Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Satire: From Alexander Pope to SNL

When Andrew Benjamin Bricker watches Saturday Night Live or the Jordan Peele film Get Out, he thinks of the eighteenth century. An Assistant Professor in the Department of Literary Studies at Ghent University in Belgium, Bricker recently published "After the Golden Age:Libel, Caricature, and the Deverbalization of Satire" in the Spring 2018 issue of Eighteenth Century Studies. Those modern comic works show the evolution of satire popularized in the eighteenth century by writers like Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope. Bricker joined us for a Q&A about his article.

Why is the study of satire in the 18th century such a rich topic?

So it’s easy to say that eighteenth-century satire is such a rich topic because it was so important and central to this period and its modes of public discourse. But part of the reason I find eighteenth-century satire so interesting is because it in many ways helped to create the style of so much of the stand-up, sketch comedy, and parody news we have today. Whether it’s unflattering impersonations of Donald Trump on Saturday Night Live or really intelligent, cutting and funny allegorical evaluations of race in America, like Jordan Peele’s recent film Get Out, I feel like I’m always catching glimpses of the natural evolution of satiric practices that were first fully fleshed out in the early eighteenth century: pointed forms of extended parody, spot-on impersonation, mock-compliment and verbal irony.

What helped fuel the rise of visual satire in the latter half of the century?

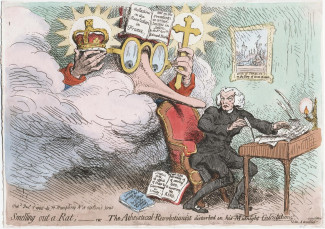

One major factor in the rise of visual satire, then, was aesthetic - that is, how artists began to visualize satiric victims and objects. But, as I also try to demonstrate in the essay, the law was also a major factor on the simultaneous diminishment of written satire and the massive growth of visual satire in the later eighteenth century, and a factor many scholars have missed. In short, during the first half of the century the courts were eager to mitigate the verbal ambiguity of written satire, the aspect of politically charged satiric works that gave both prosecutors and juries such difficulties. However, the rulings from this period, against common satiric tools like verbal irony and allegory, had little effect on later-eighteenth-century visual satires, which contained few words and tended to operate instead by repetition, juxtaposition, and intimation. My argument, then, is that satire began a period of migration, from written to visual works, and underwent a process that I call “deverbalization”: caricaturists often made at most punning and increasingly sparing use of words as the century progressed. As a result, the most libellous aspects of such satires were visual and often irreducible, legally speaking, to unambiguously prosecutable language. In short, the legal protocols of the first half of the century, which had focused intensely on mitigating the verbal ambiguity that came to typify written satire, later proved useless at policing largely deverbalized visual works.

How important is it to link examination of so many aspects of life (literature, art, law) in the 18th century in this essay?

In a lot of my research, one aspect of culture is rarely enough, in my view, ever to explain any given phenomenon. To explain a work of eighteenth-century satire, for instance, often requires knowing quite a bit about the worlds that helped to produce this odd form of literary discourse: things like rhetoric, emergent forms of literary theory and aspects of art history, of course, but also an awareness of libel laws, shifting political regimes of press regulation, the publishing industry, and the sociology of attacking a private or public individual in print. As a literary scholar, I think such interdisciplinary approaches are necessary to gain a clearer picture of how different literary genres and forms worked. My hope is that an awareness of the historical conditions that surrounded the production of a given literary text help to explain the text itself: the author’s approach, its means of publication, and how the text itself departs from and maintains certain conventions and why.

How critical was the support of the editorial team in allowing you to use so many images?