Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Could the famed B&O Railroad be saved? In 1858, one man thought it could.

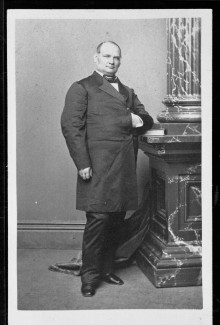

A few blocks away from Baltimore’s lively Inner Harbor stands one of railroading’s most iconic buildings: the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Roundhouse, known as the “Birthplace of American Railroading” and now the home of the B&O Railroad Museum. Built in 1884, this historic building celebrates not only the country’s first railroad, but also the man who commissioned it: John W. Garrett, seventh president of the B&O from 1858-1884.

A full biography of Garrett was long overdue. After writing a biography of his daughter, Mary Elizabeth Garrett: Society and Philanthropy in the Gilded Age, I thought it was time to turn my attention to Garrett. Father and daughter had a very powerful, complex relationship; they greatly influenced and admired each

Elected president when the 30-year-old company was teetering on bankruptcy, Garrett rescued the B&O and led it through its most expansive and tumultuous years, including the Civil War. During the four-year conflict, the strategically located B&O became integral to the Union in providing troop and supply movements to critical battles and also served as the main railroad defense and supply line to Washington, D.C. Garrett became a valued confidante to President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. By the end of the war, the B&O earned the well-deserved status as “Mr. Lincoln’s Road” for its important contributions in the Union’s victory over the Confederacy.

After the war, Garrett took his place among the first generation of the omnipotent Gilded Age tycoons. His Civil War railroading experience provided good training for the fierce postwar competition with other industrial giants: J. Edgar Thomson and Thomas Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad, Cornelius Vanderbilt of the New York Central system, Daniel Drew of the Erie Railroad and financiers Jay Gould and James Fisk. When Garrett took over the B&O presidency in 1858, the line extended from Baltimore to two points on the Ohio River. By the time of his death 26 years later, he had extended the reach of the B&O to the important commercial markets of Pittsburgh, Chicago, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and New York, as well as two rail lines on either side of the Virginia mountains reaching southward to the North Carolina border.

To jumpstart Baltimore’s moribund postwar economy, Garrett initiated the successful Bremen to Baltimore steamship line that brought thousands of European immigrants to Baltimore and transported them on B&O trains to points farther west in the growing nation. He transformed the small prewar Locust Point wharf on Baltimore’s harbor into a giant transportation hub, where B&O hoppers brought tons of coal from the mountains and ships from around the world unloaded their valuable cargo to be carried on B&O trains across the country.

Garrett envisioned bringing prosperity to the B&O and Maryland beyond railroad and steamship lines. He opened the state’s westernmost mountain region to tourism and built opulent hotels where B&O trains could transport tourists from the East Coast and the Midwest. In 1872 the region was named Garrett County in his honor. He supported a range of philanthropic institutions in Baltimore, notably the Peabody Institute, the Baltimore Zoo, orphanages and almshouses. He built Baltimore’s YMCA building, the first in the country, and started the B&O Employees Relief Fund, which became the charitable model for railroad employees. He was instrumental in guiding his longtime friend, Baltimore financier Johns Hopkins, in creating a university and a hospital.

Like most Gilded Age industrialists, Garrett lived large. He owned several lavish homes, including a 1500-acre estate, where he raised 150 prize-winning thoroughbred horses and other valuable livestock. Andrew Carnegie noted that Garrett “was one of the few Americans who lived the life of a country gentleman.” When Garrett died at age 64 in 1884, newspapers around the country heralded his 26-year railroading tenure. “He was a mastermind,” the Philadelphia Press professed. The New York Times concurred, asserting that Garrett was “one of the most prominent men in the financial circles of the country.”

Kathleen Waters Sander teaches history at the University of Maryland University College. She is the author of The Business of Charity: The Woman’s Exchange Movement, 1832–1900, Mary Elizabeth Garrett: Society and Philanthropy in the Gilded Age, and John W. Garrett and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.