Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Scalps: Charged Revolutionary Rumor

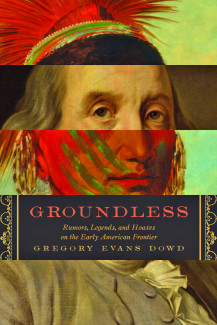

The following is an excerpt from chapter eight of Gregory Dowd's latest book, Groundless: Rumors, Legends, and Hoaxes on the Early American Frontier. Check back with us every Thursday in the month of November for more Groundless excerpts highlighting word-of-mouth tales from Early America.

The rumor first rose along the road between Lexington and Concord. The guns that had fired at Concord’s north bridge now fired to the east, and the battle still grew. Having accomplished much of their objective, several companies of British light infantry hustled in a disciplined retreat toward Boston; panic had not yet set in. They met, along the way, the dying man. From his badly mangled head the rumor multiplied and took flight: the suddenly savage country people scalped the king’s soldiers; they scalped the wounded along with the dead; they had already brutally tortured a fallen grenadier. Airborne, spiraling, noisy, and shape- shifting, the flock of rumor commanded the attention of British and insurgent leaders.

British officers quickly printed a version for distribution. They testified before imperial officials. One of the first to speak, Lieutenant William Sutherland, said that while fighting at Concord, he had taken a bullet, “a little above my right breast which turned me half around.” He had left two comrades “dead on the Spot, one of which I am told they afterwards Scalped.” I am told: it is the language of rumor. Lord Percy, who did not fight at Concord but who had reinforced the retreating Regulars as they regrouped at Lexington, picked up the tale. He deplored the “cruelty and barbarity of the rebels, who scalped & cut off the ears of some of the wounded men who fell into their hands.” Years later, as the war drew to an end, a British ensign recalled that the story had excited the 10th regiment. If we can trust his memory, the news had grown by the time it spread to his company: four troops had been “Killd who was afterwards scalp’d their Eyes goug’d their Noses and Ears cut of, such barbarity exercis’d upon the Corps could scarcely be paralleld by the most uncivilized Savages.”

General Thomas Gage, the imperial governor of Massachusetts, rushed into print his own version of the disastrous events at Lexington and Concord, including the story that several British companies returning from the north bridge had “observed three Soldiers on the Ground one of them scalped, his Head much mangled, and his Ears cut off, tho’ not quite dead; a Sight which struck the Soldiers with Horror.” Here Gage scaled back the numbers scalped from “some” or “four” to only “one,” but he left the act of scalping—alive—intact. In our own time, historian David Hackett Fischer says of the scalping and its news that “It instantly changed the tone of the engagement ... The thin veneer of 18th century civility was shattered by this one atrocity at the North Bridge.” Rumor smashed civility, became legend, and lives.

Actual eyewitnesses said nothing of scalping, at least not exactly. Five British soldiers later testified under oath that they “saw a Man belonging to the Light Company of the 4th Regiment with the Skin over His Eyes Cut and also the Top part of His Ears cut off.” This describes mangling of some kind, but it does not fairly describe a scalping. Still, the story has drawn the attention of historians loath to ignore the charge that simple New England farmers in this most heroic moment of their history had scalped a Regular at famed Concord. Long ago, after carefully examining the evidence, historian Allen French reached a reasonable judgment: he held the minutemen not guilty, at least not beyond doubt.

That said, someone murderously mangled the soldier, who, in the casual disregard of eighteenth- century armies for common men, remains nameless. Local Concord legend concurs with the British accusation that the dying man suffered a vicious and inhumane torment. But the British charge had it, precisely, as a scalping, and the idea that good country people of John Adams’s Massachusetts had taken up such ritual American Indian forms of violence ignited a controversy that has forever obscured the victim’s actual fate. The English press charged the Americans with a “savageness unknown to Europeans,” citing as evidence the scalping and, further, the eye gouging at Lexington and Concord: “Two soldiers who lay wounded on the field, and had been scalped by the savage Provincials, were still breathing . . . Near these unfortunate men, . . . a soldier . . . appeared with his eyes torn out of their sockets, by the barbarous mode of GOAGING, a word and practice peculiar to the Americans.” The nature of American “humanity,” wrote another, “is written in indelible characters with the blood of the soldiers scalped and googed [gouged] at Lexington.”

The Provincial Congress of Massachusetts could hardly ignore the claims and it issued an official rebuttal. Without explaining what actually happened to the soldier, the insurgent government printed eyewitness testimony that denied the scalping and ear cropping. What is more, the provincials accused Gage of printing the story “in order to dishonour the Massachusetts people, and to make them appear to be savage and barbarous.” The dishonor fell, then, on a lying Gage. The insurgent press quickly joined in, attacking His Majesty’s officers as deliberate purveyors of falsehoods.

The scalping at Concord is groundless rumor become legend. True or false, the story itself remains a fact tied up with America. Suppose, counterfactually, that the Regulars had marched against a movement in, say, the village of Wolverly, England; no one would have spoken of scalping. But the actual guns were fired not in imaginary Old England but in actual New England, so imaginary hair was torn in indigenous style from a British head (or heads). That the poorly grounded story rang true to the imperiled imperial Regulars on that April day makes eighteenth- century American sense. Taken by devastating surprise at the strength of the Massachusetts insurgency, the smart soldiers and their officers began talking of Indians, of scalps, and of savagery. They spoke in echoes of the Monongahela and Fort William Henry.

Gregory Evans Dowd is a professor of history and American culture at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is the author of A Spirited Resistance: The North American Indian Struggle for Unity, 1745–1815, War under Heaven: Pontiac, the Indian Nations, and the British Empire, and, most recently, Groundless: Rumors, Legends, and Hoaxes on the Early American Frontier.