Johns Hopkins UniversityEst. 1876

America’s First Research University

A Palace of One’s Own: Celebrating Professor Richard Macksey

Photo credit: homewoodphoto.jhu.edu

Johns Hopkins and the greater academic community lost a brilliant mind earlier this month when Richard Macksey died. Professor Macksey was an author and journal editor, long-time friend of the Press, and permanent fixture of our Faculty Editorial Board. Over the time I have lived in Baltimore, Professor Macksey also became for me an informal teacher, loyal friend, and trusted mentor. Much has already been written about his legacy as the man who introduced Jacques Derrida and Structuralist critique to America, as founder of the Humanities Center at Hopkins, and as that professor who held seminars in his sizable home.

Mention Dick in conversation and the response is about how he was an institution in the community, that he was as much a part of Hopkins as Daniel Coit Gilman himself. People remember his generosity, his love of conversation, and his passion for books. Invariably, it was this passion that caught people’s attention.

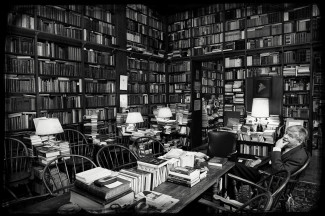

Dick had the largest personal library I have ever seen. Books occupied every available space in his home. Shelves reached to the high ceilings, accessible by ladders. Books lined the windowsills and edged up the wide staircases. To the first question people would inevitably ask, he’d say modestly, “I think about 70,000 volumes” (I am sure an underestimate). The second question was always a trap he saw coming, “Have you read them all?” to which he would say with a sly smile, “no quite yet, but I’m working on it.”

What was so dazzling about Dick’s library is how it reflected the expansive intellect and wild curiosity of its owner. It was a collection that spanned human thought from the earliest times to the present. In fact, it was hard to name a book that could not be retrieved from the house’s labyrinthine shelves. Dick had organized it mostly in broad categories, but he could find any book within seconds. This was no precious collection, although it contained countless exceedingly rare and one-of-a-kind books. No, Dick saw books as tools. They were meant to be read from, taught from, and argued with. As we talked alone in front of the fire, I often felt that Henry James and Marianne Moore and Cicero were there among us for the party.

I came to realize that this library was part of Dick’s own mind. It was expansive, interconnected, and had secret passages that linked disparate ideas from entirely different fields. You’d think the library was mostly literary, but it included impressive rooms filled with works on early science, philosophy, and history, baseball and vintage comics, forensics, Chinese pottery, and works in many languages. He once showed me a Sanskrit volume handwritten in human blood: “You know, Greg, all great writers must work this way.”

Memory experts talk about the mind as a place where specific ideas can be stored for quick retrieval. For ancient Greeks and Romans, it was the method of loci: recall the imagined room and you’ll remember the idea. Sherlock Holmes would say the mind was his attic, a place where he could store infinite mental observations. For Dick, his library was his memory palace, vast and inviting, and he would share it with anyone with who showed a spark of curiosity.

The night after he died, I walked over to his house, a big, hulking place in the better part of town. It was closed up tight with the curtains drawn, but I imagined him flinging open the door in a curl of pipe smoke, smiling with one book in hand and another under his arm. No such luck that summer night, and never again. As I walked away, I took one last look back. There was a single light in the attic burning brightly.

Greg Britton is the Editorial Director at Johns Hopkins University Press, and a long-time friend of Professor Richard Macksey. You can follow him on Twitter at @gmbritton.