Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

Migraine: A History

I didn’t set out to write Migraine: A History as a book spanning nearly two thousand years. As a specialist in nineteenth-century disease and medicine, I’d planned to write something distinctly more modern. In fact, a good friend had gently but firmly warned me off attempting to write a long history early in the project; “You are not Owsei Temkin”, he joked, referring to a magisterial account of the history of epilepsy, first published in 1945.

But I was interested in questions such as who gets to speak with authority about health and illness? Whose knowledge matters enough to be preserved in the historical sources that survive? What kind of history would different kinds of evidence, including images, allow us to write? It proved fascinating to follow the historical threads of a term from its roots in Galen’s second-century term hemicrania, through emigranea in Latin and Middle English and the later vernacular meagrim, to the adoption of the French migraine in the late eighteenth century. I was rapidly drawn further and further back through the centuries.

Of course, all projects develop in ways that cannot be envisaged at the start, but the relatively new (and ever-increasing) availability of digitised material had a profound effect on the shape of the project. Alongside traditional archives such as the casenotes of eminent Victorian neurologists including William Gowers and John Hughlings Jackson, a wealth of material has become knowable and navigable through online catalogues, digitisation projects, and full-text searches. Medical journals, early modern recipe collections, astrological charts, advertisements for pills and potions, letters from wealthy patients to their physicians, even criminal trial records all revealed valuable glimpses of a rich social, cultural and medical history.

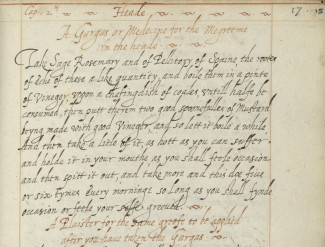

Image: “Medecyne for the Megreeme,” from Mrs. Corlyon’s Booke of Diuers Medecines, 1606. Credit: Wellcome Library.

I was captivated by a diagram of a vein man from the fifteenth-century Guild Book of the Barber Surgeons of York, a practical guide for the medieval physician. One of the twenty bleeding points in the body was identified as good for migraine, its position between the thumb and the forefinger a revealing parallel with a point used in modern-day acupuncture to relieve headache. Then there was Bartholomaeus Anglicus’ thirteenth-century description of beating hammers, a sense of sound, talking or light being unbearable, and a feeling of pricking, burning and ringing. How could such a precise, evocative account of migraine not speak across the centuries?

As I began to consider the potential shape of the book, it became increasingly clear to me that a longue durée approach to revealing the lived experience of migraine was not only possible, but vital.

This is because one of the key issues in modern migraine medicine is a situation the sociologist Joanna Kempner has termed migraine’s “legitimacy deficit”; despite being undeniably a real disease that affects around one in seven of the world’s population, migraine has a credibility problem. It is globally under-funded, under-diagnosed and under-treated. This situation has a history; in the eighteenth century, migraine came to be associated with nervousness, hysteria, and effeminacy, and began to be mocked, rather than taken seriously. By the nineteenth century, physicians talked of migraine as the affliction of female “martyrs”, of mothers whose minds and bodies were weakened by childbearing, exhaustion, and anxiety. These narratives and assumptions about gender have been, and remain, central to the dismissal of migraine. And yet, as my book makes clear, such a situation has by no means been a constant historical fact. In fact, a great deal of evidence suggests that previously migraine had been taken seriously for hundreds, if not thousands of years.

It would be easy for us to dismiss the substance of old medicines - the bleeding points, the worm paste plasters, the reliance on herbal preparations. But those are all part of a very long history. This history has shaped our knowledge about the disease, our changing attitudes towards people who have migraine, and the measures we take to address pain. By comprehending the logic of historical ideas and practices - especially when they seem alien to us - such a long history reminds us that our own knowledge is ever-changing and, most importantly of all, it can and will be bettered.

Katherine Foxhall is a social and medical historian who earned her PhD from the University of Warwick. She is the author of Migraine: A History and Health, Medicine, and the Sea: Australian Voyages c. 1815–1860.