Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Now Browsing:

The Stories We Tell

We are all story tellers. Yes, even you. You are a storyteller whether you know it or not, whether you admit it or not. Answer this: when was the last time you told someone about an event that happened to you? You had a terrible day because _____ (fill in the blank.) Your neighbor’s house burned down, was painted aqua, or _____. Your attempt at making bagels failed miserably. Your mother, father, child admitted that _____. Your cat/dog was lost, then found (or not). Your wife/husband /partner decided to call it quits and moved out, taking _____. Perhaps you described a situation that is still in progress. You can’t forget that tragic or hilarious story in the newspaper about _____, still unsolved. Or you wonder what it would be like to be that other person who ____. You have dreams or nightmares about _____. Who do you tell? Perhaps you turn to someone in the dark, give someone a call, write them a text or a handwritten letter, meet someone for lunch or drinks to “catch up.” Catch up on what? On the story of your life. We all have stories to tell, but some of us feel compelled to write them down, to give them shape, to heighten the drama, maybe steal someone else’s story, to lie a little or a lot. Or to write a story whose kernel is a secret –even from ourselves. But why write the story? Saul Bellow answered this question best when he said, “Every writer is a reader moved to emulation.” I was once with a group of writers reminiscing about why we became writers. It turns out that as children we were all readers. We’d read fairy tales, the Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys series among others, Heidi, The Black Stallion, The Secret Garden, and I had “graduated” to my uncles’ paperback westerns and the book clubs, then finally to the great books in my literature classes. (Surely Harry Potter has created entire new generations of readers.) Everyone in that group was still a reader at heart. And as readers, we had come to recognize a good story when we are living one, when we hear of one, or when our imaginations go wild. It is our apprenticeship as discerning readers that has given us the tools to begin a poem, a story, a novel and follow it to its end. Eudora Welty said, “Learning to write may be part of learning to read. For all I know, writing comes out of a superior devotion to reading.”

I began to write stories in my early twenties when I was asked to teach a fiction workshop. I did my own assignments with pleasure and never stopped. After reading one of my first stories, my husband said he didn’t want to read any more stories about an unhappy wife—which I was. So, I wrote stories from a male point of view and as far as I could get from a “wife.” My first stories were told by a drummer, a mailman, a burglar, and a divorced father. They shared my aspirations and my fears, they were all in unstable situations, but they weren’t “me.” The drummer wanted to be as successful as Buddy Rich, as I wanted to succeed as a writer; the burglar realized he needed to be “nicer to his wife.” After my divorce, I did indeed write a number of stories about divorce as an unstable situation—both serious and hilarious. And to be fair to my ex-husband, I even wrote a story from his point of view.

Meanwhile, from the beginning of telling stories, I loved deciding how to tell the story, of choosing the right words because every word matters. Every detail, every point of view, every twist of the story is delivered with language. Sometimes a final sentence might not feel right—not because of what happens, though this could be the case—but it might be a matter of pure sound. As in “my final sentence needs five more syllables.”

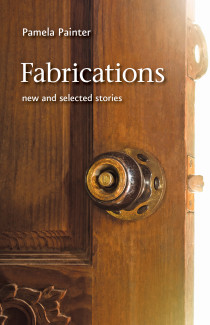

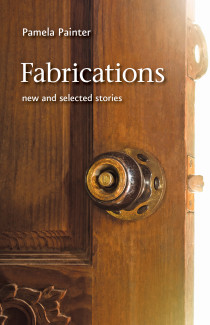

If you are reading this blog, I hope you will be tempted to read my fifth story collection, FABRICATIONS: New and Selected Stories. Choosing the stories for this book sent me back to my award-winning first collection and to welcome praise from the New York Times –“….a virtuoso performance, graceful and brave and full of feeling.” I went on to cull stories from four other collections about which Margot Livesey, one of my favorite writers, said, “These wonderful stories vividly demonstrate Painter’s wicked intelligence and ruthless humor.” Finally, I was thrilled when the General Editor of Johns Hopkins University Press, Wyatt Prunty, himself a widely-published poet, chose my “new and selected stories’” for publication. And I am honored to be a part of the Fiction Series of JHU Press.

