Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

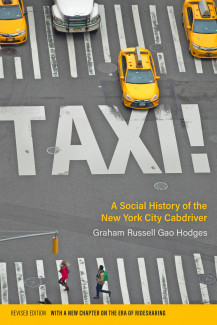

Taxi: A Social History of the New York City Cabdriver

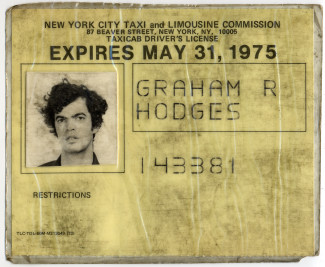

I drove a taxi in New York City from 1971-1975, graduating from hacking as a part-time earning a 42% commission on each fare to becoming a “steady man” who earned 49% of each day’s receipts plus tips. My first hack was a broken-down Dodge Polara with a smoky interior, bad breaks, a clunky transmission, and very weak shock absorbers. When I ascended to full-time status in 1973 Dalk Service, my garage, awarded me a brand-new Polara, which I drove until I totaled the car in a late-night accident. Dalk Service promptly fired me. I then worked for Frenat Taxi Company for two years until the dispatcher, irritated at my surly, defiant attitude, fired me, ending my career as a cabdriver. Unlike unfortunate drivers of today, I always earned money each day. But after five years behind the wheel, my body ached after each shift.

I mention these conditions because they are part of the background story of any cabdriver of that period, qualities that I tried to capture in my book, Taxi: A Social History of the New York City Cabdriver. As I explained in the 2008 first edition of the book, published by Johns Hopkins University Press, cab drivers were “encyclopedias of the city,” everymen who personified the tough, wisecracking New York City working men. Cabdrivers were also vulnerable, self-loathing, chronically unable to organize unions to advance collective rights and always ripe for bullying and exploitation by rapacious fleet owners and dispatchers. Conditions have become much worse since then.

Dalk Service was a fleet of several hundred cars. Daily, I joined other drivers “shaping up” as we waited for available. Generally, it was first come, first serve, but the dispatcher was known to play favorites. There was no sense of community among the disparate drivers who waited several hours just to climb into a dilapidated cab.

Owner drivers were different. They owned a medallion worth about $25,000 at the time, rising to over $200,000 by the early 2000s. Owner-drivers bought and maintained their own cars, often ornamenting them lavishly. They had their own association, the League of Mutual Taxi Owners (LOMT) and carried themselves haughtily around fleet drivers like me.

Owner drivers and fleet owners benefitted enormously in 1979 when the Taxi & Limousine Commission (TLC) switched driver compensation from commission to independent contractor. Owner-drivers now could lease out their cars and medallion and live off the profits without working at all. Fleet owners no longer had to pay for gas or maintenance, and enjoyed sure earnings. As I demonstrate in the book, fleet drivers rapidly became proletarianized. By 2000, only about four percent of New York’s cabdrivers were native-born. Once a first rung on the ladder of social mobility, the job had become more dead-end than ever before. Earlier in the twentieth-century, cab drivers had been heroic or comic figures in American film and literature. Now, they were portrayed as dangerous outsiders. Think of Travis Bickle from the 1975 Martin Scorsese film, Taxi Driver. A decreasing number of owner drivers made a living while the bulk of hackmen struggled to stay afloat day-by-day.

Shortly after the first edition of my book was published, the taxi world changed. In the decade since, I have realized how much the book needed updating to remain current. The iPhone debuted in 2007 and smartphones became enormously popular within two years. In 2011, Travis Kalanick and other entrepreneurs created ride-hailing apps for the new gadgets. Initially limited to the limousine market, Uber and its competitors, Lyft, Juno, Via, and others soon invaded the taxi market. Using illegal interventions, the ride-sharers soon captured much of the business. Passengers thrilled to the luxury of pressing a button on their phones, and then following the progress of the pickup. No money was exchanged, and initially, no tips were required. A second, far less visible force was illegal market manipulation of the value of the medallion. In the aftermath of the 2008 recession, loan officers and fleet owners artificially jacked up the value of the permit, while saddling recent immigrants with exploitative lending. The TLC watched passively as drivers with little credit borrowed $800,000 and more to buy the inflated medallion. After Uber and other ride-sharing companies flooded the New York City market in 2015 with tens of thousands of drivers and cars, the medallion’s value collapsed. That led to widespread bankruptcy among drivers and multiple suicides. I wanted to tell that story, so I have added a full chapter to my book. Desiring to add more personal information, I brought in a preface detailing my years as a cabdriver.

The cabdrivers’ saga always needs new interpretation. In the weeks since publication, a powerful new assault has badly damaged the industry. COVID-19, the coronavirus, has shut down New York City and ended any cab business. How long that will last is unknown but many drivers will not be able to overcome debt and lack of income. My recommendation, once the current plague has passed, is to make medallions, now hoarded by brokerages, available for lower prices to drivers, thereby resuscitating the true value of the permit and giving hope to a new generation of drivers.

Order the revised edition of Taxi: A Social History of the New York City Cabdriver – published on March 17, 2020 – at the following link: https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/title/taxi

Graham Russell Gao Hodges, who drove a New York City cab for five years in the 1970s, is the George Dorland Langdon Jr. Professor of History and Africana Studies at Colgate University. He is the author or editor of seventeen books, including Taxi: A Social History of the New York City Cabdriver, Black New Jersey: 1664 to the Present Day, and Anna May Wong: From Laundryman's Daughter to Hollywood Legend.