Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Letting Go of Results: The Education of William James and My Own Medical Crisis

Life is a soul school, and some classes are harder than others.

For decades after his death in 1910, William James served as the genial uncle figure of American philosophy. He was famous as a popularizer, even though his tendencies to offer insights connecting disparate parts of life and contrasting outlooks reinforced his reputation for lack of rigor. Recently, research on the relations of dual contrasts between religion and science, mind and body, and philosophical thinking and lived experience has increased appreciation for James’s ways of thinking. My book, Young William James Thinking, tells the story of James’s evolution toward his mediating postures, and writing the book brought home to me the significance of connecting theory and life.

In December 2003, I was working on chapter 2, “Between Scientific and Sectarian Medicine.” However, in previous weeks, blurry vision in my left eye was making reading increasingly difficult. My eye doctor conducted some tests, including an MRI, “just to rule some things out.” A few days later, the doctor called to say that the MRI results explained my blurry vision: I had a brain tumor growing on my pituitary gland and pushing on my optic nerve. This craniopharyngioma tumor is extremely rare, and sadly, it usually strikes in childhood. Within a few hours, after immediately imagining the worst, and getting advice on next steps, I was back at my writing desk, revising the paragraph I had written the day before.

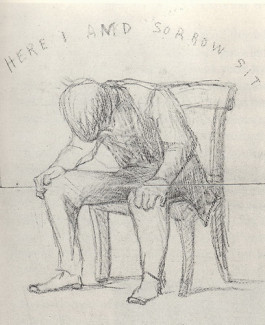

Despite my personal woes, I immersed myself in the words of William James, about his education in a range of diverse nineteenth-century medical practices. In my writing, I was developing a picture of his troubled life in the late 1860s. He felt constrained by his father’s spiritual philosophy which he found difficult to square with his scientific education. He was completing his medical degree in 1869, but his physiological learning showed little connection to his philosophical interests and offered few vocational prospects. Authoritative science suggested that his own willful efforts would be for naught in the face of material factors determining life’s directions. He suffered eye and back problems and bouts of depression that prompted thoughts of suicide. And he even doubted his long-term sanity, while growing so awkward with women that he vowed never to marry. The prospects for his career and personal life brought him to a slough of discouragement, and yet the very crucible of his own troubles also suggested insights about a more hopeful path.

In his young adulthood, James shifted his attention to the current tangible facts right in front of him. He stopped focusing on his long-term goals for finding work in psychology or philosophy because that was so out of reach. Instead, he paid attention to the immediate present, unhooked from past facts or future dreams. He looked carefully at his current work, the study of human physiology with reflections on the philosophical implications of his science. While scrutinizing that particular work and finding it a worthy task, he resolved to stop worrying about what it might lead to. He declared, “Results shd. not be too voluntarily aimed at or too busily thought of.” Instead, just work in the present without dwelling on how you arrived at this point and without expectations about future achievements. Do the job that feels right at this moment, and let the future emerge, with all its uncertainties, from this good work.

When I heard my MRI results, like James, I too was discouraged, but also as with him, letting go of results had a “potent effect in my inner life.” Without knowing my medical fate, I continued my “small daily pegging,” as James described the tedium of regular work toward a goal that at any one moment appears well out of reach. My own daily pegging, with attention to careful and thorough coverage, led to expectations for recognition of all that hard work—prospects now dashed by that growing mass of flesh in my head. I could not plan for publication, and I might not even complete the book, but I was left with the process, the doing, and that was what mattered at that moment of medical crisis. I had read James’s words about the challenges he endured, his utter discouragement, even as he continued learning and working. But now I had “knowledge by acquaintance,” as James would say about realizations that surge from lived experience, about the firm resolve he forged in his youth to continue his efforts. Minor achievements of each day became his goals in and of themselves without any idea of whether they would lead to anything.

From 1860 to 1877, from his first time studying outside his home through his years as a teacher of science, James searched for direction in his vocation, philosophical orientation, and personal life. He never fully solved the problems of his youth, but he worked through them and despite them, without expecting results. This proved to be a freeing mental posture that enabled him to make his “first act of free will” in 1870, asserting that his own choices could have substantial impact. From this posture, he grew comfortable living “life without guarantee” and constructed theories that transformed his earlier uncertainties into assets.

The uncertainties of James’s early life left him ambivalent and hesitant. However, when he learned not to expect results, the prior pain of ambivalence about different sides of issues and different choices became a window for looking at multiple sides of things without blinking out any of the parts. He embraced a decisive ambivalence. He developed his pluralist philosophies, with openness to different assumptions and diverse points of view. He attended to the simultaneous mental and physical elements of psychological life. His pragmatism incorporated the perspectives of rationalism and empiricism. His radical empiricism showed the relation of subjective and objective perspectives. And in his religious studies, he evaluated the subliminal psychology of spiritual experiences. In his earlier posture, he was torn over these contrasts, precisely because he expected results—he expected one side to become the exclusive answer. However, not expecting results enabled a more comprehensive view and served as the basis for innovative thinking.

Problems as opportunities? That’s not how they feel. When in the thick of problems, they are just problems. Indecision, depression, lack of direction, and health issues are all incredibly discouraging. James’s insight builds toward the long-term precisely by not thinking about it. Every problem calls for immediate action, with plans to address that immediacy. At first, my audacious tumor visitor wore the garb of a foul villain, invading my space and threatening murder. But it later became a difficult but welcome guest, a stern guide and rigorous teacher.

I lived out the old saying that “life is a soul school,” and I experienced that some classes are harder than others. My tumor was most certainly a problem, and as with James, I explored both alternative and mainstream medical remedies; and like him, I practiced “curapathy,” trying the least invasive practices first. When homeopaths and acupuncturists could not gain traction, maintaining that their remedies would have been preventive at earlier stages, I turned to scientific medicine and scheduled surgery for removal of most of the tumor and radiation of the remnant to reduce the chances of recurrence.

Scary stuff, with no certainty of result. I could have gone blind, lost some mental function, or worse. I pictured the Grim Reaper saying, “Are you ready?” while I petitioned for postponement through the good work of the surgeon and radiologists. Thankfully, the extension was granted, and more. I developed an attitude of gratitude for this lease on life, for full use of my brain, and for the return of my vision. From these, much follows, starting with an approach to life goals without expecting results. This posture prods toward achievement, without clinging to an uncontrolled and unpredictable future. James made that move as a young adult, growing comfortable with contingency, and that stance opened him to his most creative theorizing. Similarly, my medical adventure prodded me to write this book, in my own way, with attention to thoroughness, and without expecting results.

Paul J. Croce is a professor of history and American studies at Stetson University and a former president of the William James Society. He is the author of Science and Religion in the Era of William James: Eclipse of Certainty, 1820–1880. His latest book is Young William James Thinking.