Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

How "Unrepentant Nazis" became "Our Germans" - With Brian Crim

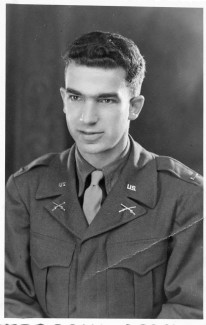

Wernher von Braun’s rocket team’s journey from captivity in Germany to their brilliant “second act” with the US Army and eventually NASA began with a series of debriefings with the Army Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC) in a ski chalet near Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Upper Bavaria. One of the interrogators assigned to the rocket team was thirty-two-year-old Second Lieutenant Walter Jessel. Jessel had explicit instructions from Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force to sort out, in Jessel’s words, “Nazi hangers-on and enforcers from technical staff in order to bring the latter to the US.” Jessel and his fellow officers faced a difficult task distinguishing between esteemed scientists responsible for revolutionary military technology and those who were either expendable or so tainted by accusations of war crimes that employing them was simply impossible. As candid as Jessel’s military screening report reads, his diary entries from that week in June are even more frank: “The team consists of rocket enthusiasts, engineering college graduates, professors, all unrepentant Nazis aware of their bargaining power with the Americans.” Jessel noted that German army personnel attached to the team understood “that their chances of going to the US are smaller than those of technicians. To improve these chances, they sing.”

Walter Jessel was no ordinary American intelligence officer. Born in Frankfurt, Germany in 1913, Jessel understood more about his interrogation subjects than their language. The product of a wealthy assimilated Jewish family, Jessel watched his native land sink into Nazi tyranny as friends and business associates either aligned themselves with the new regime or accepted it without question. Now donning an American uniform, Jessel spent the final days of the war vetting everyone from prominent Nazis to craven opportunists desperate to avoid the consequences of the previous twelve years. Jessel acquired an understanding of the culture of wartime science inside Nazi Germany, particularly the overriding ambition and amoral technocratic outlook of the rocket team living in the isolated Baltic enclave of Pennemünde. After several days of interviews and surveillance, Jessel arrived at this damning assessment of his subjects:

They were enthusiastic technicians with the mission according to Goebbels of saving Germany. As a team, they were granted all the financial support, materials and personnel they required, within the means of the German war machine. Continuance of the work depended on continued conduct of the war. At a time when the generals were dissatisfied with the party rule to the extent of attempting to overthrow it, Peenemünde was out of touch and sympathy with such developments – not for love of the party necessarily but because their work and the war were one.

While most American observers fawned over the rocket team, easily seduced by the charismatic von Braun and excited by his promises, Jessel exercised the cautious skepticism one might expect from an intelligence professional. As an educated German forced to flee his own country at the hands of men like those he interrogated, Jessel’s perspective deserved more attention than it ultimately received.

Jessel’s evaluations of his interrogation subjects were so comprehensive and insightful that historian Michael Neufeld quoted them at length in his definitive study, The Rocket and the Reich: Peenemünde and the Coming of the Ballistic Missile Era (1996). During the course of researching Our Germans I read Neufeld carefully and decided to retrieve every report Jessel wrote during his stint as an interrogator with the CIC. As a former intelligence analyst and consumer of intelligence products, both historic and contemporary, I consider Jessel’s reports unusually honest and forthright assessments obscured by thousands of repetitive and mostly indistinguishable documents. Jessel’s reports belied personality, experience, and even caustic humor. I was determined to learn more about the man behind the intelligence and soon discovered an obituary for Walter Jessel, dated April 2008. I acquired an e-mail address for his eldest son, Alfred, and requested any personal papers or memoirs which might aid my research. I was not disappointed. Not only did Jessel keep a diary from his time in the military, adding even more detail to his meticulous screening reports, he wrote a remarkable separate memoir recounting a four-month long investigation into the fate of his former classmates from Frankfurt. With the Jessel’s family’s permission, I edited and published Walter’s memoir Class of ’31 seventy-one years after he wrote it in occupied Germany, a fitting tribute to an extraordinary individual.

I decided to title my book “Our Germans” to reference Bob Hope’s famous joke uttered in the wake of the Sputnik launch on October 4, 1957. Hope took the shocking news in stride when he quipped, “All this goes to show that their Germans are better than our Germans.” While it is true hundreds of German scientists brought over by Project Paperclip eventually became our Germans, Nazi party credentials and all, I want readers to remember Walter Jessel was our German, too.

Brian Crim, is the John M. Turner Distinguished Chair in the Humanities and an associate professor of history at Lynchburg College. He is the author of Antisemitism in the German Military Community and the Jewish Response, 1914–1938 and the editor of Class of ’31: A German-Jewish Émigré’s Journey across Defeated Germany. He is also the author of Our Germans: Project Paperclip and the National Security State