Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Weapons of Democracy: 4-Minute Men

This post is part of our July “Unexpected America” blog series, focused on intriguing or surprising American history research from 1776 to today. Check back with us all month to see what new scholarship our authors have to share! (Photo Credit Nicholas Raymond)

As we rapidly approach the centenary of the US entrance into World War One (April 1917), it’s worthwhile to revisit one of the most enduring legacies of our wartime participation that continues to have profound political consequences a century later: the management and shaping of public opinion at home and abroad, thanks to the creation of the largest and most effective deployment of propaganda the world had ever experienced. One week after the US declared war on Germany and Austria-Hungary, President Woodrow Wilson established The Committee on Public Information (CPI) under the direction of Progressive muckraker George Creel.

As a journalist experienced in advocacy, Creel shrewdly grasped how values and beliefs in favor of the war and Wilsonian democracy could just as easily be manufactured for citizens as by them via the mechanisms and rhetoric of mass publicity. A combination of teacher, preacher, patriot, and bombastic huckster, Creel immodestly titled his own account of the agency How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Information That Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the Globe.

Decried by philosopher John Dewey as a “conscription of thought,” CPI propaganda saturated Americans and nations abroad from April 1917 to the end of the war in November 1918 with a barrage of leaflets, pamphlets, news bulletins, schoolroom materials, films, and Liberty Bond campaigns, in every available medium, including “the printed word, the spoken word, the motion picture, the telegraph, the cable, the wireless, the poster, the sign-board,” to quote Creel.

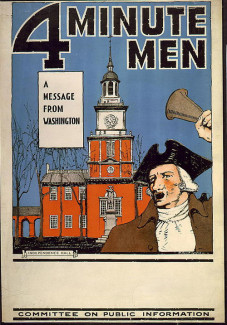

The CPI’s most innovative program, little known today, but astonishing in its scope and impact on American society during the war, was The Four Minute Men program (4MM). This was no ordinary speaker’s bureau. Two or three times a week,

By the end of the war, Creel estimated (conservatively) that at a cost of a paltry $100,000, a total of 75,000 volunteers had delivered over 755,000 speeches to a recorded aggregate of 314,454,514 American men, women, and children—more than three times the nation’s entire population! Unlike political rallies that tended to preach to the converted, the 4MM targeted a cross section of Americans from all walks of life (everybody loved movies). In this way, the 4MM in effect served as a national broadcast system before the commercial advent of radio that was actually more effective than disembodied wireless because it enabled face-to-face communication on a massive scale. After the war there were calls to continue the program as a community-based model for civic participation, but nothing came of these proposals. And yet during the eighteen months the US was at war, the 4MM managed to negotiate a whole series of tensions at the heart of American democracy, between the federal and the local, between traditional oratory and modern modes of mass persuasion, between voice and print, between control and freedom, between conformity and originality, between the organic and the mechanical, between ethnic/racial identity and national identity. It remains a unique episode in ongoing efforts by the state, by corporations, and by individuals to direct and control what citizens think, believe, and feel.

Jonathan Auerbach is a professor of English at the University of Maryland–College Park. He is the coeditor of The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies, and his book Weapons of Democracy: Propaganda, Progressivism, and American Public Opinion, is available now.