Perhaps reading my stories will remind you of stories you have to tell. Perhaps my tales of mayhem and murder and comedy and—and life, yes life—will tempt you to begin. No matter if you only have the kernel of a story, an overheard line of dialogue, a glimmer of an unstable situation, it is a place to begin. The words “what if” (which gave the title to my co-authored textbook What If? Writing Exercises for Fiction Writers) will take you through the middle, on to the story’s end. Then a ruthless dedication to revision—I’ll save this subject for another blog—will usher your poem, or story, or novel into print.

Order Fabrications: New and Selected Stories at the following link: https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/fabrications

Pamela Painter is the author of Fabrications: New and Selected Stories, and four additional short story collections: The Long and Short of It, Wouldn't You Like to Know, Ways to Spend the Night, and Getting to Know the Weather. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Harper's, The Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, The Sewanee Review, The Threepenny Review, and elsewhere. She teaches creative writing at Emerson College.

I began to write stories in my early twenties when I was asked to teach a fiction workshop. I did my own assignments with pleasure and never stopped. After reading one of my first stories, my husband said he didn’t want to read any more stories about an unhappy wife—which I was. So, I wrote stories from a male point of view and as far as I could get from a “wife.” My first stories were told by a drummer, a mailman, a burglar, and a divorced father. They shared my aspirations and my fears, they were all in unstable situations, but they weren’t “me.” The drummer wanted to be as successful as Buddy Rich, as I wanted to succeed as a writer; the burglar realized he needed to be “nicer to his wife.” After my divorce, I did indeed write a number of stories about divorce as an unstable situation—both serious and hilarious. And to be fair to my ex-husband, I even wrote a story from his point of view.

Meanwhile, from the beginning of telling stories, I loved deciding how to tell the story, of choosing the right words because every word matters. Every detail, every point of view, every twist of the story is delivered with language. Sometimes a final sentence might not feel right—not because of what happens, though this could be the case—but it might be a matter of pure sound. As in “my final sentence needs five more syllables.”

If you are reading this blog, I hope you will be tempted to read my fifth story collection, FABRICATIONS: New and Selected Stories. Choosing the stories for this book sent me back to my award-winning first collection and to welcome praise from the New York Times –“….a virtuoso performance, graceful and brave and full of feeling.” I went on to cull stories from four other collections about which Margot Livesey, one of my favorite writers, said, “These wonderful stories vividly demonstrate Painter’s wicked intelligence and ruthless humor.” Finally, I was thrilled when the General Editor of Johns Hopkins University Press, Wyatt Prunty, himself a widely-published poet, chose my “new and selected stories’” for publication. And I am honored to be a part of the Fiction Series of JHU Press.

Perhaps reading my stories will remind you of stories you have to tell. Perhaps my tales of mayhem and murder and comedy and—and life, yes life—will tempt you to begin. No matter if you only have the kernel of a story, an overheard line of dialogue, a glimmer of an unstable situation, it is a place to begin. The words “what if” (which gave the title to my co-authored textbook What If? Writing Exercises for Fiction Writers) will take you through the middle, on to the story’s end. Then a ruthless dedication to revision—I’ll save this subject for another blog—will usher your poem, or story, or novel into print.

Order Fabrications: New and Selected Stories at the following link: https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/fabrications

Pamela Painter is the author of Fabrications: New and Selected Stories, and four additional short story collections: The Long and Short of It, Wouldn't You Like to Know, Ways to Spend the Night, and Getting to Know the Weather. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Harper's, The Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, The Sewanee Review, The Threepenny Review, and elsewhere. She teaches creative writing at Emerson College.

Login to View & Leave Comments

Login to View & Leave Comments