Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

The St. Bernard: Alpine Rescue Dog or Manchester Manufacture?

The much-loved St. Bernard dog we know today was created by Victorian dog fanciers. It bears little semblance to the rescue dogs said to have been kept by Swiss monks on the St. Bernard Pass in the early nineteenth century. The leading champion of the new St. Bernard, defining its form and introducing it at dog shows, was the John Cumming Macdona, the colourful vicar Cheadle, now in Greater Manchester. Not only was the dog’s physical form changed and standardized when it became a show dog, but the preoccupation of Victorian breeders with fancy features and pure blood led to inbreeding and health problems.

Photo: The St. Bernard today

Our new book, The Invention of the Modern Dog, demonstrates that all types of dog, previously kept for work, sport, or companionship, were refashioned over the Victorian era. These changes were the product of the coming of fancy dog shows, which were pioneered Britain and then copied around the world, with consequences for dogs everywhere. The Victorian dog fancy radically changed the way we see and breed dogs; from types defined principally by function to breeds defined by form. The doggy world uses the term conformation. With the functional types, variation, say in size, coat and color, was normal and enabled dogs to cope with different tasks and terrain. With conformation breeds, breeders aimed to produce uniformity to tight specifications across the population and greater differentiation between breeds.

The difference between dogs at the beginning and the end of the Victorian era can be compared to how colors appear in a rainbow and on a modern paint sample card. The former has distinct colors, but these vary in hue and shade, bleeding into one another where they meet. The latter consists of distinct, separated, and uniform blocks of color. The analogy can be stretched to the proliferation of breeds. The small number of dog varieties in the early nineteenth century can be seen as akin to the seven colors of the rainbow, while the 204 breeds now recognized by the British Kennel Club (or the 332 by listed by the Fédération Cynologique Internationale) are like the great range of color shades now produced.

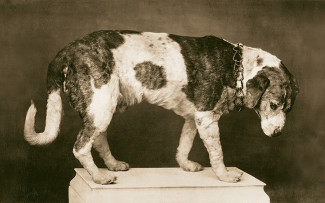

The rescue work of the dogs kept by the monks in the hospice on the St. Bernard Pass had come to prominence in the early nineteenth century through stories of the heroism of a dog called Barry. Then called Alpine Mastiffs, a painting by the popular Victorian artist Edwin Landseer of two dogs ‘reanimating a traveler’ popularized the false idea that these dogs carried a barrel of brandy on their collar. Barry supposedly saved over forty lives, and his taxidermied body was put on display in the Bern Natural History Museum, where it can still be seen today.[1] In fact, and very telling of the power of the notion of breed, the original Barry was changed in 1923. He was made taller, given a larger head, and this was raised to make him appear more noble. The modifications were made because visitors complained that the exhibit did not look like a St. Bernard! Visitor’s ideal was, no doubt, Macdona’s Manchester manufacture.

Photo: Pre-1923 Barry © Natural History Museum of Bern. http://www.nmbe.ch/en/informieren/aktuell/news/barry-exhibition-swiss-icon

Photo: Barry today - by Lisa Schäublin, Naturhistorisches Museum Bern © Natural History Museum of Bern. http://www.nmbe.ch/en/informieren/aktuell/news/barry-exhibition-swiss-icon

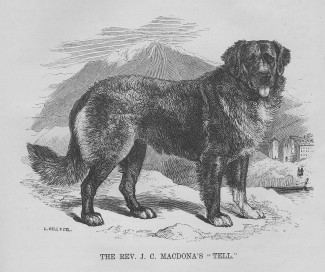

However, even the modified 1923 Barry was a very different size, coat, and color from that adopted at British dog shows. Macdona’s most famous dog ‘Tell,’ an alleged descendant of Barry, looked quite different. He was larger, darker, and had a longer, rougher coat. The influence of Macdona was evident in the first Kennel Club Stud Book, where more than half the entries had the blood of his dogs. There was a royal connection which helped popularise the breed. Macdona had been a chaplain to Queen Victoria, and the Prince of Wales owned several of this dogs. British St. Bernards were exported around the world. American dog fanciers bought their St. Bernards from England, not Switzerland. In 1888, the leading show dog of the era, Plinlimmon, was sold in 1888 to the actor J. K. Emmett for £1,000 ($5,000 then), equivalent to £105,000 ($135,000 today). Unsurprisingly, Plinlimmon’s mother had been bred by Macdona.

Photo: ‘Stonehenge’, The Dogs of the British Islands (London: Horace Cox, 1867), opp. p. 76.

St Bernards are emblematic of how dog breeds were imagined by Victorians. Macdona assumed that the physical form he preferred would cope better with snow drifts, its dark color would be easier to spot, and a shaggier coat would protect from the cold. As they were concerned with ability rather than aesthetics, the monks did not favor a particular physical form at all, rather they for stamina, courage, and character in their dogs. In fact, fanciers recognized both rough- and smooth-coated St. Bernards, and that a lighter, smooth-coated variety was most common in the Alps. However, they preferred their version on aesthetic grounds and because its newly invented conformation suited its new function: winning prizes in urban dog shows, rather than rescuing travelers in Alpine snows.

The coming of breed changed dogs internally as well as externally. The preoccupation with fixing a particular fancy feature, and with pure blood, led to inbreeding and what contemporaries called deterioration. Writing on St. Bernards in 1907, Robert Leighton, an authority on dogs, observed that breeding for shows had turned St. Bernards into ‘cripples’ because they were too tall and heavy. He called for new conformation standards. He wrote: “The St. Bernard is a purely manufactured animal, handsome in appearance certainly, but so cumbersome that he is scarcely able to raise a trot, let alone do any tracking in the snow.”

Since the Victorian era, standards for individual breeds have been remodeled many times and continue to be changed today. Breed standard has been the product of negotiation between fanciers, and each could have been different. Indeed, breed itself could have been differently conceived, say, allowing greater latitude in the specification of features. History shows that there is no reason why any breed has to have a particular look or inherited health conditions.

Michael Worboys is emeritus professor in the Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine at the University of Manchester. He is the co-author of Rabies in Britain: Dogs, Disease and Culture, 1830–2000. Along with Julie-Marie Strange and Neil Pemberton, he is the co-author of The Invention of the Modern Dog: Breed and Blood in Victorian Britain.

[1] Liv Emma Thorsen, “A Dog of Myth and Matter: Barry the Saint Bernard in Bern,” In Liv Emma Thorsen; Karen Rader & Adam Dodd(ed.), Animals on Display. The Creaturely in Museums, Zoos, and Natural History. (Penn State University Press. 2013), pp. 128 -153.