Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Behind the Book: Q&A With Daniel Taylor

Q: Why did you write Just and Lasting Change?

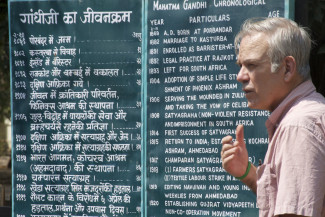

Writing any book is a challenge—especially one that seeks to give “local answers to global challenges.” The authors were lucky; we are son and father, and it happens that we began working on this many decades earlier (as the book presents as anecdotes in many of the otherwise serious scholarly chapters). The father was teaching a young son community-based health care in India, the son was teaching the father decades later how to start national parks around Mt Everest, together they were working with inspirational leaders in Afghanistan on how women could advance their own lives through using their pregnancy narratives. Across half a century of joint work, a lot of experience had grown—even more wonderful connections were made with some of the world’s most effective social change agents, and their stories are gathered in this book.

So, a huge amount of original material was accumulated from work in 70 countries and across a century of global experience. The first edition of the book that resulted was published in 2002; it sold so well that by 2016 Johns Hopkins University Press wanted a second edition. This second edition is totally rewritten. There is a lot more material from around the world because the lessons from the first edition have been used by hundreds of field workers all around the world who were applying these lessons.

Q: What was special about writing this book?

Scholarly writing is very special when done by father and son. A strong clear scholarly argument requires debate—especially when the topic is “how to improve people’s lives when they are doing the work according to their priorities.” How can outsiders, even when close observers, express the others’ priorities and experiences? This is hard writing. But when done by co-authors who span a generation and very different disciplines (international health versus community-based conservation) but who are also held by family love, the context is created that forces rigorous conclusions. More than once, our wife/mother said, “Boys, stop the arguments, and come to the dinner table so you can get something substantive inside.” Accordingly, the book is dedicated to “Mary, who taught us to accent the positive.”

Q: How does the book relate to current events in public health?

Almost every great challenge in today’s world will be solved by local answers grown from local resources but drawing on global knowledge. We live in a one world where rise global challenges of pandemics, climate change, inequity, info-insecurity, involuntary migration, the list goes on—but they all connect. There are no global answers—and there certainly is not enough money being freed up to address these with conventional solutions.

This book offers, therefore, not answers but a process. The book shares a method evolved from rigorous scholarship (method called SEED-SCALE) the gives a very doable process by anyone anywhere in the world to use what their community has, building from successes that serve as seeds in the community to grow comprehensive solutions that are sustainable. Thus, the book offers a process to address current events … wherever they may impact using resources that are already there.

Q: How did the project come together?

As I said above, as authors we were privileged to be sitting at important global discussions and living on the inside through powerful global events. Our father-son team was commissioned by then UNICEF Executive Director, Jim Grant, to lead a global task force on “how social change happens.” (Jim kindly wrote the Introduction to this book.)

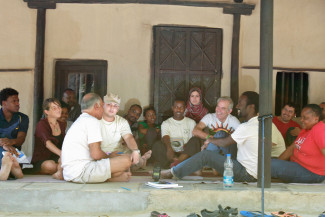

The two initial global task forces brought forward the method of:

- Build from successes (not needs)

- Work with a three-way partnership to support community growth using whatever top-down enabling frameworks exist, and stimulating outside-in innovation in that bottom-up/top-down context. (Power alone does not succeed, nor can the bottom-up alone.)

- Make decisions based on evidence (not a budget, not opinion surveys)

- Focus on behavior changes (not the usual measurable deliverables)

Using this method (which has its philosophical roots in the subfield of Complexity Theory termed Emergence), community members around the world, their government leaders also, donors who do not know how to disburse their money more effectively—all these have had extraordinary success. This book tells their stories, and it also explains how any other community members, leaders, experts, and donors can follow in these footsteps.

Daniel C. Taylor is the executive director of Future Generations, a community-based conservation and development organization, and the president of Future Generations Graduate School. The second edition of Just and Lasting Change: When Communities Own Their Own Futures is available now.