Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

From Soviet Disco to Post-Soviet Oligarchy

The present massive political corruption in post-Soviet geopolitical space is rooted in cultural consumption of the Brezhnev era (1964-1982). During this period of late socialism in the USSR, millions of Soviet young people, loyal members of Komsomol, fell in love with the catchy sound of “beat music” of the Beatles and hard rock of Deep Purple. Even ten years after dissolution of the Soviet Union, the post-Soviet space was ruled by former the Soviet hard rock fans, the representatives of so-called “Deep Purple generation,” the new post-Soviet politicians, such as Dmitri Medvedev, Prime-Minister of Russia, Yulia Tymoshenko, Prime-Minister of Ukraine, and Mikheil Saakashvili, President of Georgia.

Paradoxically, the détente of the 1970s, the period of relaxation of the international tensions during the Cold War, led to the influx of Western cultural products such as popular music and feature films in the Soviet Union. As a result, Soviet ideologists, including Komsomol ideologists, tried to control Soviet consumption of those cultural products from capitalist West, using Western popular music and video in the new “socialist forms” of leisure and cultural consumption. One among many of such forms of ideological control was a creation of “Komsomol discothèques” (or disco clubs), where Soviet young people could dance to “ideologically permitted” Soviet and Western music tunes. In the 1980s a system of Komsomol run video salons was organized to control the Western video consumption by Soviet youth. Ironically, this Komsomol movement of “Soviet disco clubs and video salons” revealed the new cultural and economic practices among activists of this movement, which became the profitable business for its organizers. The contemporaries called these organizers “the disco mafia” in the industrial cities of eastern Ukraine. Many leaders of post-Soviet Ukraine, such as Petro Poroshenko, President of Ukraine, and Yulia Tymoshenko, began their business activities by playing Western music and videos and organizing the successful “video salons” in Kyiv and Dniepropetrovsk.

By the end of perestroika in 1991, more than 100 Komsomol businesses had emerged in industrial provincial cities of Eastern Ukraine. Only few the most successful enterprises survived the brutal, post-Soviet competition during the 1990s, and created “new business corporations” such as Yulia Tymoshenko’s “Gas Empire,” Igor Kolomoiskyi’s and Serhiy Tihipko’s Privatbank, Aleksandr Balashov’s “Trade Corporation” and Rinat Akhmetov’s Liuks. The overwhelming majority of these post-Soviet successful businesses (nine from ten) were organized by or directly connected to the disco mafia – a network of rock music enthusiasts, black marketers, Komsomol ideologists, entertainers, and representatives of the Soviet tourist agencies. In this way consumption of Western cultural products like music and video during the late 1970s and early 1980s contributed to capitalist entrepreneurship in post-Soviet Ukraine.

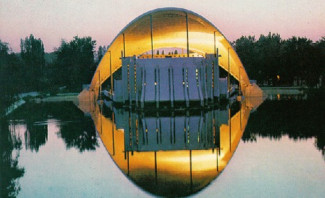

In my book Rock and Roll in the Rocket City: The West, Identity, and Ideology in Soviet Dniepropetrovsk, 1960–1985, using a story of Dniepropetrovsk, one industrial city in Soviet Union, the city, which became not only a center of the Soviet rocket industry, but also a training ground for Soviet politicians, such as Leonid Brezhnev, I explore the historical and cultural roots of the post-Soviet political and business elites that rule post-Soviet space today.

Sergei I. Zhuk is a professor of history at Ball State University. He is the author of Russia’s Lost Reformation: Peasants, Millennialism, and Radical Sects in Southern Russia and Ukraine, 1830–1917. He was a Kennan Institute Research Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in 2002–2003. His book, Rock and Roll in the Rocket City: The West, Identity, and Ideology in Soviet Dniepropetrovsk, 1960—1985, is newly released in paperback.