Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

How My New Book about Jane Austen Started with Stephenie Meyer

Guest post by Janine Barchas

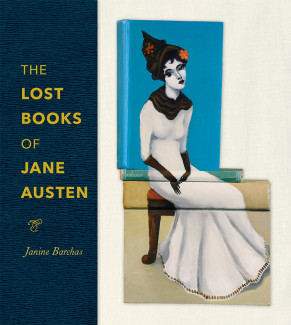

In The Lost Books of Jane Austen, I champion the cheapest and least authoritative reprints of an important author, mixing hardcore bibliography with the tactics of the Antiques Roadshow. How I came to stray from scholarly libraries to eBay and beyond, shifting from a fastidious bibliographical critic who favored “original” and “first” editions to reluctant hunter of bookish throwaways, is an odd story.

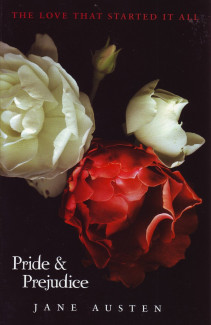

It all began in 2010 with a phone call from a distraught teacher at my daughter’s all-girls school. The teacher, now my friend, wanted to talk about teaching Pride and Prejudice for the first time to her sixth graders. Knowing her choice was ambitious, she had expected the book to challenge her savvy 11-to-12-year-olds but could not account for their response to Mr. Darcy. “Janine,” she said with a hint of despair, “all the girls seem to think his coldness towards Elizabeth suggests he’s a vampire. I just don’t know where they’re getting this idea.” After exchanging incredulities, I asked what edition the class was using. A straightforward Teen Edition from Harper Collins had been ordered by the school administrator as suitably inexpensive—one with an innocuous floral cover, reasonably large type, and no scholarly footnotes to impede the reading experience. Unfamiliar with the Twilight series, both the administrator and teacher missed the cover’s deliberate mimicry of Stephenie Meyer’s vampire romances, with their tell-tale aesthetic of red, white, and black. The students were reacting to the packaging and not the story.

After a good chuckle, we decided to turn this misapprehension into a teaching moment. I offered to visit her sixth grade armed with other Austen editions from my shelves. What a great lesson this would be for the girls about not judging books by their covers. Seeing that most of my own editions were scholarly and rather austere, I took a trip to two local used bookstores to load up on cheap reading editions with a range of cover designs. I brought my bag of books to the sixth graders, who took my expertise on Austen for granted with the same faith as they assumed my intimate familiarity with Twilight. It was a fun session. But after that bag sat around the house for another few weeks, it nagged at me. How aggressively had Austen’s early publishers turned covers into alluring marketing canvases? Had far earlier editions of Austen foreshadowed Stephenie-Meyer-style branding? Would I even recognize marketing cues embedded in a cover from long ago? First editions of Austen sold in plain boards or leather bindings, but how had cheap reprints looked to buyers in the nineteenth or early-twentieth centuries? Had cheap versions even existed, early on? Or had Austen mostly been read by the nineteenth-century elite? The standard bibliography showed no cover art and rarely described exteriors. The internet beckoned.

By browsing, I soon found versions absent from the usual inventories. At first, I collected only images, built slideshows, and gave talks about the mercurial appearances of Austen in different book formats and eras. I soon began to hanker after these marvelously lowbrow book dregs, even though my bibliographical training stopped me from granting these volumes interpretive weight or authority. After all, these were not the serious versions quoted by genuine scholars. Ergo: mine was not a serious scholarly Austen project. But thanks to academic tenure, I could indulge my curiosity. As I showed unknown books that cut against the grain of a stable and genteel Austen, my audiences grew in numbers and enthusiasm. Covers proved a popular topic, and I was invited to share some of my finds in a back-pager for the Book Review section of The New York Times.

Popularity and scholarship have always been uneasy bedfellows, however. The larger the number of unsung versions turning up on eBay and the like, the more I became aware of an uncomfortable elitism about my own stubborn professional attitude towards these reprints and their packaging. By then my shelves teemed with hundreds of cheap old Austens rarely included in the historical record and never professionally valued. What kinds of people had read them? Before I could determine the impact of these books, I needed to find out more—about original prices, publishing practices, and the history of reading.

In truth, academic libraries collect editions but people read books. Identifying and safeguarding important editions for posterity is the good work performed by academic libraries. Lending libraries, on the other hand, provide reading copies, which tend to be replaced as soon as they wear out. Scholars know this distinction and have developed a set of tools that privilege the stable holdings of academic libraries. Their resulting bibliographical inventories offer in-depth data about landmark editions, but skim over many of the derivative reprints owned by ordinary readers. When scholars talk to one another, they again cite a narrow range of important editions. This is fine for much of the critical work that scholars do, which requires anchoring references in definitive texts that are free from error. Claims about reception history and cultural engagement, however, demand a different approach.

The above is an excerpt from the Preface of The Lost Books of Jane Austen, which trials a newly democratized approach to reception history, with seldom-seen copies of scruffy survivors to surprise the most hardened Janeiac.

Order The Lost Books of Jane Austen – published on October 8, 2019 – at the following link: https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/lost-books-jane-austen

Janine Barchas is the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor of English Literature at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of The Lost Books of Jane Austen, Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity, and Graphic Design, Print Culture, and the Eighteenth-Century Novel. She is also the creator behind What Jane Saw (www.whatjanesaw.org).