Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Reading the Market in the Age of the Flash Crash

On 6 October 2016 the British pound fell 6 per cent in the space of just a few minutes of electronic trading. Just as quickly, sterling regained most of its value, but the scare caused the new Chancellor of the Exchequer to warn that the road to Brexit might well be a bumpy ride. This is only the latest “flash crash” to have hit the world’s currency and stock markets, involving transactions whose speed is measured in millionths of a second. Although some explanations have focused on so-called fat finger trades (in which a rogue order keyed in by the clumsy digits of a broker), it seems increasingly likely that most flash crashes are caused by one of the computer algorithms that now underpin most trading going awry, triggering an escalating spiral of panicked transactions that happen at a pace far faster than any human can detect or prevent.

In this case, one theory is that an algorithm reacted to a news article and the inevitable accompanying Twitter conversation seeming to suggest a “hard Brexit,” which in turn caused other algorithms to begin dumping sterling. In this science fiction scenario, it is as if the market has taken on a mind and life of its own, as computers trade in a frenzied fashion with other computers. If anyone is watching the market now, it is an artificial intelligence. We mere humans are baffled by-standers left to pick up the pieces as we struggle to make sense of these cataclysmic events. Flash crashes present a new chapter in the long history of stock market watching, whose origins in the Gilded Age I explored in Reading the Market.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, only one percent of Americans were invested in the stock market. Yet in the Gilded Age there was an explosion of popular fascination about the market, with a welter of novels, short stories and magazine articles fuelling the emergence of a daily culture of market watching. In short, Americans become emotionally invested in the stock market long before they came to hold actual investments. This imaginative engagement with the market was enabled by new genres of financial information such as the financial pages of the newspapers and popular financial advice manuals, as well as by the hundreds of bucket shops that sprouted up around the country. (Bucket shops were fake brokerages in which customers in effect bet against a rise or fall in market prices, allowing ordinary folk a cheap and vicarious taste of the excitement of the official stock market).

Whereas earlier in the nineteenth century reports on stocks and shares had largely been confined to specialist publications for market insiders, in the Gilded Age this information came to matter to the general public, who anxiously began to watch the market as a barometer of national mood and personal fortune—even if they didn’t actually own any shares.

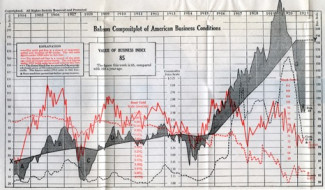

This obsessive form of market reading was made possible in large part by the invention of the stock ticker in the late 1860s, which meant that stock prices could now be transmitted simultaneously over the telegraph wire to the nation, and even the entire world. Before this, the market was an actual place, and could only be viewed in person from the public gallery of the stock exchange. But from the 1870s onwards “the market” became a placeless abstraction that was conjured up in the minds of all those avidly reading the endless fluctuations of prices that came over the ticker, and, from the turn of the century, the peaks and troughs of stock market graphs that abstracted those price movements into seemingly intelligible patterns.

Those now familiar sublime mountainous landscapes—with their heart-dropping precipices—were of course used to illustrate and explain this week’s sterling flash crash. But they also serve to naturalize such events, making the market seem like an impersonal, self-regulating machine that is prone to periodic glitches, and which operates without regard to human oversight or even understanding. Although algorithmic High Frequency Trading (HFT) presents a significant new twist in the story of the stock market, it is also merely an intensification of a process that began in the Gilded Age, namely the emergence of the taken-for-granted wisdom that the market knows best. By looking back at the history of the emerging representational technologies of modern financial capitalism, we can help to de-naturalize the myth of the rational market. And in doing so we can begin to reclaim the democratic insistence that the market should not be left to professionals—and certainly not machines manically trading with other machines in a hall of mirrors.

Peter Knight is a professor of American studies at the University of Manchester. He is the author of Conspiracy Culture: From Kennedy to The X Files and The Kennedy Assassination. His latest book is Reading the Market: Genres of Financial Capitalisim in Gilded Age America.