Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

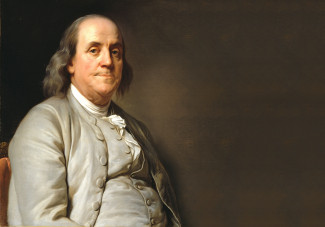

In the Shadow of Franklin

No figure has hovered over eighteenth-century printing in America or the historians who write about it more than Benjamin Franklin. The most famous colonial American printer, Franklin was by far the most successful practitioner of the trade before the American Revolution. He not only made his Philadelphia office into a venture profitable enough that he could retire at the age of forty-two, he also developed a network of satellite offices he established with printing partners all along the Atlantic coast of North America. Franklin, therefore, looms large in discussions about colonial and Revolutionary printing. As I learned while working on my book Revolutionary Networks: The Business and Politics of Printing the News, 1763-1789, that creates a problem of perspective.

Franklin maintained extensive ties in the printing trade even though he himself retired in 1748, long before the imperial crisis or the Revolutionary War. The partnerships that he established in towns from Connecticut to the West Indies continued for decades, and the fact that he had partners and former apprentices scattered around the colonies meant that he provided a model for the generation of printers who came of age during the American Revolution and its aftermath. In addition, Franklin continued to work on the infrastructure that facilitated the printing business, in particular the post office. As Deputy Postmaster General for North America from 1753 to 1774, he established crucial policies that facilitated the production of newspapers and the circulation of news, creating an environment that allowed newspapers to become key organs of dissent and key venues through which American colonists learned about anti-imperial ideology and political action. All of that work generated massive amounts of correspondence, a gold mine for historians.[1]

Clearly, Franklin was a standout figure in the colonial printing trade. Yet the very fact of his prominence has long posed a problem not only for his contemporaries but also for historians. The long shadow of his epic career, his voluminous correspondence, and his important autobiography obscure that the printing trade in the eighteenth century amounted to far more than Franklin and his cohort. His correspondence with colleagues in the 1760s and 1770s in particular has long been a rich resource for scholars working on the printing trade, even though he had long since left the trade to pursue his interests in science, politics, and other areas. For a long time, in fact, many scholars used this correspondence to argue that printers were reticent to take political stands during the Revolution, that they were—as they described themselves—“meer mechanics,” simply men who pulled the press.

It turns out, however, that Franklin and his partners were not representative of printers as a group. As late as the early 1770s, Franklin still sought an American rapprochement with Britain, in no small measure because he sought imperial advancement for himself and his son, William, then the royal governor of New Jersey. His main partners and correspondents in North America, James Parker in New York and David Hall in Philadelphia, were already in their fifties in the 1760s and fearful of the new political movement sweeping the colonies. Neither was particularly interested in taking a strong public stand against British policies. In fact, they assumed they stood more to lose than gain by standing up against the British ministry’s various taxation schemes and wrote as much to Franklin, then in London as the agent for Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and several other colonies. (They also did not survive through the Revolution: Parker died in 1770 and Hall in 1772.)

One of my goals in writing Revolutionary Networks, therefore, is to expand our field of vision more broadly to printers with a wider range of political views, from the most ardent Patriots, such as Benjamin Edes and John Gill of Boston, to the most insistent Loyalists, like James Rivington of New York. When we look at the printing trade as a whole, it becomes clear that printers were not “meer mechanics,” but instead actively shaped political debate through their businesses. By reading the range of products from colonial printing offices and examining correspondence from dozens of printers, we can see the ways in which the business practices that developed as part of the printing trade during the colonial era came to serve political ends for printers during a decade of crisis followed by war.

Over the years, I’ve become a fan of Franklin, and I have the memorabilia in my office to show for it. The first draft of the introduction to Revolutionary Networks opened with a discussion of Franklin, but it’s nowhere to be found in the final product. I had to figure out for myself just how much space to give Franklin, lest he take up all of the reader’s attention. To understand the printing trade during the American Revolution, it’s been necessary to move past Franklin, to see him as part of the story but not the whole.

Joseph M. Adelman is an assistant professor of history at Framingham State University. He is the author of Revolutionary Networks: The Business and Politics of Printing the News, 1763–1789.

[1] As of this writing, the Papers of Benjamin Franklin project at Yale University has published forty-two of a planned forty-seven volumes.