Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

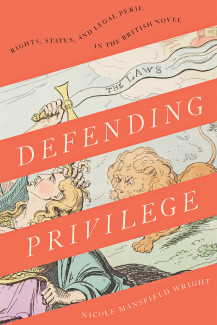

Defending Privilege – Q&A with author Nicole Mansfield Wright

Some reviewers have described Defending Privilege as an explainer of the historical roots of our current political warfare. How does your book illuminate current events?

These days, government leaders, cable hosts, journalists, and protestors are battling to decide: Who are the real victims in society—the privileged or the marginalized? The eighteenth-century literature I examine helped construct the foundations of this debate. A number of novels were penned by conservative authors aggrieved by personal experiences of what they regarded as the legal system's failure to uphold their privilege. Fiction operated as propaganda, asserting that the wealthy and those of high status ought to be given special treatment by the government and law enforcement. While the authors occasionally gave lip service to the needs of the marginalized—such as grateful slaves or industrious street urchins—these characters were used to highlight their masters’ generosity and demonstrate that the social hierarchy was righteous and the powerful deserved their high positions.

Why did you decide to write this book?

Eighteenth-century Britain was the wellspring of so many of today’s social and political institutions, from our legal system to the way we choose the leaders of our government. It was also the era of increasing visibility and empowerment for the marginalized: the poor fomented revolutions; enslaved people and their allies brought about the abolition of slavery; and the seeds of the modern feminist movements were planted. I’m interested in literature’s power to inspire readers to sympathize with characters who are very different from them.

Yet I increasingly noticed that a number of novels prodded readers to side with the privileged—including abusive aristocrats and slaveholders—as the true victims of societal injustice. Initially, I tried to reconcile or set aside the evidence that accumulated of the pervasiveness of this effort. Nevertheless, I became increasingly intrigued by this question. I recast my project to ask instead: How did this literature prime readers to feel sympathy for the privileged rather than the marginalized? This same question continues to resonate these days. On social media, for example, hundreds of people spend their leisure time defending the billionaire Elon Musk and wealthy business owners against government “shelter in place” orders designed to protect the elderly and other vulnerable populations.

What do you hope people will take away from reading your book?

I emphasize the necessity of engaging with literature and media that discomfits us—so that we can help shape its social impact. It is tempting to avoid teaching or researching this literature because we don’t want to amplify its messages or grapple with difficult, emotionally charged topics such as racism, economic inequality, populist resentment, and bias in the legal system. Yet we are depriving readers of important knowledge if we don’t tackle this material. More broadly, if scholars don’t bother to examine connections between the literature of the past and narratives spreading in popular venues that may be unfamiliar to us—including Reddit, talk radio, partisan TV channels, and fan-fiction message boards--we’re letting politically toxic messages fester unchallenged. We can’t afford to shy away from the difficult decisions involved in balancing analysis of these narratives without “giving them oxygen,” on one hand, or infringing on free speech rights, on the other. Ignorance isn’t bliss; it’s abdication of our public platform as scholars.

What were some of the most surprising things you learned while writing/researching the book?

All too often, it is assumed that “humanizing” marginalized people—that is, portraying them in literature or media as full-fledged, capable persons, rather than as stock characters or stereotypes—is the key to convincing the general public that the poor or people of color deserve civil rights. Yet in some of the literature I explored, humanization was used to support arguments for restricting rights. I was surprised to find that proslavery literature inadvertently depicted black people as complex persons who were capable of contending with whites—more so than much of the antislavery literature.

What is new about Defending Privilege that sets it apart from other books in the field?

My book defies a longstanding trend: since the 1970s, literary critics have devoted abundant attention to the ways novels give voice to the voiceless. There is a valid reason for this emphasis: previous generations of scholars too often ignored or neglected the significance of cultural contributions from—and popular representations of—women, the enslaved and people of color, the impoverished, and people with disabilities. Yet, as time wore on, literary studies has developed a blind spot: there’s a reluctance to grapple with the appeal of fictions supporting privilege beyond labeling them as harmful.

My book focuses on literary genres meant to inspire readers to sympathize not with the marginalized or the poor—the standard targets of compassion—but instead, with the wealthy and society’s elites, including those who enslave other human beings or prey on the poor.

Does your book uncover or debunk any longstanding myths?

I aim to challenge what many regard as a sacred tenet of defenders of the humanities. At a time when funding for higher education—and the humanities in particular—is under attack, it’s understandable to defend our institutions by touting the power of reading and learning to make us better people—more informed and compassionate. In addition, scholars including the historian Lynn Hunt and the cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker have done so much for the humanities, demonstrating the power of fiction to advance causes such as human rights and the abolition of transatlantic slavery. Yet what if the literature and media we consume has the potential to make us worse people—more selfish, bigoted, and prone to demonizing others?

This disturbing side of literary history is the one I bring to light. Familiarizing ourselves with historical case studies of attempts at political manipulation through literature can help generate strategies for guarding against disinformation today—just as vaccination involves using a dead form of a pathogen in order to protect against new threats.

Did you encounter any eye-opening statistics while writing your Defending Privilege?

By highlighting widening disparities in access to justice, certain historical statistics challenge one of Western society’s most cherished illusions: that with each generation, our world necessarily becomes more equitable. During the Civil Rights era, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. echoed earlier speakers in declaring: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” Unfortunately, in the decades since, his words have been twisted into a comforting myth that has lulled too many of us into political apathy and inaction: it will all turn out fine in the end, so no need to do anything to change the system now.

During the so-called “early modern period,” for example, the British court system was surprisingly accessible to poor people and women relative to what we might presume. There was even a so-called “Court of Poor Men’s Causes” that was reputed to be faster and more efficient in processing legal claims than venues for the affluent. In the later seventeenth century, however, the numbers of women and poor who accessed the courts dropped precipitously.

In my book, I reveal fascinating details regarding the causes of these changes and their impact on the marginalized. During the era I examine, poor plaintiffs dwindled, but there is a surge in poor defendants. The United States legal system is exhibiting similarly growing disparities in access to justice. Vigilance is necessary—things don’t automatically improve.

How do you envision the lasting impact of your book?

Literary study is all about interpretation and bringing to light what is not at first visible. We can move from the sidelines of culture to a lead role in helping students and the public recognize the sophisticated political techniques that are used to manipulate them. This is particularly relevant today when propaganda and disinformation are so pervasive.

I hope that my book will inspire rising scholars to expand their focus to literary works and media beyond their comfort zone and notice the connection between the past and present developments. All too often these days, well-intentioned academics in the humanities are largely “preaching to the choir” with the assumption that any reasonable person is on board with the program of social justice. One reason why liberal arts disciplines are failing to connect with the general public is because academic studies of popular culture are perceived as vilifying that culture.

Some scholars have worried that by exploring why so many people are drawn to narratives that support noxious ideologies, they will be seen as condoning or apologizing for those ideologies. Even so, we need to read the disturbing works, and we need to view the disturbing memes, in order to understand their strategies of communication and persuasion, and reverse-engineer them—not to replicate them, but to challenge them.

Order Defending Privilege: Rights, Status, and Legal Peril in the British Novel -- published on March 10, 2020 -- at the following link: https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/defending-privilege

Nicole Mansfield Wright is the author of Defending Privilege: Rights, Status, and Legal Peril in the British Novel, which was published in Spring 2020. Her work has appeared in The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Eighteenth Century: Theory and Interpretation, Eighteenth-Century Fiction, Eighteenth-Century Studies, and Toronto Quarterly. Her work has been covered by the New York Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, the BBC, NPR, and other national and international press outlets.