Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

When the National Pastime Wasn’t National

Racial tension is alive and well in America. Think Ferguson, Missouri; politicians vying for the African American vote; disputes over statues of Confederate soldiers and the Confederate flag; the Supreme Court’s rejection of two newly-drawn electoral districts in North Carolina because the legislature relied too heavily on race; Freddy Gray’s death in the custody of six Baltimore police officers and the rioting that followed; racial slurs directed at Baltimore Orioles’ center fielder Adam Jones by a Boston Red Sox fan in 2017.

Racial issues have been with organized baseball since its inception shortly after the Civil War. My introduction to them came in the spring of 1948 at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. I was seven years old. The Brooklyn Dodger’s black second baseman immediately caught my eye. “Who’s the black guy?” I asked my dad. “Shhh, not so loud, son,” he said. He quietly explained to me that Jackie Robinson was the first black to play in the majors and that it was a shame there weren’t more like him.

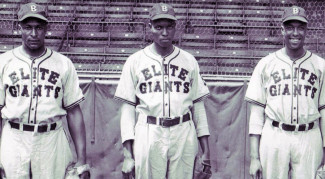

The game came back to me 60 years later as I was casting about for a book to write. Long a baseball fan, baseball seemed a natural topic. As a sociologist, the Negro leagues interested me. Baltimore, once home to several Negro League teams, was only forty miles from my home in Garrett Park, Maryland. Hence was born the idea for this book which tells the story of how race affected one of those teams, the Baltimore Elite Giants, and the city it called home from 1938 to 1951. Parallels can be found in other cities.

In addition to the Elite players and their exploits on the field, I learned many things. The most significant for me are:

- Black baseball provided a haven for African Americans, especially on Sundays. After church, fans went to Bugle Field where segregation and discrimination didn’t exist. Many brought a picnic basket. They sat anywhere they wanted with friends. Bottles were known to be passed from one to another. Bets were placed. A good time was had by all. Some also attended games at the larger, more comfortable, Oriole Park where the white International League Orioles played but did so at the cost of segregated seating and caustic remarks by whites.

- Baseball segregation was stricter in Baltimore than in other big league cities. Owners of such parks as Yankee Stadium, Shibe Park, Ebbetts Field, and Griffith Stadium profited handsomely from renting their stadiums to the New York Cubans, Newark Eagles, Kansas City Monarchs, Homestead Grays, and Philadelphia Stars. Owners of Oriole Park rented their facilities to the Elites only on limited occasions.

- The city itself was rigidly segregated. Baltimore’s largest employer, Bethlehem Steel, offered only menial jobs to African Americans. The same was true with insurance companies, police and fire departments, hotels, department stores, city government, and newspapers. Most blacks lived in segregated, dilapidated housing. Their children attended overcrowded, poorly financed schools.

- By major league standards, the Elite Giants fared poorly. Players constantly coped with anti-black attitudes from whites and tight budgets. They traveled from city to city in rickety buses without air-conditioning, often overnight without changing out of their uniforms; played two and sometimes three games on back-to-back days; ate sandwiches on the bus slipped to them through the back doors of restaurants, stayed at second rate, segregated hotels, and had someone retrieve foul balls hit into the stands so they could be re-used.

- Even so, many players enjoyed themselves. At $60.00 a month for rookies and $300-to $400 for stars like Roy Campanella, Junior Gilliam, Leon Day, and Joe Black, Elite players made more money than they could elsewhere. They traveled to cities they’d only heard of. Their fans revered them. James “Red” Moore, who held down first base for the Elites from 1939-1940 said, “It was the greatest thing that ever happened to me. We didn’t make too much money, but we travelled around and made some money. My dad liked to be talking about his son.” Hall of Famer Leon Day who pitched for Elites during the 1949 and 1950 seasons said “we were a good bunch of guys travelling down the highway. One guy would start telling lies. Then another. Then we’d start singing ‘Sweet Adeline.’ Play cards. Play some gin rummy. Get to the ballpark, play the game, and get right back on the bus.”

- Others were angry. First baseman Clinton “Butch” McCord, looking back on his time with the Elite Giants (1948-1950), said, “We were in the slave market back then. It took me fifteen years to get over the hurt of not making it to the majors.” Pitcher Joe Black, who did make it to the majors, said when he was with the Elites (1945-1950), “I hated white people. I’m an American and I couldn’t play baseball, the No. 1 pastime.”

- The majors finally did admit African-American players; too late for McCord, Day, and Moore but in time for Campanella, Gilliam, and Black. However, the joy of seeing blacks in major league uniforms was tempered by the demise of the Negro leagues. The majors drained the teams of their best players. The teams folded one by one. By the mid-1950’s the Negro leagues were mostly a memory.

- Integration did not benefit all African Americans in the city. As Brown v. The Board of Education in 1954 and civil rights legislation in the mid-1960’s made segregation and discrimination illegal in schools, at work, and in neighborhoods, many African American professionals moved from the city to the suburbs. Those who stayed in Baltimore no longer had access to the most talented teachers, doctors, morticians, lawyers, dentists, and entrepreneurs. Once vibrant neighborhoods gave way to overcrowding, increased unemployment and crime.

Since this book appeared, the literature on Negro league players and teams continues to grow. Two books I’ve read recently are biographies of two Hall of Fame white men—Bill Veeck, longtime major league executive, and player and manager Leo Durocher. Both were talented, larger than life, and characters in their own right, and both were instrumental in opening the major leagues’ doors to African American players.

Bob Luke is the author of Dean of Umpires: The Biography of Bill McGowan, 1896–1954 and The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues and the coauthor of Soldiering for Freedom: How the Union Army Recruited, Trained, and Deployed the U.S. Colored Troops. His book The Baltimore Elite Giants: Sport and Society in the Age of Negro League Baseball is now available in paperback.

Sources:

Dickson, Paul. Bill Veeck: Baseball’s Greatest Maverick. Walker & Co. New York. 2012.

Dickson, Paul. Leo Durocher: Baseball’s Prodigal Son. Bloomsbury. New York. 2017.