Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Testing Theories: Edison’s Scorecard

This post is part of our July “Unexpected America” blog series, focused on intriguing or surprising American history research from 1776 to today. Check back with us all month to see what new scholarship our authors have to share! (Photo Credit Nicholas Raymond)

When part of your daily routine is to sift through the papers of the world’s foremost inventor, you begin to expect the unexpected. Still, it’s hard not to be surprised when you come across designs for a steam-powered snow remover or an electric cigar lighter or at times a surrealistic poem in the unmistakable handwriting of the great man himself—Thomas A. Edison. But perhaps the most surprising and enigmatic document of all is what we at the Thomas A. Edison Papers dubbed “The Scorecard.”

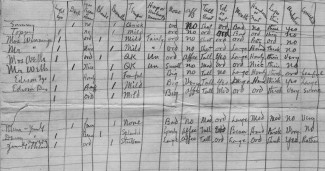

What we have since given the more dignified title “The Chart of Physiognomic Traits” and published in Volume 8 of the Papers of Thomas A. Edison first came to our attention when Tom Jeffrey, the editor of the digital edition, discovered it in a box of Edison family correspondence that had come to our office for scanning. Oddly, this undated chart did not seem to bear any relation to the other documents in the box. But it seemed important because Edison had obviously put some effort into rating the personal and physical attributes of associates, friends, and acquaintances (and of himself). Its three handwritten pages made for a dense grid of more than sixty names and fifteen traits, from hair color, “temper,” “Effectionate or not,” “Mouth,” to levels of ambition and conceit, as well as comments like “Unreasonable.” The question was: Why? What meaning did it have?

One thing, though, did stand out. Edison had used different writing implements to create the various sections of the chart. This suggested that he did not compose it at one sitting. My colleague Allie Rimer noticed that the first section, written in ink, included Edison’s business acquaintances and their wives from New York and New Jersey. The next section, written in pencil, included people he had vacationed with at Winthrop, Mass., in the summer of 1885, giving us a sense of how to date the document. Another grouping was of people Edison encountered on his trip to the Chautauqua Institute in August of that year. And then there was a whole page or more listing people who were unknown to any of the editors. These, it turned out, were almost all from Indianapolis, where Edison made a brief stop in 1885.

The Winthrop connection suggested that the “scorecard” bore some relation to Edison’s wish to remarry. He had gone to Winthrop to the summer home of friends Ezra and Lillian Gilliland to meet marriageable women Mrs. Gilliland had invited there. These included Louise Igoe of Lillian’s home town of Indianapolis and Mina Miller of Akron, Ohio. The fact that Edison used the chart to assess the beauty and temperament of a number of single women and that he also evaluated whether the marriages of his friends were happy suggest that he created the chart to analyze who might make him a good wife.

But the Winthrop connection also suggested other possibilities. During his stay, Edison had read works by the eighteenth-century physiognomist Johan Lavater and by the English psychologist Francis Galton. Lavater had written that scientific analysis of a person’s facial features could be used to determine character, something in which Edison had had an interest for quite some time. The chart might therefore be seen as an experiment testing Lavater’s assertions.

The most perplexing part, though, of Edison’s scorecard were the final entries. These didn’t conform to the idea of the chart as a courtship document or as a test of Lavater’s theories. In these entries, Edison combined the physical and psychological attributes of himself and various women he had met, which might have been related to his search for a suitable mate. But he also made composite word studies of Mina Miller, who became his second wife, and his friend Jim Gilliland, and, most perplexing yet, of Jim Gilliland and Lillian Gilliland, who were in-laws. After a good deal of discussion among the editors, our conjecture was that these studies were made in response to reading Galton, a eugenicist who believed that composite photographic portraits could be used to find common physical traits indicative of certain psychological characteristics. In short, Edison may have been testing Galton’s theories, too.

Daniel J. Weeks is an assistant editor for the eighth volume of The Papers of Thomas A. Edison: New Beginnings, January 1885—December 1887, which is available now.