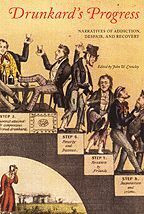

"Twelve-step" recovery programs for a wide variety of addictive behaviors have become tremendously popular in the 1990s. According to John W. Crowley, the origin of these movements—including Alcoholics Anonymous—lies in the Washingtonian Temperance Society, founded in Baltimore in the 1840s. In lectures, pamphlets, and books (most notably John B. Gough's Autobiography, published in 1845), recovering "drunkards" described their enslavement to and liberation from alcohol. Though widely circulated in their time, these influential temperance narratives have been largely forgotten.

In Drunkard's...

"Twelve-step" recovery programs for a wide variety of addictive behaviors have become tremendously popular in the 1990s. According to John W. Crowley, the origin of these movements—including Alcoholics Anonymous—lies in the Washingtonian Temperance Society, founded in Baltimore in the 1840s. In lectures, pamphlets, and books (most notably John B. Gough's Autobiography, published in 1845), recovering "drunkards" described their enslavement to and liberation from alcohol. Though widely circulated in their time, these influential temperance narratives have been largely forgotten.

In Drunkard's Progress, Crowley presents a collection of revealing excerpts from these texts along with his own introductions. The tales, including "The Experience Meeting," from T. S. Arthur's Six Nights with the Washingtonians (1842), and the autobiographical Narrative of Charles T. Woodman, A Reformed Inebriate (1843), still speak with suprising force to the miseries of drunkenness and the joys of deliverance. Contemporary readers familiar with twelve-step programs, Crowley notes, will feel a shock of recognition as they relate to the experience, strength, and hope of these old-time—but nonetheless timely—narratives of addiction, despair, and recovery.

"I arose, reached the door in safety, and, passing the entry, entered my own room and closed the door after me. To my amazement the chairs were engaged in chasing the tables round the room; to my eye the bed appeared to be stationary and neutral, and I resolved to make it my ally; I thought it would be safest to run, as by that means I should reach it sooner, but in the attempt I found myself instantly prostrate on the floor... How long I slept I know not; but when I awoke I was still on the floor, and alone... I have since been through all the heights, and depths, and labyrinths of misery; but never, no never, have I felt again the unutterable agony of that moment. I wept, I groaned, I actually tore my hair; I did every thing but the one thing that could have saved me."—from Confessions of a Female Inebriate, excerpted in Drunkard's Progress