Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Andrew Jackson as a Military Leader

This post is part of our July “Unexpected America” blog series, focused on intriguing or surprising American history research from 1776 to today. Check back with us all month to see what new scholarship our authors have to share! (Photo Credit Nicholas Raymond)

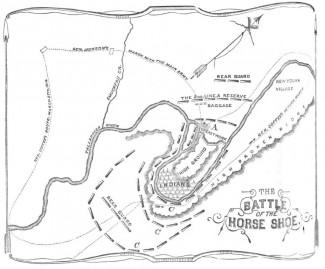

When I began work on my book on Andrew Jackson and the Battle of New Orleans, I knew he was a pretty good field commander. After all, he won the Creek War against the southern Indians and the Gulf Coast campaign against the British in the War of 1812. Jackson’s victory in the culminating battles in these campaigns—at Horseshoe Bend in present-day Alabama on March 27-28, 1814, and at New Orleans on January 8, 1815—were both decisive and one-sided.

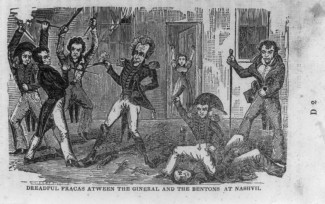

At the time I attributed Jackson’s success to two factions: his indomitable determination to overcome all obstacles and the iron discipline that he imposed on his men, which made them fear him more than the enemy. Jackson suffered from dysentery throughout the war, and he was racked by pain from a festering gunshot wound sustained in a brawl in Nashville with the Benton brothers in 1813, but these complaints never slowed him down. In addition, there were several occasions in which he lined up militia to keep volunteers from going home or volunteers to keep militia from leaving. Once he ordered his artillery to open fire on troops who threatened to go home if anyone moved. He himself was in the line of fire, and no one thought he was bluffing.

What had not occurred to me until I did my research was how successful he was in each war, winning all four battles that he personally oversaw in the Creek War and all four in the Gulf Coast campaign. As a field commander he was 8-0. His success was a byproduct of more than just resolution and discipline. Even though there is no evidence that he ever read a military treatise, he had a talent for planning and managing campaigns, and he had an intuitive grasp of strategy and tactics. He knew instinctively when to attack and when to defend, and when to withdraw and how to do so safely. He was always cool under fire and thus could issue whatever orders were needed to salvage just about any situation.

Jackson understood the importance of logistics, as did most other field commanders, but what set him apart was an unbending resolution to continue even when his supply service had failed. Indeed, on one occasion, when the governor of Tennessee recommended that he give up a campaign in the Creek War and return home, Jackson wrote an eloquent letter to butress up the governor’s courage.

Jackson also understood the importance of military intelligence. He did a particularly good job of lining up Indian allies as spies in the Creek War so that he always seemed to know where the enemy was and what he was likely to do. He sought to do the same in the Gulf Coast War, but on one occasion his intelligence service there failed him. Although he ordered a pathway to the Mississippi blocked, those charged with carrying out the mission did not act because they were convinced that the British would never find the passage. But they did, and much to everyone’s surprise, a British army showed up on December 23, 1814, eight miles south of New

Jackson’s success was also striking because of the raw materials he had to work with. He had some experienced regulars in his force, but the bulk of his men were militia, volunteers, and Indian allies, most of whom embraced rugged individualism and had a penchant for doing as they pleased—at least until they ran afoul of Andrew Jackson.

Jackson’s combat career was limited to about fourteen months, from his first battle in the Creek War to his last at New Orleans. In that period he showed such stellar leadership that he must be rated as the top field commander in the war. On both sides in the Creek War and the War of 1812, no one comes close to matching his extraordinary success.

As an amateur, Jackson represented the past. Although he remained in the U.S. Army until 1821, the postwar military establishment was increasingly dominated by professionals from West Point, who, unlike Jackson, had extensive training, eschewed politics, and deferred to their civilian masters in Washington. Although perhaps not the last of our amateur generals, Jackson certainly stands out as one of the best.

Don Hickey is a professor of history at Wayne State College in Nebraska and series editor of Johns Hopkins Books on the War of 1812. Called “the dean of 1812 scholarship” by the New Yorker, he is the author of two Hopkins books, Glorious Victory: Andrew Jackson and the Battle of New Orleans, and, with Connie D. Clark, The Rockets’ Red Glare: An Illustrated History of the War of 1812.