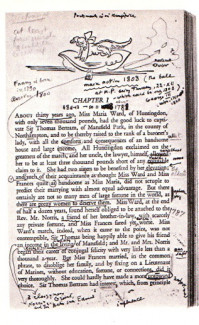

In 2014, many Jane Austen fans have been rereading what is arguably her darkest and most difficult novel in celebration of Mansfield Park’s bicentenary. One unique copy of that novel, formerly owned by Russian-born American novelist Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977), enables the rereading of one great novelist over the shoulder of another.

Nabokov’s landmark lectures, however, were impeccably edited by Fredson Bowers and published as Lectures on Literature in 1980. The lectures remain an entertaining read, especially if you like your literary criticism dosed with equal amounts of snark and pedantry. But perhaps Nabokov’s keenest insights into Austen’s style may be gleaned from the raw marginal annotations in his copy of Mansfield Park, made during multiple re-readings over many years of teaching.

Nabokov’s copious annotations taught me much about Austen’s unique handling of temporal and spatial distance. In the margins of his copy and on separate sheets of notepaper, Nabokov draws charts, maps, and diagrams, makes lists of dates and names, and calculates distances, incomes, or ages from the numerical crumbs dropped by Austen. Guided by her descriptions, he maps the grounds at Sotherton Court, sketches a barouche to determine the spatial arrangements of the characters in a carriage, and lays out the rooms of Mansfield with architectural confidence. He also sketches maps of England, including a small one in the top corner of his copy’s opening page, noting the locations of both real and imaginary places mentioned in the text, such as “Portsmouth,” “Huntingdon,” “Hampshire,” “London,” “MP.” He triangulates the presumed location of Mansfield Park from the stated distances to real-world cities: “120 m” between MP and Portsmouth, “50” from Portsmouth to London, and “70 m” from London to MP. He circles her alliterations and underlines important phrases. This is what happens when one great novelist takes another seriously.

Nabokov calculates from specifics in the story that the year of the “main action” is “1808,” explaining in his lecture how he arrived at this date: “The ball at Mansfield Park is held on Thursday the twenty-second of December, and if we look through our old calendars, we will see that only in 1808 could 22 December fall on Thursday.” The fact that Nabokov bothers to locate Austen’s “Thursday” in real time implies trust. He believes her words worthy of attention and assumes she is in complete control of all aspects of her story—even details that others might brush off like the colorful confetti of a casual realism. In fact, Nabokov warns against any lazy comparisons to “what book reviewers, poor hacks, call ‘real life’ ” and insists that his students read Mansfield Park on Austen’s terms: “There is no such thing as real life for an author of genius: he must create it himself and then create the consequences. The charm of Mansfield Park can be fully enjoyed only when we adopt its conventions, its rules, its enchanting make-believe.”

Betrayed by his pronouns, Nabokov, lecturing in the unenlightened idioms of the 1950s, was guilty of some exasperating condescension, too. Imagine him delivering this from the podium to an assembly of students: “Miss Austen’s is not a violently vivid masterpiece as some other novels in this [lecture] series are. Novels like Madame Bovary or Anna Karenina are delightful explosions admirably controlled. Mansfield Park, on the other hand, is the work of a lady and the game of a child. From that workbasket comes exquisite needlework art, and there is a streak of marvelous genius in that child.” Sigh.

I believe his own minute annotations in Austen’s novel best protest his chauvinism. A committed lepidopterist and naturalist, Nabokov even underlines and questions the varieties that Austen assigns to her trees, annotating in pen, then pencil, her scattered references to specific types of fruits, plants, and landscape features. Nabokov’s annotations may be deeply personal, marking his peculiar curiosities, but their quantity insists upon his professional assessment that all of Austen’s details are meaningful and worth pursuing.

Nabokov’s retro pomposity aside, his annotations taught me to look closer and harder—to read Austen with more effort. Luckily, today’s digital toolkit makes it easier to test the interpretive benefits of a Nabokov-style approach, allowing individual readers to track Austen’s clues about distances, dates, allusions, and all manner of details for themselves.

In my classroom, I urge my students to “read like Nabokov” and challenge them to imitate his aggressive style of annotation in their own copies (yes, the argument for teaching with paper books is implied here). For my own part, the marginalia and underlinings in my teaching copy of Mansfield Park, a Norton paperback, do grow every year. And every year I learn just a little bit more about this great novel.