Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

In the Spirit of the Age

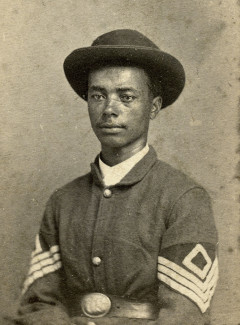

Octavius McFarland was one of the millions of nameless, faceless slaves who toiled in Southern fields during antebellum times. His ceaseless labors made life comfortable for his white masters and fueled the booming Southern agrarian economy.

His legal status, and that of other men and women of color, was at the center of a debate that sharply divided abolitionists and slaveholding elites. The secession of Southern states beginning in 1860 initiated a war of shocking violence that escalated into a long, bloody struggle.

Two years into the Civil War, on Jan. 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation that recast the war as a moral imperative to end slavery.

The Emancipation Proclamation opened the door to freedom for those held in bondage. And with came an opportunity for black men to fight in the Union army. 200,000 courageous souls joined with no permanent guarantee of freedom and no real path to citizenship.

Octavius numbered among those who enlisted during the months following emancipation. As a result, we know what he looked like, and the records of his military service tell us something about him.

We know that he became a first sergeant in the 62nd U.S. Colored Infantry, a regiment composed of about 1,000 mostly illiterate Missouri slaves, and officered by white men. The senior officers of the 62nd were a progressive lot who believed that full rights of citizenship would be granted to freedmen. Moreover, they understood that when it did, Octavius and his comrades must be prepared. David Branson, the lieutenant colonel of the 62nd, wrote in the summer of 1864, “All soldiers of this command who have by any means learned to read or write, will aid and assist to the extent of their ability their fellow soldiers to learn these invaluable arts, without which no man is properly fitted to perform the duties of a free citizen.”

Between drills and duty, the men learned the basic tools of good citizenship. Reading and writing contests were held, and prizes awarded. Octavius won a gold pen in one of the competitions.

The future looked bright.

Meanwhile, some officers in the 62nd treated the black men as if they were still slaves, administering physical punishment that was out of step with reality.

Lt. Col. Branson explained that he had “learned with regret that several officers of this command have been in the habit of abusing men under their command by striking them with their fists or swords, & by kicking them when guilty of very slight offenses. This is as unmanly and unofficer like as it is unnecessary. An officer is not fit to command who cannot control his temper sufficiently to avoid the habitual application of blows to enforce obedience. Men will not obey as promptly an order who adopts the customs of the slave driver to maintain authority as they will him who punishes by a system consistent with the character and enormity of offenses and the spirit of the age.”

Branson added, “While censuring the officers referred to, their commander makes allowance for the fact that, generally, the men who have received such punishment have been of the meanest type of soldiers; lazy, dirty & inefficient and provoking to any high spirited officer. But he is satisfied never-the-less that such treatment will not produce reform in them, while it has an injurious effect on all good men, from its resemblance to their former treatment while slaves.”

There is no evidence that Octavius suffered harsh treatment.

It seems impossible that both impulses—one humanitarian and another barbaric—coexisted in the same regiment at the same time. But they did. Yet somehow, in the spirit of the age, the officers worked through their issues and held together as a regiment.

In March 1866, the 62nd mustered out of service. Almost every soldier that has served in its ranks learned the alphabet and could read and write. Moreover, the officers and men had donated money to fund the establishment of a school in Missouri. Later that year, in Jefferson City, a two-room house became the first campus of Lincoln Institute. The fledgling school flourished and later became known as Lincoln University.

One of its founding officers, 1st Lt. Richard Foster, proclaimed, “Lincoln Institute is the child of the 62nd regiment U.S. Colored Infantry.”

And what of Octavius? He settled in St. Louis and found work on steamboats plying the Mississippi River. He died of tuberculosis in 1894 at about age 48. His body lay unclaimed in St. Louis City Hospital until local authorities buried his remains in Pottersfield Cemetery, a final resting place for those with no known next of kin. There is no evidence that he married or had a family.

Ronald S. Coddington is an editor at The Chronicle of Higher Education and the editor and publisher of Military Images magazine. He is the author of Faces of the Confederacy, Faces of the Civil War, and African American Faces of the Civil War. His latest book, Faces of the Civil War Navies, is available now.

Photo credit: Collection of the Gettysburg National Military Park Museum.