Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Hurricane Season Playlist

It’s June, and hurricane season has begun in the Atlantic region. Drawing on the discography of my recent book, Cultivation and Catastrophe: The Lyric Ecology of Modern Black Poetry, this blog post offers a disaster playlist to get you through these stormy months. (You can also listen to the entire Hurricane Season Playlist here: Hurricane Music)

Hurricane Katrina revealed the powerful connection between racial and environmental injustice and revealed, too, the potential for art to respond to that destructive intersection. This potential has a long history in black literature. From Zora Neale Hurston’s fictional narrative of the 1928 Florida hurricane to Shelton “Shakespear” Alexander’s poetry recitation before the gates of St. Vincent De Pau Cemetery in Spike Lee’s When the Levees Broke (2006), black writers have responded to environmental experience and ecological change, and to the experiences of historical rupture (catastrophe) and cultural continuity (cultivation) that are part of living in the natural world.

While researching the book I uncovered a parallel archive of black diasporic music that responds to environmental disaster, the recordings and transcriptions of which constitute both a history of environmental catastrophe in the U.S. and the Caribbean and a diverse, partial, and an account of black survival in the face of disaster. In Cultivation and Catastrophe, I read and listen to these sounds, both on their own terms and as shaping influences on literature. I share some of them below.

Songs of the 1928 Florida Hurricane and 1929 Bahamas Hurricane

Toward the end of Zora Neale Hurston’s 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God, a massive hurricane, usually thought to be based upon the 1928 Florida Hurricane, devastated the community of Floridian and Bahamian Migrant Workers “picking beans” in the Everglades. In Hurston’s novel, human behavior often reflects and amplifies environmental experience: the historical hurricane of 1928 was one of the most-deadly Atlantic hurricanes in history, and racist violence exacerbated natural destruction, with black workers forced at gunpoint into labor, and the Jim Crow burials that famously took place after the storm. Hurston’s novel refers to this racialization of environmental catastrophe when Tea Cake, the husband of the novel’s protagonist Janie, is instructed to bury the black dead in mass graves and the white dead in coffins; the racist social order persists even after death.

What has been less often noted about Hurston’s description of the hurricane is that it has a sound—that is, the novel invites us to hear the hurricane both as part of our sensory experience of the environment and as a form of human music. In Their Eyes Were Watching God, the hurricane bears down on the novel’s main character Janie and her circle of friends during a night of singing, dancing and playing. Hurston writes:

“Everything in the world had a strong rattle, sharp and short like Stew Beef [a musician] vibrating the drum head near the edge with his fingers. By morning Gabriel [another musician] was playing the deep tones in the center of the drum. So when Janie looked out of her door she saw the drifting mists gathered in the west—that cloud filed of the sky—to arm themselves with thunders and march forth against the world. Louder and higher and lower and wider the sound and motion spread, mounting, sinking, darking” (Their Eyes Were Watching God, 184-185).

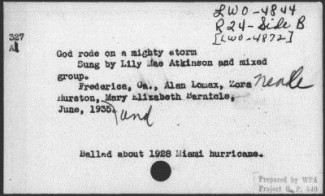

It is not surprising that Hurston is so attentive to the musical qualities of the hurricane. She was an ethnographer who traveled throughout the South and especially her home state of Florida recording black diasporic culture, and she took special interest in the opportunity to record, preserve, and transcribe the rich musical cultures that were her own as well as those she discovered in her travels. In fact, Hurston recorded one folk song about the Florida Hurricane itself, “God Rode on a Mighty Storm,” performed by Lily Mae Atkinson in Georgia in 1935. She also lived through a hurricane in 1929 in the Bahamas, which was the subject of a very similar folk tune that eventually became popular in the United States folk music scene.

George Washington and unidentified group of Negro convicts. In That Storm. Gainseville, Florida, 1936. AFS 715 A & B. American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

Viola Jenkins. The West Palm Beach Storm. Gainseville, Florida, 1937. AFS 977 A. American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington DC.

John Roberts. Pytoria (Run, Come See Jerusalem). 1959. Vol. Music of the Bahamas, Anthems, Work Songs and Ballads. Smithsonian Folkways, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Other Versions of “Run, Come See Jerusalem”: “Blind Blake” Higgs, Odetta (1958), The Weavers (1960)

- Bonus Track: Hurston also recorded many of her field recordings in her own voice on recording equipment at the Library of Congress. While these aren’t storm songs, they’re worth a listen! Evalina is one I describe in the book.

Songs and Poems of the 1927 Mississippi Floods

Just a year before the Florida hurricane, the Mississippi delta had been inundated with floods from the Mississippi and its tributaries. The results were devastating, and disproportionally affected black sharecroppers, thousands of whom were killed and many others conscripted into labor in refugee camps. It was one of the environmental factors in the Great Migration of black Americans to Northern cities, as marked in Panel #8 of Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series, which you’ll find on the cover of my book:

Although The Crisis magazine (the magazine of the NAACP) described the camps as silent, with “no sound of mourning, no lamentation,” (“The Flood, The Red Cross, and the National Guard,” 5) there was an outpouring of music that evoked the landscape of the floods and shaped the modern blues. Just as singers and songwriters like Bessie Smith strove to approximate the ecology of disaster, so too poets like Sterling Brown worked to capture both songs and storms.

Bessie Smith. Back-Water Blues. 1927. Columbia 14195-D.

Bessie Smith. Homeless Blues. 1927. Columbia 14260-D

Bessie Smith. Muddy Water (A Mississippi Moan). Written and composed by Peter DeRose, Harry Richman, and Jo Trent. 1927. Columbia 14197-D

Sterling A. Brown. Ma Rainey (1931) (audio of the poet reading)

Songs of Hurricane Gilbert

In 1988 Hurricane Gilbert traversed the entire island of Jamaica as a category 4 hurricane, causing forty-five deaths, massively damaging agriculture, livestock, schools, houses, and the tourist trade, and transforming the political landscape of Jamaica. Within a mere three weeks, Jamaican dancehall singer Lloyd Lovindeer’s funny, ironic, engaging “Wild Gilbert” hit the streets of Kingston, along with a wave of other dancehall songs, and climbed the charts to become Jamaica’s best-selling single. Since many Jamaican’s lacked electricity for months after the storm, songs played over amplified car radios became a major source of entertainment. Like Bessie Smith and Lily Mae Atkinson before him, Lovindeer sounded out the collective experiences of loss brought about by the storm.

Lloyd Lovindeer. Wild Gilbert. 1988. Kingston, Jamaica: The Sounds of Jamaica.

Banana Man. Gilbert Attack Us.

Yellowman. Starting All Over Again.

You can listen to the entire Hurricane Season Playlist here: Hurricane Music

Sonya Posmentier is an assistant professor of English at New York University. Her book, Cultivation and Catastrophe: The Lyric Ecology of Modern Black Literature, is available now.