Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Project Paperclip Was Stranger Than Fiction

I could not be happier with the critical reception of Our Germans: Project Paperclip and the National Security State since its release in early 2018. Reviews in the Journal of American History, American Historical Review, Intelligence and National Security, and Isis: A Journal of the History of Science Society praise the book’s integration of new research, measured analysis and argumentation, and accessible style. What struck me these past few years doing interviews and speaking to audiences about Our Germans is just how much our perception of Paperclip is shaped by its representation in popular culture. Moreover, Paperclip enjoys a prominent place among conspiracy theorists (several of whom contact me on a regular basis) who see the controversial intelligence program as either part of a secret alien agenda or the foundation of a neo-Nazi Fourth Reich hiding in the shadows. On the one hand, I certainly understand why the complex operation responsible for bringing over approximately 1,500 German and Austrian scientists, engineers, and technicians to the US for “long term exploitation” is fertile ground for popular culture. On the other hand, as I demonstrate in Our Germans, the truth about Paperclip is as compelling as anything you could find in a screenplay or spy novel.

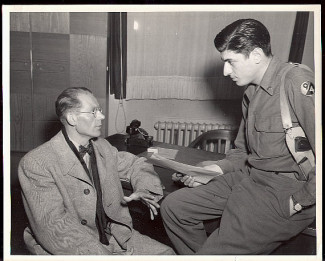

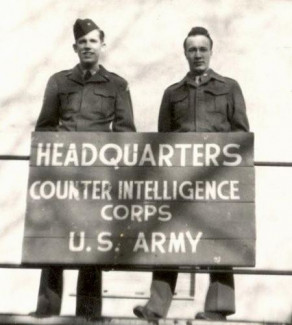

My favorite part of researching Our Germans was delving into the records of the Army’s Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC) from Fall 1945 through Spring 1946. For intelligence officers scrambling through the ruins of the Third Reich in search of “rare, chosen minds” responsible for building rockets, jet engines, electric submarines, and horrific biological and chemical weapons, the rules of engagement were like ice cream, easily melted. It was the Wild West as the CIC undermined and dodged their counterparts from the British, French, and Soviet intelligence services, all of whom were scouring the country for German expertise in a number of fields. The occupying powers agreed to one set of rules and shared responsibilities on paper, but each nation quickly discarded the fragile arrangement to acquire an elusive edge over their “frenemies” when it came to technology. Commerce Secretary Henry Wallace convinced President Truman to sign off on Paperclip because the now unemployed scientists “are the only reparations we’re likely to get.” CIC officers frantically sought to safeguard Germany’s best and brightest before they fell into the hands of a rival power, and that did not always mean the Soviet Union. I read some harrowing accounts about the scramble for German scientists in these first months after the collapse. For example, French agents snuck into the US zone and pushed scientists into moving cars and spirited them across the border into France; US and British intelligence officers, supposedly the closest of partners, came to blows over “who gets what” when it came to the vaunted Wernher von Braun rocket team; and Soviet NKVD agents used a beautiful German-Jewish refugee to lure one scientist into a hotel room where the agents “encouraged” the confused German to work for the Motherland. A sense of lawlessness and paranoia took hold of the occupation forces facing an uncertain future in what amounted to a power vacuum in the heart of Europe. The Cold War for German scientists was just one aspect of the broader Cold War emerging from the ashes of the Third Reich. Our Germans is a reminder that the history of this dynamic period can be stranger (and more entertaining) than fiction.

Order Our Germans: Project Paperclip and the National Security State – published in paperback on February 18, 2020 – at the following link: https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/our-germans

Brian E. Crim is a professor of history at the University of Lynchburg. He is the author of Our Germans: Project Paperclip and the National Security State, Antisemitism in the German Military Community and the Jewish Response, 1914–1938 and the editor of Class of ’31: A German-Jewish Émigré’s Journey across Defeated Germany. His most recent book is Planet Auschwitz: Holocaust Representation in Science Fiction and Horror Film and Television.